As behavioural science has evolved, new questions have arisen about how behavioural traits and cognitive biases vary between individuals, even within narrow samples of society.

In this, our 11th article on the new frontiers of behavioural science, we explore how individual contextual factors can influence a person’s behaviour and in turn provide new opportunities to nudge in a more nuanced and tailored way. Whilst blanket or one-size-fits-all nudges can often be the best choice in a given context, personalising and targeting interventions to appeal to individual traits can also be beneficial when it is possible and practical to do so.

Behavioural traits and cognitive biases vary within populations

There are growing new findings that our behavioural tendencies can significantly differ depending on a number of individual factors. In the last few years it’s become more evident that people’s decisions and behaviours, and the degree to which they experience cognitive bias, can vary according to their genetics, age, experience and more. Behavioural economist Koen Smets reminds us that cognitive biases are only “broad tendencies, which are not uniformly shared by everyone. We are not all equally likely to respond to, say, social proof: some of us tend to be more conformist; others are more the rebellious kind.”

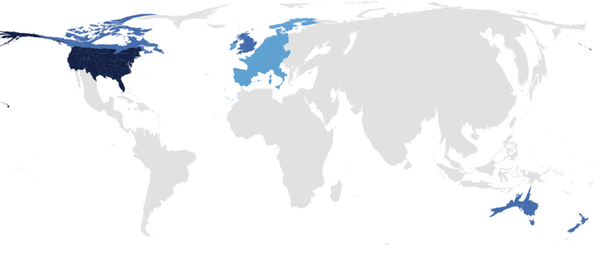

Also, over the years, researchers and practitioners have sometimes overgeneralised, assuming findings about the behavioural traits and cognitive biases from one small population can be extrapolated to all others. Often they can be, but not always. Much of the research from behavioural science and psychology, but also neuroscience and other disciplines has largely been conducted on a rather narrow slice of humanity - often labelled 'WWEIRD' (White, western, educated, and from industrialised, rich, and democratic countries). This was an outcome of a rather different research world to the one we know today, a pre-internet age where it was much harder to gain research access to diverse populations. The most easily available sample of people available to researchers in the 1970s, 80s and 90s, and even today has tended to be the psychology undergraduate (see Figure 1 below).

Analysis of top journals in six sub-disciplines of psychology between 2003-2007 found that 68% of study participants came from the U.S. and 96% were from Western industrialised countries. This means that 96% of participant samples were drawn from just 12% of the world’s population. Moreover, for one of psychology’s top journals, 67% of the US samples and 80% of samples from other countries comprised of undergraduate psychology students. In addition, most research is carried out on white participants and there are few studies carried out with Hispanics despite them making up 18% of the US population. It seems reasonable to deduce that the behavioural traits of an Indian construction worker or a Japanese business woman might be somewhat different to a white American psychology undergraduate. As researchers Joseph Heinrich and colleagues emphasise, the existing participant base “does not reflect the full breadth of human diversity”. In fact, his research even suggests that some western behaviours fall at the more extreme end of the spectrum!

Figure 1: Blue countries represent the locations of 93 percent of studies published in Psychological Science in 2017. Dark blue is U.S., blue is Anglophone colonies with a European descent majority, light blue is western Europe. Regions sized by population. Source: The Conversation 2018 and Rad, M.S., Martingano, A.J., Ginges, J., ‘Toward a psychology of Homo sapiens: Making psychological science more representative of the human population’ PNAS November 6, 2018 115 (45) 11401-11405

This opens up a huge opportunity for researchers to explore a wider pool of humanity and better understand these individual variations.

Practitioners can face a slightly different situation or scenario. Often, a simple, general nudge for a single population can be beneficial. ‘One-size-fits-all nudging’ or ‘blanket’ nudges can generate a useful uplift and valuable change in the behaviour of a significant proportion of people whilst also being economical and quick to implement. Some behavioural interventions also require the scale to achieve effectiveness, for example public promises or social norm interventions. However, depending on the behavioural challenge, it might be the case that – where possible - implementing more targeted nudges, tailored to specific types of individuals, cultures or contexts may have even more impact .

Furthermore, it’s important to consider the equity implications of ‘one-size-fits-all’ interventions that aim to target the average person. Rehka Balu at the Center for Applied Behavioral Science (CABS) says “A behavioral intervention that reduces hassle factors on average could be experienced by some groups as an increased burden. Nudges […] might prioritize individuals who already have relatively higher resources and need only a small push to get them to the finish line. If we don’t design for the needs of specific races, ethnicities, social classes, genders, and sexual orientations, are we increasing inequality in outcomes? … At an individual level, this may involve more differentiated and personalized interventions. ” So, there may be situations where there is a moral and ethical responsibility to develop tailored nudges to target those in most need of behavioural change.

Current New Frontier developments today

Increasing sensitivity to broader, more representative, samples and individual differences

Some of the most exciting and valuable research going on today is trying to better understand variation across people and societies. In practical terms, this recognition is changing the way behavioural science research is conducted, crossing a critical threshold and moving away from small-scale lab studies with WWEIRD university students, to conducting research with large samples of participants from broader sections of society across a wider number of countries. We now see a growing number of large-scale field trials, tracking actual behaviours, which are often collaborations between the private or public sector and academia.

For example, trials of PREDICT – a tool to help patients understand treatment options for breast cancer - found that there is no ‘best’ way of visualising the outcomes of each treatment option to patients. Individual preferences and comprehension varies greatly based on a person’s numerical, verbal, or graphical skills and understanding. One size definitely does not fit all. As a result, the research team developed five different displays for communicating the data, improving each one over time based on patient feedback.

Technology and data science have also helped to enable this shift meaning research and interventions can be run at a nationwide or even global level, providing a large and more representative sample at relatively low cost. This is definite progress and in the coming years we will see even more of these types of studies.

Behavioural Science is exploring the following key variables that might lead to individual differences

Below we explore the following five variables / factors:

● Genetics

● Skills and long-term contextual influences

● Culture and societal differences

● Socioeconomic factors

● Age

i) Genetics: Our genes are now believed to influence a significant proportion of our behaviour and choices. Here we focus on one cognitive bias - present bias - to illustrate the amount of individual variation. People certainly have varying abilities to resist the ‘temptation of the now’ for long term rewards. We all know the person who can’t resist chocolate and the other person who, 12 months on from Christmas, hasn’t even opened one selection box. Or the person who procrastinates about their tax return right up until the final deadline versus the person who has completes their accounting each month so the final submission is a doddle.

This is borne out in genetic studies on the heritability of present bias and impulsivity. In a study of over 1,500 identical and fraternal twins and their parents using Sweden’s infamous Twin Registry, researchers Henrik Cronqvist and Stephan Siegel found that savings behaviour was more correlated among identical twins than fraternal and could explain around 35% of savings behaviour. This effect is present over a lifetime and does not lessen as people age. Other research has found that genetics can explain as much as 45-50% of impulsive behaviour.

Further research identifies additional sub-groups for individuals affected by present bias; whilst some people do not have any degree of present bias, and some might be poor at predicting that they will suffer from present bias in a future situation, and continually make impulsive, short-term decisions (known as someone who is ‘naive present biased’), a third group are what we might call ‘sophisticated present biased’ and, having learnt from experience that they are in danger of succumbing to a short-sighted decision in the future - such as pressing snooze on their morning alarm - they set up what are known as ‘commitment devices’ in advance - perhaps putting a second alarm clock across the bedroom, forcing themselves to get out of bed to turn it off. This ability to learn quickly from experience is again thought to be genetic. A 2015 study on savings behaviour by John Beshears and his colleagues suggests some savers are indeed sophisticated and know about their present bias, some show naïve present bias, lacking any awareness of their impulsiveness, whereas others show no evidence of present bias and have no trouble putting money away.

ii) Skills and long-term contextual differences: Behavioural scientists are also finding that not everyone is affected by cognitive bias to the same degree due to learned skills, not necessarily solely genetic.

One example of individual differences is found in the degree to which framing - how information is presented - affects individuals. Framing often involves presenting the upside or downside of a choice in numerical terms, for example a 90% chance of mortality versus a 10% chance of survival. A considerable body of research has found that those who are more numerate - comfortable and proficient in dealing with numbers and statistics - are less influenced by framing effects like this. This may be because less numerate individuals focus less on numerical information which they struggle to understand or find off-putting and instead are more affected by other information such as positive and negative words that elicit the bias, other more emotional information, perhaps from a linked image, or even an individual’s mood at the time. It’s important to note that numeracy is not perfectly correlated with high levels of education or even intelligence. Yes, proficiency with numbers may initially be an individual strength, but it’s also one that needs to be built on and developed to gain high levels of numeracy. So, we can consider numeracy a skill. With the wide variation in numeracy levels in many countries – the impact of framing effects is also likely to vary considerably among individuals.

iii) Culture and societal differences: A significant question among behavioural scientists - and their critics - is how generalisable many of the identified cognitive biases are across cultures. For instance, descriptive social norms - the understanding that we tend to want to conform to what others are already doing - are a frequently applied insight and tool among behavioural scientists. And yet research now suggests that the extent to which people tend to conform varies considerably across different societies and cultures.

For example, a review of studies across 17 varied and different countries found that motivations to conform were weakest in Westernised societies compared to other countries, particularly those in East Asia. Other research has consistently found that on average, Americans tend to be one of the most individualistic societies in the world meaning they are less likely to conform. Research by Heejung Kim and Hazel Rose Markus looking at white Americans and South Koreans found that Koreans tended to prefer products and advertisements themed around the idea of conformity, whereas Americans preferred uniqueness. Within the US, studies have also found that the desire to conform is even weaker among US students than non-college educated participants. Significantly, behavioural interventions applying social norms to change behaviour in some way or other have also had varying success across a range of locations, from Poland to Guatemala to the US.

We need to be asking questions about other cognitive biases too. To what degree does cultural or social background affect our propensity to experience loss aversion, affect bias, or present bias? Particularly if we are considering leveraging it for behaviour change. It could be worthwhile exploring to what degree your target group experience that bias and if it might cause them to change their behaviour.

iv) Socioeconomic factors: where and how we grow up or the characteristics of our adult lifestyle may also affect our behaviour to a significant degree. Neuroscientists have found that chronic stress can affect our ability to make good decisions. Stress hormones have been shown to have a detrimental influence on the pre-frontal cortex, the part of the brain which guides us to make more rational, less emotional decisions, helping to reign in our impulses and plan for the long term. Stress weakens the connections and wiring between neurons in this region, making it harder or slower for them to communicate. On top of that, the region becomes chronically inflamed and the total cell volume is also reduced.

There are multiple implications on cognitive ability from these effects, such as greater likelihood of impulsive decisions and present bias - when we weigh gains in the present more than we do gains in the future. We simply don’t want to wait for a reward.

Scientists have found evidence of this impact not only in adults, but also in children. As their brain is still developing, chronic stress can have long term, permanent impacts. It tends to be found among children from low income / low SES households where stressful or chaotic lifestyles tend to be more common. Research has found that children who grew up experiencing high levels of stress – such as poverty and abuse - not only show poor development of the pre-frontal cortex as a child, but also as an adult, meaning they are more likely to be affected by present bias. As biologist Robert Sapolsky says “Poverty makes the future a less relevant place.”

This finding has wider implications for research too. Much of the previous research on cognitive bias and neuroscience has tended to be conducted on higher income, well-educated groups, given the typical profile of the university undergraduate. The same goes for childhood studies which have also tended to be conducted on children living nearby a university or even attending the university kindergarten. These children tend to be from more affluent and well-educated backgrounds. Researchers have realised that there is a real need to better understand the typical behaviours and neural characteristics of lower socioeconomic groups and widen our understanding of how the context we are brought up in can determine long term behavioural traits.

Keeping the role of socioeconomic background in mind when we consider to what degree people might experience various biases is important. We are not all the same and recognising the influence of factors like how our background and experience has shaped us is valuable to understanding our behaviour today.

v) People’s behavioural traits change depending on their age: We often like to believe our traits and characteristics are unchanging and stable. Today, it’s hard to imagine that in twenty years we might have different preferences and tendencies to those currently defining us. However, scientists are beginning to understand how our tendency to be affected by different cognitive biases changes throughout our life, from childhood to old age. As little as twenty years ago, scientists assumed that most of our brain’s development had been completed by mid-late childhood. With developments in brain imaging technologies, we now know that huge amounts of development and adaptation - remodelling, strengthening some connections whilst pruning others - continue throughout childhood and adolescence. In fact, our brains have not fully developed until we are in our mid-twenties!

Not long after we reach adulthood, some functions in our brain related to what’s known as our fluid intelligence - our reasoning ability and ability to engage in logical problem solving - begin a slow decline. For the most part these declines are offset by our ever-increasing knowledge and experience of the world - known as our crystallised intelligence. Neuroscience research suggests that our brains continue to adapt and change until their forties, and even then, the brain is always plastic - highly adaptable to our surroundings and current context. By our 60s and 70s though, an overall decline in cognitive function is unavoidable which feeds into several other changes in our thinking and decision-making.

This means that the degree to which we are affected by cognitive bias may change throughout our lifetime. For instance, teenagers tend to be more motivated by peer influences than older adults and are likely to be driven by social rewards. There is also evidence that they are more impulsive, particularly in emotionally-charged situations due to incomplete developments in the brain.

At the other end of the spectrum, older people tend to be more drawn towards positive emotional experiences, and positive information as opposed to negative. Younger people – even children and infants – are more drawn to negative information and stimuli. This is perhaps surprising and contrary to the well-known stereotypes but can be explained by the stage older people have reached in life. Gone are the goal striving, purpose-seeking, horizon-expanding days of their youth. Instead they focus on what brings emotional satisfaction, either through meaningful relationships (such as grandchildren or friendships), or ways in which to savor life, perhaps because they perceive their life is nearer its end than its beginning. These findings have clear implications for behavioural science - gain frames and communications with positive affect are likely to be more appealing to older people than loss frames and scare tactics.

Another example is that although older people are still capable of drawing on their fluid intelligence to conduct more ‘System 2-led’ decision-making, it requires more effort as they find it harder to ignore or sift through irrelevant information. Consequently, they tend to be more selective about using System 2, saving their cognitive resources for important decisions and instead relying more on gut-feel, learned rules of thumb and mental shortcuts for less important, inconsequential decisions. As a result, older people also tend to prefer simple choices with minimal options and information that is succinct and straightforward.

The implications of these latest findings suggest that to understand behaviour, we need to understand the nuances between different groups and across individuals. This enhanced understanding grants us the ability to tailor interventions towards different groups such as age-based, cultural or socioeconomic, and to better assess the landscape to decide when a widespread nudge versus a more tailored intervention would be most appropriate.

The Future

In the coming years, more research to understand various group-based and even individual variations in behavioural tendencies will be welcomed. We have already learnt a lot, but more will undoubtedly be useful, particularly for designing more targeted behaviour change interventions.

Technology and data science are already helping practitioners to do the latter more effectively, even if the underlying mechanisms explaining the variation in people’s behaviour are not yet always fully understood or explainable. In particular, machine learning is enabling us to identify patterns and clusters in data, typically huge sets of data, crucially with no prior knowledge of what those patterns – such as behaviours or similar characteristics - might be. These are often patterns the human eye isn’t able to spot; and will enable practitioners to more specifically target behaviour change interventions according to the unique segments, clusters and patterns of identified behaviour.

For example, a recent trial to reduce fraudulent claims of unemployment benefit illustrates how machine learning can help to more accurately target behavioural change interventions to only the relevant sub-set of individuals. Behavioural scientists from Harvard University together with data scientists from Deloitte collaborated with the New Mexico state government to try to reduce numbers of dishonest unemployment claims. The state pays $2 billion in overpayments so it is a significant problem. Once registered as unemployed, claimants are required to confirm their status each week, answering the question “Did you work during the reporting period listed above?”

By using machine learning to analyse the data of over 51,000 claimants they were able to predict with 77% accuracy which individuals were likely to commit fraud. The algorithm drew on 300 data points about an individual - not only historical and habitual data but also real-time contextual data which individuals were revealing on the claimant platform. For example, a significant predictor of a fraudulent claim was if an individual changed the time of day or week that they usually made their weekly claim. This predictive capability enabled the team to target only those most likely to commit fraud with nudge messages to deter and ultimately reduce fraudulent behaviour.

In conclusion:

Better understanding of subgroup and individual variations in behavioural traits is certainly one of the next missions of behavioural science. It could also be the golden ticket to designing more tailored behavioural change interventions, arming us with the ability to design nudges that range from widespread to more targeted, depending on the behavioural challenge at hand. The future for applied behavioural science lies in having a much greater ability to assess the behavioural landscape and choose at what level we should customise interventions, ultimately designing more effective behavioural nudges.

Why it Matters

Obtaining a better understanding of subgroup and individual variations in behavioural traits is undoubtably one of the next missions within the behavioural science field, made possible through more representative and diverse research. As a result, the future for applied behavioural science lies in identifying the appropriate level of customisation and rise of ‘bespoke’ interventions, ultimately achieving more effective behavior change.

Key Takeaways

- There is a growing body of evidence that suggests that our behavioural tendencies – our behaviours, decision making, the degree to which we experience cognitive biases - can significantly differ depending on a number of individual factors.

- We are learning more and more about these differences due to more diverse – and representative – samples from different populations and subpopulations.

- There are a few key characteristics that have been found to influence behaviour in varying ways, specifically: genetics, skills and long-term contextual influences, culture and societal differences, socioeconomic factors and age

- As a result of this growing depth and nuance in new research, we will be able to design more targeted and customised behavior change interventions, where deemed appropriate. Technology and data science are already beginning to spur this development.

New Frontiers in Behavioural Science Series:

Article 1 - The Past, The Present and The Future

Article 2 - Default Settings - The most powerful tool in the behavioural scientist's toolbox

Article 3 - Social norms and conformity part 1

Article 4 - Social norms and conformity part 2

Article 5 - System 1 and System 2 thinking

Article 6 - When is choice a paradox?

Article 7 - Beyond mugs and wine

About the authors:

Crawford Hollingworth is co-Founder of The Behavioural Architects, which he launched in 2011 with co-Founders Sian Davies and Sarah Davies. He was also founder of HeadlightVision in London and New York, a behavioural trends research consultancy. HeadlightVision was acquired by WPP in 2003. He has written and spoken widely on the subject of behavioural economics for various institutions and publications, including the Market Research Society, Marketing Society, Market Leader, Aura, AQR, London Business School and Impact magazine. Crawford is a Fellow of The Marketing Society and Royal Society of Arts.

Liz Barker is Global Head of BE Intelligence & Networks at The Behavioural Architects, advancing the application of behavioural science by bridging the worlds of academia and business. Her background is in Economics, particularly the application of behavioural economics across a wide range of fields, from global business and finance to international development. Liz has a BA and MSc in Economics from Cambridge and Oxford.