Two years of a global pandemic, followed by soaring inflation and the start of a recession means we find ourselves constantly having to change and adapt our behaviour. In the new normal, boring and stable have become aspirational!

The New Year is inevitably accompanied by the desire or motivation to cease or initiate certain behaviours. But we all know how quickly good intentions can fall by the wayside. Behavioural science tells us that one key reason we fail is because we don’t take context into account - the circumstances and setting in which our behaviour occurs and the types of cues and reminders we use to prompt us to enact a behaviour.

Taking this thought even further, BeSci has shown us that not all cues are equal. In this article, we highlight recent research findings which identify what it is about a cue that makes it most likely to be successful and, conversely, what distinguishes unsuccessful cues. We also weigh up the implications for researchers and behavioural change practitioners. These findings highlight how having a clearer understanding of effective and ineffective cues could inform future behaviour change interventions; helping people to select cues that best fit their context and so ensure a strong habit is built. And to ensure those of us with New Year resolutions have more success!

The Science of Habits

It’s well established that building cues - background reminders in your surroundings which automatically make you think ‘Aah, I need to do x or y’ - can be an effective way to build a new habit or routine.

When we consistently perform a behaviour upon encountering a specific cue in our context, it reinforces the association we have between that cue and the behaviour. For example, we pick up our keys to leave home and the keys remind us to lock the front door; or we switch on the kettle which prompts us to reach for a mug and a teabag; or we hear a particular alert on our phone and immediately check a certain app.

As these associations strengthen, the behaviour happens more and more automatically and habitually as our control over the new behaviour shifts from the conscious, intentional and memory-based parts of the brain to non-conscious parts of the brain, where a behaviour is triggered by our surrounding context.

Exploring effective habit cues/Not all cues are equal

It is clear that some types of cues seem to be more effective than others at prompting a behaviour. Qualitative research by science of habits experts Katarzyna Stawarz and Ben Gardner, psychologists at the Universities of Cardiff and Surrey respectively, explored what makes an effective strategy for cueing simple habits. Previous research by Gardner on establishing habits has already found that, left to their own devices, people often pick sub-optimal cues. One of the questions he had sought to answer was what it is about sub-optimal cues which made them unsuccessful? The main factors turned out to be the lack of a stable context, failing to specify a time slot in the daily routine and choosing only one cue.

In this new work, Stawarz and Gardner explored how, with no guidance, people worked out for themselves how to remember to take a daily vitamin C tablet and build a new habit. They recruited 38 young people - who have often not formed any pill-taking habits - to make taking a daily vitamin C tablet a habit over the course of three weeks. Crucially, they were given no guidance, leaving them to work out how to remind themselves.

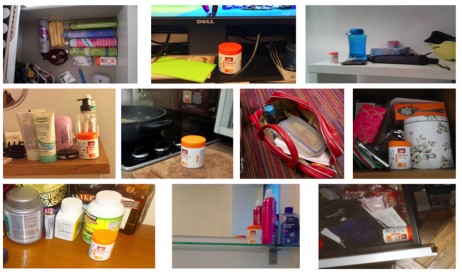

The research explored how people responded through a combination of in-depth and semi-structured interviews, one at the start and another at the end of the study; and two evidence-based structured questionnaires (one to measure memory ability and another to measure the strength of habit), together with in-context photo submissions of where participants were keeping their tablets. Adherence was primarily determined based on participants’ self-reports of forgetting.

Most participants took their tablets roughly the equivalent of 5 times per week, or 71% of the time. Scores from the questionnaire measuring strength of habits, taken at the end of the 3-week period, showed a weak habit had started to form for 11 of the participants.

The final interview focused on participants’ experience of attempting to take vitamin C tablets, including remembering strategies; their rationale for selecting specific cues; the ease of remembering; the reasons for forgetting, the role of visual cues; problems with existing automatic behaviours; and the differences between initial plans for remembering vitamins and the actual strategies used.

Good cues and bad cues

The research identified some common simple flaws in how people approached the task, such as choosing strategies they had used before, regardless of whether they had worked or not, and having very vague plans. Many experimented with a whole wealth of cues, using trial and error to explore what worked best for them, and this tended to take a couple of weeks. Many participants used multiple cues; keeping the tablets in a specific location (by their bed or on their desk were common) and piggybacking taking the tablet with an existing routine, giving them a specific time cue as well, for example, after morning coffee or brushing teeth, or after other medications they were already taking.

Gardner and Stawarz’s analysis enables us to identify a strategy for building optimal cues for a new habit:

- Choose multiple cues: Choosing only one cue - whether it was a location, routine or object - proved to be a weak strategy, and meant people were vulnerable to forgetting. For example, one participant placed her tablets in her bag with her laptop charger but found that on some days she was so busy she didn’t take the charger out of her bag. Participants who relied on multiple cues tended to be more successful at remembering.

- Pick a stable context: Participants who led stable lives and who picked a stable context which they were likely to encounter virtually every day had more success taking their vitamin tablet. Those who chose unstable contexts which could change from day to day had less success. For example, one participant chose to keep their vitamins in their jacket pocket thinking they would be reminded to take the tablet when they heard the rattle of the bottle as they walked, but failed to forecast how fragile this strategy might be if they chose to wear a different jacket, or if the weather changed, or if they didn’t leave the house.

- Specify a narrow time slot: Participants tended to have less success when they didn’t specify a rough time slot in their daily routine, relying on a vague strategy of I’ll take it when I see it. The problem with this is that we adapt to visual salience; we get used to what’s in our vicinity and gradually stop noticing things. Not only did this mean they sometimes forgot to take it, but that oftentimes they couldn’t remember if they had already taken it or not: “I would walk around my room and it would catch my eye and I would be like ‘did I take it or not?” In contrast, participants who picked narrower, more specific time slots such as ‘after morning coffee’ or ‘after alarm clock’ tended to do better.

- Piggyback to an existing routine: Many participants who were successful tended to tag it onto an existing routine such as taking it with their contraceptive pill or after brushing their teeth. This is born out in previous research. Consumer research shows that connecting the new habit to a connected routine can make for a very strong habit cue. For example, flossing after brushing teeth, or doing physio exercises after a run or a gym session.

So, to successfully build a new 2023 habit and to make it last beyond the second week in January, make sure; there are multiple cues to fall back on, pick a stable location, narrow down a specific time slot and, if possible, piggyback the new habit to an existing one. Make the cues as specific and unique as possible for successful behaviour change.

Implications

- For researchers, in-depth qualitative research like this really helps us understand why we need to research cues and how we might analyse habitual behaviours or the failure to develop a strong habit.

- For behaviour change practitioners, it gives us powerful insights into how we might help people develop stronger daily habits; building a clear strategy for how to design and leverage the right cues most likely to have success, and helping people to create their own personalised action plan.