What situations or individual characteristics might make framing effects - like the ones we outlined in our previous article - stronger or weaker? Researchers are now beginning to identify some of these factors, which we will explore below.

How environmental contexts affect gain versus loss framing: Much of the research into goal framing - when the goal of an action or behaviour is framed - has focused on health and healthcare. Given that problems such as obesity, diabetes and cancer are some of the most pressing of our time, this has inevitably led researchers, practitioners and clinicians to ask which type of frame for behavioural change campaigns is more effective.

In the healthcare context, experts thought loss-framed appeals were more persuasive than gain-framed ones. This draws on the theory of loss aversion, which holds that in human psychology, losses loom larger than gains. However, a 2009 review of 53 studies on disease detection behaviour found that in some cases the impact of loss framing was small and in many cases there was no difference between loss- and gain-framed messages. They concluded that there was no real difference in the efficacy of each type of frame.

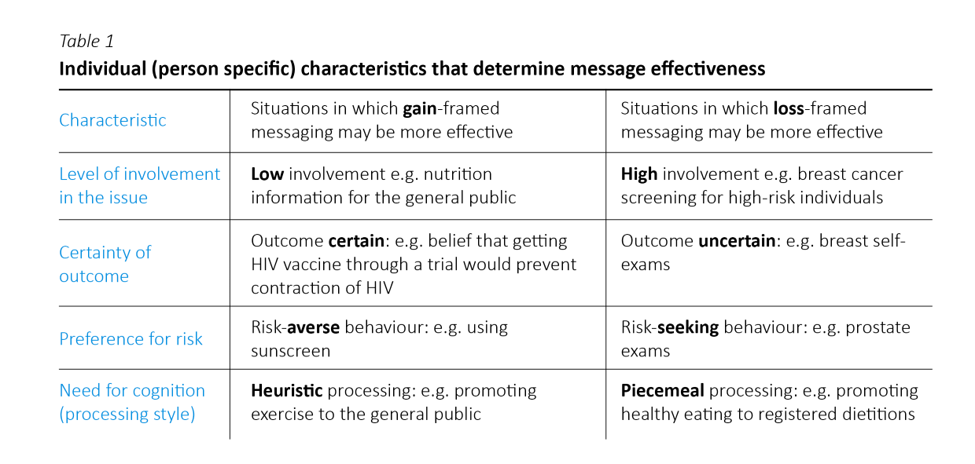

A more recent review attempts to define certain rules or conditions for when gain framing or loss framing might be more appropriate in different health contexts. Researchers identified four key questions that could help to determine which type of message might be more effective depending on the context or individual. This allowed them to personalise the message to the audience in question:

- Are you highly involved in this issue?

- Is the outcome uncertain?

- Are you risk averse?

- Are you detail-oriented?

If the answer is ‘yes’ to many of the questions for the individual(s) in question, a loss-framed message may work better.[1] If the answer is no to most of the questions, a gain-framed message may be more appropriate.

Source: Wansink and Pope, 2015

How time pressure increases the framing effect: Some of the original studies looking at framing asked people to respond to hypothetical scenarios. These were non-pressured situations, where participants could take their time to give their answer. However, in real-life, we are often called upon to make an immediate decision after being presented with information; perhaps in a business meeting, in an interview, whilst driving, in an exam or even just during a heated debate with friends over dinner. Are we more susceptible to framing effects in these sorts of time-pressured contexts? Research published in 2017, looking at both hypothetical and incentivised contexts for gambling decisions, suggests yes. People asked to ‘respond quickly’ and given a time limit of just 1 second were more prone to framing effects. Faced with a gain frame, people under time pressure were more risk averse. Given a loss frame, people were more risk seeking – hoping to avoid the loss. This supports the belief, and earlier neuroscientific evidence, that framing effects typically originate from our ‘System 1’; our fast, intuitive decision-making system.[2]

How individual characteristics influence framing: Are some people more susceptible to framing effects than others? Older individuals, for example, have a greater tendency to focus on, seek out and remember positive emotional experiences - contrary to stereotype! They tend to find positive information more salient, whilst either not noticing or forgetting negative messages.[3] In turn, this may mean they notice and prefer positive frames – gain frames - as opposed to negative, loss focused ones.

There is also some evidence to suggest that older people could be more affected by framing, although research is limited and mixed. It may actually be less related to absolute age and more connected to the extent of cognitive decline someone has experienced. As we age, our fluid intelligence - functions such as working memory, processing speed, and reasoning - declines. This is offset, to a certain degree, by increases in what’s known as our crystallised intelligence - functions such as knowledge, experience and expertise. However, after age 60 or so, even this plateaus and begins to decline after around age 70; leading to an eventual downward trend in decision-making ability in later years.[4] We could speculate that in these late years we might be more likely to be affected by framing.

However, this peak and decline in crystallised intelligence may now appear later in life as education levels, health and nutrition improve. A 2015 study at MIT and Harvard by Joshua Hartshorne and Laura Germine found that vocabulary tests revealed a peak in crystallised intelligence in people’s late 60s and even early 70s. The same study also found that peaks in measures of fluid intelligence varied – some peaked early in life whilst others did not peak until age 40.[5] Therefore, susceptibility to framing effects in old age may be highly varied across individuals, where environmental factors such as nutrition and genetics seem to affect the speed of cognitive decline. Indeed, a 2018 study demonstrated that cognitive abilities such as strategic control and delayed memory better predicted susceptibility to framing effects than age.[6]

Linked to this finding is research which suggests that people who are less numerate can be more influenced by framing effects, particularly if people see percentages rather than natural frequencies - a type of framing discussed in our previous article. It’s thought that less numerate people are less attentive or focused on numerical information than more numerate individuals so their judgements tend to - have to, even - rely more heavily on any positive and negative words and scenarios that create the framing effect, an outcome identified in a 2017 study.[7]

The future

It’s clear that framing is a powerful tool in decision-making. The human mind cannot help but be affected by how information is presented. However, behavioural science is only just beginning to discover some of the nuances that can strengthen or weaken the framing effect - both contextual factors and individual characteristics. And whilst we are learning about what sort of frames are effective in some contexts such as health and healthcare, there are many other areas and sectors to better understand.

Individual characteristics that affect framing is a particularly exciting and dynamic area in an era of personalised messaging, driven by algorithms and personal data. We are starting to understand what characteristics drive framing effects and preferences for how information is presented, but new areas are still being explored and better understood.

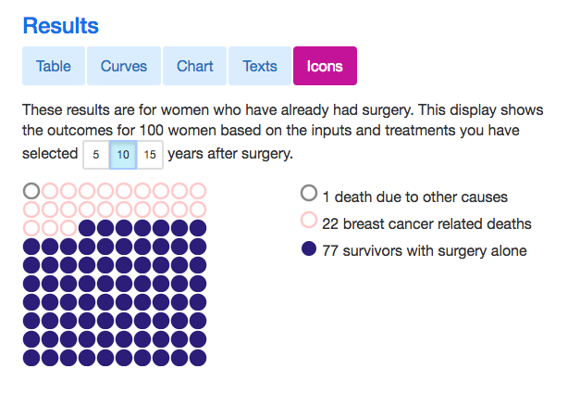

One example is an algorithm-based tool called PREDICT, which helps medical professionals advise women who have just been diagnosed with breast cancer about their treatment options. This tool, implemented through the NHS, is helping to build an understanding of what type of information - visual or text-based - on treatment options, risks and survival rates is preferred and best understood by patients.

One example is an algorithm-based tool called PREDICT, which helps medical professionals advise women who have just been diagnosed with breast cancer about their treatment options. This tool, implemented through the NHS, is helping to build an understanding of what type of information - visual or text-based - on treatment options, risks and survival rates is preferred and best understood by patients.

Somewhat unexpectedly, the team has found that there is no ‘best’ way of explaining the different options to each patient. Individual preferences vary greatly based on a person’s numerical, verbal, or graphical skills and understanding. One size definitely does not fit all. As a result, they developed five different displays for communicating the data, improving each one over time based on patient feedback.

These iterations have revealed some fascinating preferences among patients. For example, the ‘Icons’ display showing natural frequencies (see image) initially displayed stick figures in different colours to represent patient outcomes; with eventual prognosis of death represented by stick figures coloured in black. Perhaps unsurprisingly, patients were put-off by this graphical presentation. Once these were changed to blue coloured dots, this type of presentation became much more popular with patients, presumably because death felt less personal and salient.[8] Subtle changes in design or tiny changes in linguistics could make all the difference - and provide ripe opportunity for testing.

Conclusion

The framing effect was first identified close to 40 years ago. Over the past decades, researchers have identified a number of different types of framing effects, demonstrating the extent of its influence on our judgement, understanding and decision-making, as explored in our previous article; part one of framing. In part two, we’ve explored how framing effects can vary depending on the surrounding context and situation, on time pressure and on individual characteristics – particularly age and cognitive abilities.

Researchers are still exploring new avenues and fine-tuning our understanding of framing effects; looking at a variety of contextual influences on the effectiveness of framing. For behavioural science practitioners, this continued research is highly valuable; it will help us more effectively tailor information, better guide decisions and optimise and improve people’s understanding of information.

Why it matters:

Depending on the context, one frame may be more effective than another. For example, gain framing a message may be more effective than loss framing or vice versa. Having a deeper, more nuanced understanding of these contextual factors that may influence the effectiveness of a behavioural frame will help researchers and practitioners better communicate information to the public and ultimately get closer to achieving the desired behavioural change.

Key takeaways:

- Contrary to what has previously been thought, loss-framed appeals in the healthcare contexts aren’t necessarily always more persuasive than gain-framed ones. In fact, in some cases, a gain-framed message may be more effective. For example, a gain-framed message is more effective if the individual were to answer ‘no’ to the following questions: Are you highly involved in this issue?; Is the outcome uncertain?; Are you risk averse?; Are you detail-oriented?

- Time pressure also appears to increase our susceptibility to framing effects, as does age; the older we get, the more receptive we are to positively-framed information.

- Individual characteristics that affect framing is a particularly exciting and dynamic area in an era of bespoke messaging. Tools are already being developed (such as PREDICT) to present information in a way that is optimal for the individual receiving it.

[1] Wansink, B., & Pope, L. (2015). When do gain-framed health messages work better than fear appeals? Nutrition Reviews, 73(1), 4.

[2] Lisa Guo, Jennifer S. Trueblood and Adele Diederich, “Thinking Fast Increases Framing Effects in Risky Decision Making” Psychological Science 2017, Vol. 28(4) 530–543

[3] https://www.marketingsociety.com/the-library/why-we-think-and-behave-differently-we-age-part-2#FrwdLajqAAL4vtaA.97

[4] Salthouse TA (2004) What and when of cognitive aging. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 13(4): 140–144;

[5] Hartshorne, Joshua K. & Germine, Laura T. (2015). ‘When does cognitive

functioning peak? The asynchronous rise and fall of different cognitive abilities across the lifespan’,

Psychological Science, 26(4), 433–443 and MIT News: http://news.mit.edu/2015/brain-peaks-at-different-

ages-0306

[6] Perez, A. M., Spence, J. S., Kiel, L. D., Venza, E. E., & Chapman, S. B. (2018). Influential Cognitive Processes on Framing Biases in Aging. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 661. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00661

[7] Gamliel, E., Kreiner H. (2017) “Outcome proportions, numeracy, and attribute‐framing bias”, Australian Journal of Psychology, Volume 69, Issue 4, Pages 283-292

[8] NHS Predict Tool - https://www.predict.nhs.uk/tool; NeurIPS talk by D. Spiegelhalter - https://www.facebook.com/nipsfoundation/videos/482957018893956/

Candido dos Reis et al, (2017) “An updated PREDICT breast cancer prognostication and treatment benefit prediction model with independent validation” Breast Cancer Research, 19:58

New Frontiers in Behavioural Science Series:

Article 1 - The Past, The Present and The Future

Article 2 - Default Settings - The most powerful tool in the behavioural scientist's toolbox

Article 3 - Social norms and conformity part 1

Article 4 - Social norms and conformity part 2

Article 5 - System 1 and System 2 thinking

Article 6 - When is choice a paradox?

Article 7 - Beyond mugs and wine

About the authors:

Crawford Hollingworth is co-Founder of The Behavioural Architects, which he launched in 2011 with co-Founders Sian Davies and Sarah Davies. He was also founder of HeadlightVision in London and New York, a behavioural trends research consultancy. HeadlightVision was acquired by WPP in 2003. He has written and spoken widely on the subject of behavioural economics for various institutions and publications, including the Market Research Society, Marketing Society, Market Leader, Aura, AQR, London Business School and Impact magazine. Crawford is a Fellow of The Marketing Society and Royal Society of Arts.

Liz Barker is Global Head of BE Intelligence & Networks at The Behavioural Architects, advancing the application of behavioural science by bridging the worlds of academia and business. Her background is in Economics, particularly the application of behavioural economics across a wide range of fields, from global business and finance to international development. Liz has a BA and MSc in Economics from Cambridge and Oxford.