In this three-part series from The Behavioural Architects, we look at a strategic approach to understanding and setting expectations for the impact of nudging. This series of articles aims to help you apply behavioural change interventions - nudges - more effectively, using a simple two-step strategic framework that helps set clear expectations of the potential impact of any nudge. Part one outlines the most common misunderstandings around nudging and sets out the need for a framework.

Nudging has become widely recognised and adopted

The central, highly attractive proposition at the heart of nudging is that with small, low cost tweaks and adjustments in environment or communications, behaviour can be altered, hopefully for the better. This simple promise, driven by behavioural science, has meant that, in little more than a decade, ‘nudging’ has taken root in governments and organisations around the world. There are now over 200 public institutions applying behavioural insights to their policies and a recent survey found that there are more than 800 behavioural science teams around the world, and this is likely an underestimate. After over 15 years in the mainstream it is a good time to reflect on the application of behavioural science.

Its popularity has brought some misunderstandings and misuse

A common misunderstanding is thinking of a nudge as binary - it works or it doesn’t. In reality, it has become clear that not all nudges are equal and we need to think more strategically about this.

- First, popular books have often made nudges feel overly simple to apply. There is a temptation to rush to action which can often lead to disappointment and the wrong conclusions around effectiveness. It is vital to take time to understand the context which we seek to influence or change; whilst also acknowledging what people are doing or not doing already, and why. Neela Saldhana, behavioural scientist and Executive Director at Yale University’s Research Initiative on Innovation and Scale, notes the immense task of applied behavioural science in different contexts together with the importance of fully understanding cultural influences before designing any intervention. She says:

“Behavioural interventions seem so simple when you read the books. The biggest lesson I learned was how hard it was to apply even simple interventions when they have not been tried out in a particular context. You have to understand the culture deeply before you can think about working towards behaviour change solutions.”

The beauty of behavioural science lies in the understanding, and in the action this understanding inspires.

- Second, we all know that context is king in behavioural science, yet when applying nudges, people may often overlook what can be controlled or changed. The extent of impact from a nudge may be limited by what we can control, or what is possible for us to change in a given context. More often than not, the context drives what you can do.

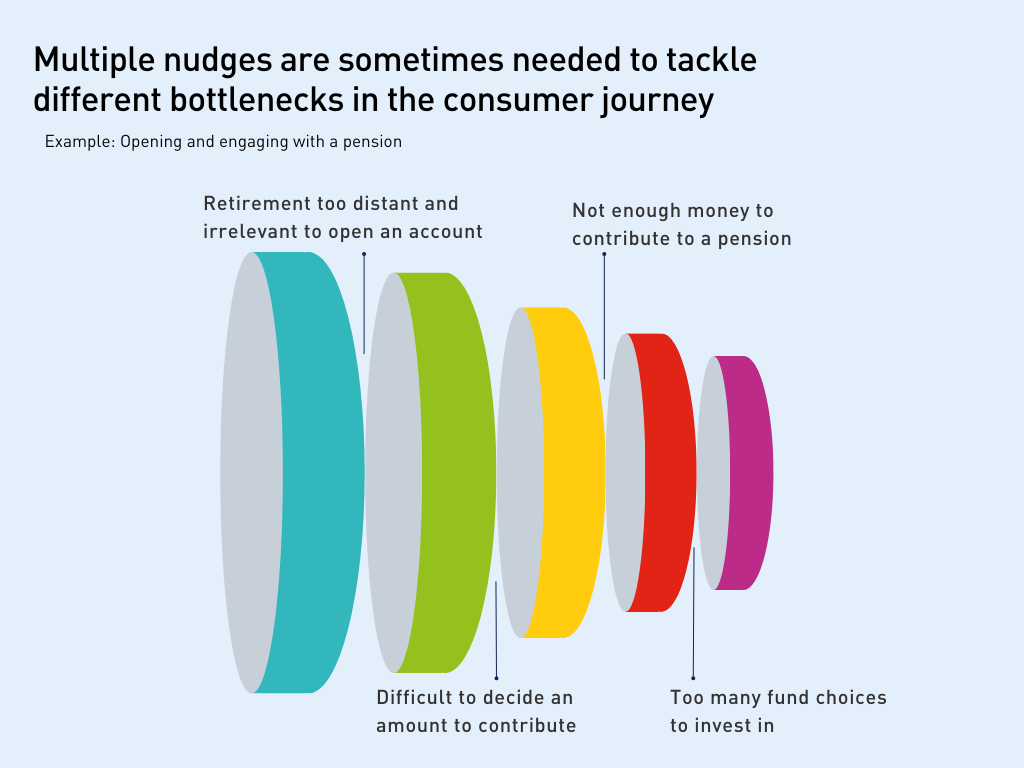

- Third, we’ve seen many blinkered approaches in which clients and practitioners test only a single nudge when research has shown more significant success can often come from cumulative marginal gains, perhaps better described as a ripple of interconnected nudges applied throughout the entire consumer journey. Behavioural scientist Dilip Soman notes there may be a number of bottlenecks throughout the consumer journey leading to drop-out. Nudging at only one of the bottlenecks may not be enough for success; ideally, all the bottlenecks need addressing. There is a need to understand how nudges can interact, in combination with one another. The collective whole is often greater than the sum of its parts.

- Last, and perhaps most significantly, ‘nudge’ has become a wraparound term for leveraging myriad cognitive biases in the brain and, as a result, the considerable impact of nuance can be lost. We know that some nudges have the potential for eye opening impacts - changing the default option for example; others, like how we frame information, or make known what someone’s close peers are doing, are likely to have more nuanced or varied impacts. This variance can define what level of behavioural change we can reasonably expect.

Taking this as our context we have developed a strategic framework for setting expectations for nudging and behavioural change interventions

Each of the points above lays out the need for a strategic framework for nudging, a framework based on 12 years of working in applied behavioural science and seeing the same misunderstandings and mis-practices occur again and again.

In part two we will look at the need to acknowledge that not all nudges are equal; and how impacts can be marginal as well as major. We look at what we know so far across the evidence base and examine variance in nudges across a range of contexts.

In part three we present a simple two-step strategic framework to help you assess any context in order to define the opportunity and manage expectations. We then outline how to optimise behavioural science concepts based on your existing deep contextual understanding.

Part two of our series will be published on 30/10/23

Written by Crawford Hollingworth, Liz Barker and Lucy Pilling - The Behavioural Architects