“A wine-loving economist we know purchased some nice Bordeaux wines years ago at low prices. The wines have greatly appreciated in value, so that a bottle that cost only $10 when purchased would now fetch $200 at auction. This economist now drinks some of this wine occasionally, but would neither be willing to sell the wine at the auction price nor buy an additional bottle at that price.”[1]

Introduction

The story above is an example of endowment effect: someone who owns a good will value it more than someone who does not. Behavioural economist Richard Thaler coined the term in 1980, having noticed many anecdotal anomalies such as the one above in his everyday life. Together with Daniel Kahneman and Jack Knetsch, he later demonstrated how widespread the phenomenon was in research such as the well-known study asking students to buy and sell Cornell University mugs.

In this article, the fifth in our series on the new frontiers of behavioural science, we look at the endowment effect more closely - specifically analysing two areas:

- Originally, psychologists thought the mechanism behind endowment was caused by the concept of loss aversion - when we feel the pain of a loss more than the pleasure of a comparable gain, combined with feelings of inertia - when we stick with what we have already or with the status quo. However, new research now suggests that there may be other explanations at play.

- Secondly, we look at what factors seem to strengthen or weaken the effect. Do we always experience the endowment effect or does the context matter?

Where we were

You’re probably already familiar with what’s become known among behavioural scientists as ‘the mug study’. Published in 1990, Thaler, Kahneman and Knetsch demonstrated that people tend to ask greater prices for goods that they already own than they are willing to pay for identical goods that they do not own.

They carried out the study on students at Cornell University. Half were given Cornell University coffee mugs. Half were not. These mugs were on sale for $6 in the university shop. When asked how much they would be willing to sell or buy a mug for, students given mugs did not want to sell them for less than $5.25 on average, compared to students without mugs who were only prepared to buy them for between $2.25 and $2.75 on average. Thaler and his colleagues argued that this phenomenon could be explained using the concept of loss aversion, commenting that “‘the main effect of endowment is not to enhance the appeal of the good one owns, only the pain of giving it up”. Additionally, they believed our tendency to experience inertia and prefer the status quo also helped to drive the effect; once we own an item, we’d prefer to keep it. If we don’t own it though, we see no need to acquire it.[2]

Current developments

i) Mechanisms behind endowment effect

Since the mug study other researchers have explored a number of other plausible psychological mechanisms beyond loss aversion and inertia to explain the endowment effect. For example, it may be caused by feelings of psychological ownership and possession rather than loss aversion. Research in 2009 by Carey Morewedge, Dan Gilbert, Timothy Wilson and Lisa Shu showed that the endowment effect can be present simply through owning an item. For example, they found that people who were given a coffee mug were willing to pay as much to buy an identical second mug as they demanded to sell the first mug they were given.[3]

Simply owning an item may cause someone to rate it more positively and see lots of good things about it as opposed to those who don’t own it. Even merely touching the item or touching an image of the item or imagining owning it can generate a more positive evaluation if such actions create feelings of psychological ownership. For example, research recently conducted by Adam Brasel and James Gips found that using a touchscreen to choose a product or service increased both people’s sense of psychological ownership and willingness to pay, particularly more haptic products. The effect also strengthened when the touchscreen device – an iPad – was owned by the participant as opposed to the university laboratory. Brasel and Gips believe that if people owned the device it contributed to feelings of endowment and ownership of the product they were browsing and exploring.[4]

It’s thought that the ownership effect could be driven via two different processes:

- The first relates to the idea that owning an item leads to it becoming part of the owner’s identity, finding attributes which relate to the owner’s concept of their self and meaning that they perceive the potential loss of the item as a threat to their self. For example, the owner of a classic car might feel the car is a fundamental part of their identity, and a loss - perhaps a theft - of the car may feel like losing part of their self.

- The second process relates to developing a stronger memory of the owned item, making it easier to recall its positive features and consequently see greater value in it. Neuroscientific research supports this theory; one study found that imagining ownership of an item activated a region of the brain involved in self-referential memory and subsequently led to more positive evaluations of the item. This contrasted with evaluations from those who were asked to imagine someone else owned the item.[5]

Another potential driver behind the endowment effect is a type of cognitive framing effect, where owners and buyers consider different information about the item when evaluating a good. More specifically, positive and negative qualities of the item may be more or less salient to someone, depending on whether they are potentially buying or selling it, or own or don’t own it. If we already own an item, we are likely to notice and more easily identify or bring to mind positive attributes of the item. However, if we don’t own the item, it may be easier to spot and bring to mind negative features. This effect may in turn both strengthen feelings of ownership and make us more reluctant to sell. For example, if we can easily bring to mind attributes that suggest we should keep hold of the item or buy the item, it should increase in value - and vice versa.[6]

Carey Morewedge, who has researched this type of framing mechanism behind the endowment effect, discusses the mechanism with an example, below:

“...owning a thing changes the way we think about it. Most of us exhibit a memory bias for things related to ourselves. We tend to pay more attention to and better remember information that is associated with us than other people, places, or facts. [...] Buyers focus on reasons to keep their money and reasons not to buy. Sellers focus on reasons to keep the item and reasons not to take the money. When buying a ticket to a sold-out basketball game, we might think about the hassle of getting there and what else we could do with the money. By contrast, when selling we might think about how much we paid for the ticket and the quality of the game.”[7]

ii) What factors strengthen or weaken the endowment effect?

The varied explanations for endowment effect outlined above also imply that people might experience it to stronger or lesser degrees depending on the exact context they are in.

For example, it’s probably no surprise that research has found that people who possess a good for a longer time typically value it more.[8] The endowment effect is also stronger if someone physically owns something, as opposed to mere legal ownership.[9] Holding something you own in your hands or being in it (such as a house or car) is very different to there being an official document somewhere saying that you own it.

Researchers have also found that anticipation of ownership - perhaps a house purchase that is waiting to go through, or something you’ve ordered online but still needs to be delivered - can strengthen the endowment effect. People who may anticipate owning a good in the future value it more than people who do not expect to acquire that good.

Similarly, people who expect or intend to trade an item they own show little or no endowment effect, perhaps because it makes them more accepting of a future loss, or that they never fully feel a sense of ownership. For example, experienced traders are less likely to suffer from endowment effect. Behavioural economist John List conducted an experiment in 2003 with real-life collectors - from novices to experienced collectors - who trade baseball pins and sports cards. In exchange for completing a survey, each trader received either a ticket stub from a famous 1996 game or a certificate of another famous game. After returning the survey, participants were given the opportunity to trade (i.e. exchange) the good they had received for the other option. 44% of professional traders and 47% of non-professional experienced traders traded their gift. However, only 7% of novice sports card traders traded their gift. This was a clear case of endowment effect. It seems the less expertise we have in an area, the more likely we will suffer from endowment bias. However, even experienced traders suffer from endowment bias in other areas of their life where they might have less expertise and knowledge.[10]

This finding is also supported by recent neuroscientific research conducted at the University of Chicago. Researchers found that while selling, experienced traders showed reduced activity in an area of the brain often associated with pain and negative emotions, suggesting that the traders experienced little or no loss aversion. A separate experiment showed a similar reduction in brain activity after people previously inexperienced in trading were given incentives to trade items on eBay for just two months.[11]

An additional factor that may play a role in dampening the endowment effect is whether the buyer or the seller feels as though they are getting a ‘good deal’. Previous research has suggested that when buying or selling an item, people not only consider the benefits of the goods but also whether they feel they are being taken advantage of or made a fool of, i.e. whether the price of the good was higher or lower than they expected (where their expectations are formed from salient reference points; such as the typical retail price). With this in mind, a study conducted in 2012 tested whether in some situations, the endowment effect might be a reluctance to trade an item on unfavorable terms. More specifically, the researchers predicted that the endowment effect would be exacerbated if and when the expected price deviates from what the item is actually worth.

Researchers tested this idea in six lab experiments by artificially manipulating the reference price of an item, to either widen or narrow the gap between this reference price and the expected price of both the buyer and the seller. For example, in one study participants were given a mechanical pencil with a sticker price that varied between $0.79 - $2.29. If the seller believed the pencil was worth $2, their willingness to sell would be higher as the reference price got closer to this. Consequently, as the difference between the reference price and the expected price shrank, so too did the observed endowment effect of the seller.

This seems to support the idea that both parties are trying to ensure a ‘good deal’ for themselves; sellers may value their mechanical pencil at $2 but if they know the going rate for that item is only $1.50 they will accept a lower price if they believe it reflects the market rate. Similarly, buyers won’t be keen to purchase an item for over the market price. It is worth remembering however, that given the lab-based context of the study, participants would likely have felt very observed and possibly in competition with their peers to ‘do a good deal’ which may have affected observed behaviour.

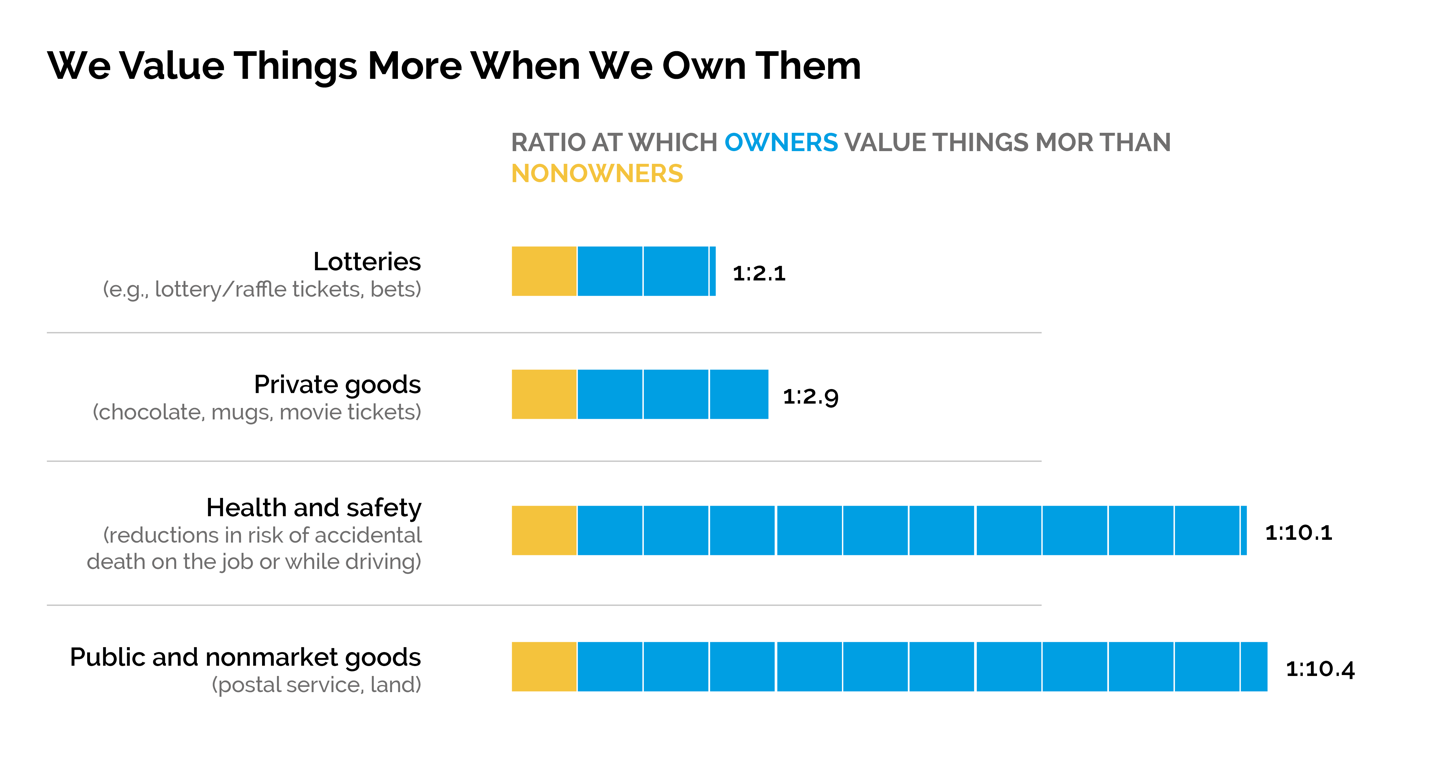

The type of good might also affect the intensity of the endowment effect. Typically, sellers’ willingness or demanded price to give up an item is usually about two or three times as much as buyers are willing to pay to acquire it. This gap is even higher for more unique and abstract goods. Research by John Horowitz and Kenneth McConnell found that the less ordinary an item, the higher the ratio.[12] (see chart)

Finally, feelings of endowment may also vary across cultures. In 2010, researchers investigated whether the endowment effect varies across Eastern (in this case, Japan) and Western cultures. They designed the study based on the mug experiment: half of the students received a coffee mug and were asked to trade with the other half. Even though the endowment effect was present for participants from both cultures, the effect was significantly larger in Western than Eastern cultures.[13]

The researchers suggest that cultural differences in self-enhancement may explain the results. People in Western cultures are more likely to associate themselves with objects to make themselves feel good and increase their self-esteem. Eastern cultures tend to have a more interconnected perspective of themselves and focus less on individual gains and self-expression, instead self-criticism seems to be a more dominant theme. Or perhaps the reason for the difference is simply because mugs are not as common in Japan as they are in western countries like the UK and America and as such they are valued differently.

The future

We now have a far better and broader understanding than we did have about possible mechanisms and explanations behind the endowment effect - beyond loss aversion, feelings of ownership or framing effects may also have a potential explanatory effect. Although further research is still needed to reach a consensus on which mechanism might operate where, and to explore the effect in real-world contexts with diverse populations, we’re in a stronger position than before.

We’re also developing an understanding of how various contexts affect the strength of the endowment effect, particularly in an era of rapid change in types of ownership and purchasing channels. Many of our decisions and choices are increasingly made online and when people - particularly younger generations - are purchasing fewer tangible items such as CDs and cars and moving more towards a subscription, rental or sharing economy. Understanding whether feelings of ownership can still be generated in these contexts will be important.

Conclusion

Better understanding the endowment effect is valuable. We know that endowment effects can create substantial friction or log jams in negotiations, such as mergers and acquisitions, in auctions, or simply haggling for a sought-after souvenir. It may even lead to a stalemate, with both parties walking out from the table, unable to reach an agreement. It’s equally important to better understand how it works and the extent to which it influences our decisions in the growing digital world. We’ve moved a long way from mugs and bottles of wine; let’s celebrate this wider understanding and eagerly await the new insights still waiting to be discovered.

New Frontiers in Behavioural Science Series:

Article 1 - The Past, The Present and The Future

Article 2 - Default Settings - The most powerful tool in the behavioural scientist's toolbox

Article 3 - Social norms and conformity part 1

Article 4 - Social norms and conformity part 2

Article 5 - System 1 and System 2 thinking

Article 6 - When is choice a paradox?

About the authors:

Crawford Hollingworth is co-Founder of The Behavioural Architects, which he launched in 2011 with co-Founders Sian Davies and Sarah Davies. He was also founder of HeadlightVision in London and New York, a behavioural trends research consultancy. HeadlightVision was acquired by WPP in 2003. He has written and spoken widely on the subject of behavioural economics for various institutions and publications, including the Market Research Society, Marketing Society, Market Leader, Aura, AQR, London Business School and Impact magazine. Crawford is a Fellow of The Marketing Society and Royal Society of Arts.

Liz Barker is Global Head of BE Intelligence & Networks at The Behavioural Architects, advancing the application of behavioural science by bridging the worlds of academia and business. Her background is in Economics, particularly the application of behavioural economics across a wide range of fields, from global business and finance to international development. Liz has a BA and MSc in Economics from Cambridge and Oxford.

[1] Kahneman, Daniel, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler. 1991. "Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5 (1): 193-206.

[2] Kahneman, Daniel, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler. 1991. "Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5 (1): 193-206.

[3] Morewedge, C.K. et al. (2009) Bad riddance or good rubbish? Ownership and not loss aversion causes the endowment effect. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45, 947–951

[4] Brasel, S.A., and Gips, J., (2014) “Tablets, touchscreens, and touchpads: How varying touch interfaces trigger psychological ownership and endowment” J. Consumer Psychology. 24, 226-233

[5] Kim, K. and Johnson, M.K. (2014) Extended self: spontaneous activation of medial prefrontal cortex by objects that are ‘mine’. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9, 1006–1012

[6] Morewedge, C.K. and Giblin, C.E. ‘Explanations of the endowment effect: an integrative review’ Trends

In Cognitive Sciences, June 2015, Vol. 19, No. 6

[7] https://hbr.org/2016/05/why-buyers-and-sellers-inherently-disagree-on-what-things-are-worth

[8] Strahilevitz, M.A. and Loewenstein, G. (1998) The effect of ownership history on the valuation of objects. J. Consum. Res. 25, 276–289

[9] Reb, J. and Connolly, T. (2007) Possession, feelings of ownership, and the endowment effect. Judgement & Decision Making. 2, 107–114

[10] List, J.A. (2003) Does market experience eliminate market anomalies? Q. J. Econ. 118, 41–71

[11] Tong et al “Trading experience modulates anterior insula to reduce the endowment effect” PNAS 2016 http://www.pnas.org/content/113/33/9238.full; and https://news.uchicago.edu/article/2016/08/01/trading-changes-how-brain-processes-selling-decisions

[12] Horowitz, J., and McConnell, K. ‘A Review of WTA/WTP Studies’, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Volume 44, Issue 3, November 2002, Pages 426-447

[13] Maddux, W. W., Yang, H., Falk, C., Adam, H., Adair, W., Endo, Y., . . . Heine, S. J. (2010). For whom is parting with possessions more painful? cultural differences in the endowment effect. Psychological Science, 21(12), 1910-1917.