Over the last month we have seen a wide spectrum of behavioural responses to Covid-19 in society, from the few who seem to just ignore all advice to those too scared to leave home. Why is this the case? Why do some people seem to be taking the risk posed by the coronavirus pandemic very seriously, and in some cases overestimating the probabilities of risk to themselves, while others seem reluctant to change their behaviour at all and appear to be underestimating the risk to society? While these varying degrees of response may at first appear perplexing, behavioural science enables us to make sense of the reactions we are seeing.

First let’s look at the Availability Heuristic and how this can influence how we assess risk

The availability heuristic refers to a decision-making shortcut that helps us assess the probability of risk. Rather than taking into account the true probabilities of risks, we often judge the likelihood of an event, or the frequency of its occurrence by what is most vivid and salient to us and the ease with which examples and instances come to mind.

When we’ve heard or read about something a lot - for instance the increasing number of coronavirus cases and death rates - it becomes so easy to imagine ourselves or our families contracting the virus that we may overestimate the actual personal risk to ourselves and panic as a result. It’s also a very brutal disease at its worst, and reports and photos from medics treating patients in hospitals make it even more vivid in our minds. Like death due to a terrorist attack, coronavirus is what is known as a ‘dread risk’ – something which invokes considerable fear. Dying, not being able to breathe, alone, away from our loved ones is an alarming and upsetting vision.

Consequently, it’s top of mind. Recent media analytics indicate that in just one day (11th March 2020) there were 20 million mentions of coronavirus-related terms over social media and the news. To give some indication of how large this number is, on the same day there were only around 4 million mentions of Trump and under 2 million mentions of the just cancelled NBA games. Similarly, we are seeing daily updates on the number of reported deaths from coronavirus – all over the world. These figures are still relatively small compared to deaths caused by other diseases but the daily reporting means that ‘death by coronavirus’ is a highly salient - ‘available’ - topic in our minds.

Availability bias in this way can cause subsequent panic and fear, and panicking may have actually lead to an increase in some of the negative behaviours we are hoping to see stop, e.g. going to A&E when you suspect symptoms or buying the shop’s full supply of cough medicine and paracetamol. Better understanding our availability bias can help us reduce this fear and panic within society. For example, there are a number of online self-help guides suggesting that we limit our ‘news time’ to a maximum of an hour a day.

We need behavioural feedback, but in the current context it can be hard to see the direct impact of our actions.

If people receive timely and personalised feedback on a task, it can motivate them, increase their engagement and, ultimately, help them achieve their goal. You drive faster, you see your mpg fall; you go for a walk, you see your step count rise; you phone your insurance company and are told where you are in the queue and how long you’ll need to wait. All these types of feedback help us see the impact of our behaviours. The coronavirus is the exact opposite – as a silent spreader there is no immediate feedback on transmission and if there is any at all, it comes with such long time lags that it’s difficult to stop people deviating from the standard social distancing, hygiene and isolation guidance. For one, the virus has a much longer incubation period than the influenza – 2-11 days versus just over 1 day, and transmission of the virus is invisible. Secondly, it’s usually 7-10 days before symptoms worsen and 17 days on average before someone dies from it. Lack of real-time feedback means that it’s hard for people to feel they are making a difference by staying inside.

In western society it is hard to avoid the Free rider problem – we all like to push the bar just a little

It’s hard for people to not try to cheat the lockdown a little…known as the free rider problem. In the case of Covid-19, staying at home is less about risk to yourself (unless you are over 60 or have underlying health issues) but about taking precautions to slow the spread of the disease for the collective good of society so hospitals are not overwhelmed and the virus can be suppressed for the time being so we can better prepare and another strategy can be adopted. Yet, if someone perceives the risk to themselves as being tiny, perhaps because they see no evidence of the virus around them, it’s very easy for them to reason ‘just one visit to my friend won’t make any difference’ or ‘one drive out to the beach won’t matter’.

But if everyone adopts this mentality, the strategy is undermined. For lockdown to be successful, it’s about being selfless, not selfish.

Authorities have only been communicating with the numerate few!

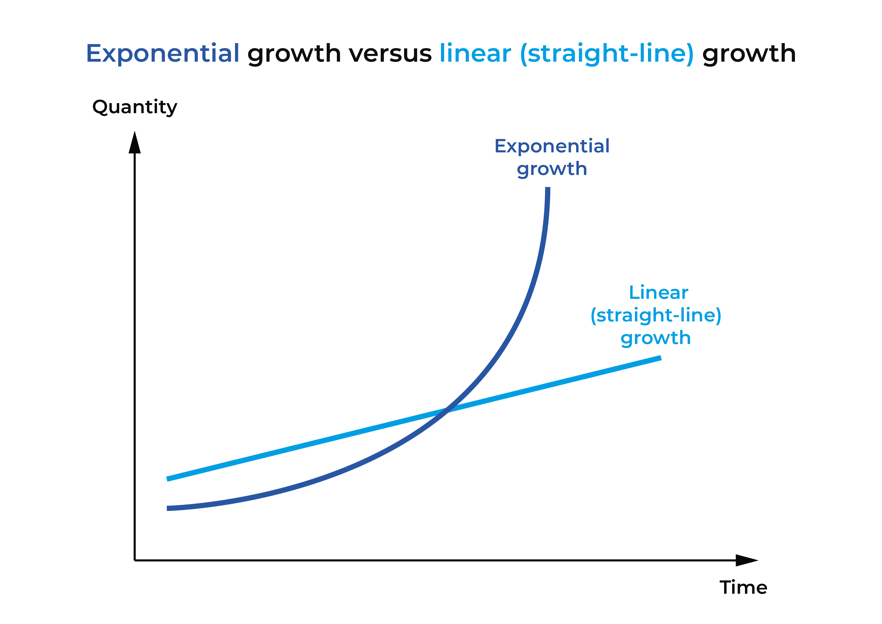

Many of us are not that comfortable dealing with numbers, models, graphs and predictions. One particular problem stemming from this for understanding disease is grasping the concept of exponential growth. Exponential growth doubles every increment which means that it grows very slowly at first, but rapidly accelerates. Max Roser, who runs ourworldindata.org at the University of Oxford, one of the data collations on Covid-19, highlights this issue:

“Psychologists find that humans tend to think in linear growth processes (1, 2, 3, 4) even when it doesn’t appropriately describe the reality in front of our eyes. This is called exponential growth bias.”[1]

The Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman even admitted he did not fully realise the severity of the threat initially:

“People, certainly including myself, don’t seem to be able to think straight about exponential growth. What we see today are infections that occurred 2 or 3 weeks ago and the deaths today are people who got infected 4 or 5 weeks ago. All of this is I think beyond intuitive human comprehension.”[2]

While it does mean we have ‘yet another bias’ to add to the ever-growing list, it is useful to conceptualise this problem specifically. It also links to the free rider problem about why people struggle to understand why they need to stay at home when the risk still feels so small. They may struggle to visualise something growing exponentially.

We are all drawn to the desire for normalcy or normality and find it hard to imagine radical change – we hold on to the now.

As humans we tend to believe that things will function in the future the way they have normally functioned in the past and therefore to underestimate both the likelihood of a disaster or pandemic and its possible aftereffects. Even as recently as February we found it hard to imagine we might need to change our lives as much as they have done – that international travel has more or less halted, that hospitals are overwhelmed, schools shut, healthcare workers are held up as heroes and anyone that can now works from home.

Before 2008, we found it hard to imagine a global financial crisis as huge and as damaging as what transpired. Before 2001, it never occurred to us that terrorists might fly planes into the twin towers in New York. We are continually surprised by the more frequent and increasingly damaging extreme weather events which are occurring as a result of climate change. We just can’t imagine floods, or droughts or wildfires any worse than those that have happened. Until we take decisive action, our weather system is not ever going to ‘go back to normal’.

With the advent of coronavirus and the recognition that global pandemics are increasingly likely in our hyperconnected, overpopulated and increasingly urban world, we are unlikely to return to the pre-2020 ‘normal’.

This human desire for normality works hand in hand with our focus on the present known as the present bias

Present bias, or hyperbolic discounting, refers to the tendency of people to give stronger weight to payoffs that are closer to the present time when considering trade-offs between two different time periods. In other words, we tend to overly focus on the needs and wants of today rather than think about what tomorrow might offer. This can often lead us to procrastinate on tasks or activities that are not fun or rewarding in the moment but would be beneficial for our future selves, like saving or going for a run.

In terms of the current crisis, this could have quite serious consequences. Self-isolation mostly requires us to think past our present wants and desires. Indeed, we must sacrifice this time now to help preserve our society’s future. With this in mind, it becomes easier to understand the behaviour of those still leaving their homes; the lure of our present wants to override the future benefits that would come from remaining at home. As such, it is understandably very difficult for the vast majority to remain self-isolated at home; made harder still by not having much (if any) clarity over how far away these future rewards are.

Usually an essential and uplifting bias is that we have a tendency to view the future through rose coloured spectacles known as the Optimism bias:

Optimism bias refers to our tendency to overestimate our likelihood of experiencing good events in our lives and underestimating the likelihood of suffering from negative events. With respect to coronavirus, the impact on our behaviour is pretty obvious, particularly among younger members of society. I’m sure we all have that friend who has said - or indeed have muttered to ourselves over the past few months - “I’ll be fine! It won’t happen to me” or more broadly “It’ll be fine – governments will get it all under control before it becomes a real problem.” Again, it is this attitude that may have prevented people from taking any action.

Behavioural science offers a number of tools to help dial down optimism bias. Firstly, we can reframe the coronavirus message. Rather than emphasising those who are more likely to catch and badly suffer from the virus, we can reframe the message around the spreading of the virus. Everyone has the potential to be a carrier, and in fact younger people are more of a problem when it comes to spreading the virus as it’s thought that they often show very mild (if any) symptoms. Emphasising this might help to change perceptions among younger people, dialling down their optimism bias and helping them take responsibility as a potential spreader. We’re starting to see this being talked about more, specifically with reference to ‘silent spreaders’ or ‘unseen carriers’ or even ‘super-spreaders’.

Secondly, we can provide new anchors or reference points. Anchoring people to the need to protect their grandparents or parents, other vulnerable members of their family, or more vulnerable friends – those who have hypertension, diabetes or cardiovascular disease - may help encourage more compliant behaviour because even if they are not personally concerned about contracting the virus, they likely are concerned for their loved ones. We all probably know someone who falls into either the elderly or vulnerable categories so it is easy to help people relate to the need to protect. Similarly, behavioural science teaches us that we are much more responsive to one, identifiable victim rather than a mass of numbers – this is already being seen in the media and social media.

We all love to follow the crowd but it takes time to find or see the new norms – injunctive or descriptive:

The concept of social norms in behavioural science refers to our tendency to conform to the behaviours of those around us. There are two main types of social norms: descriptive and injunctive. Descriptive norms refers to our tendency to want to follow the behaviours of the majority, and injunctive norms describe behaviours we perceive of being approved of by others – what we know we should be doing.

During this highly disruptive time, we will look to those around us to help guide our decisions around the actions we will - or will not - take. If we believe or can see that a behaviour like social distancing or self-isolation is something that everyone else around us is engaging with, we are much more likely to conform with this behaviour ourselves.

This is why pictures of crowds of people going to the beach or to public parks on the weekend can be so damaging in terms of behaviour change; the descriptive norm here is that people aren’t complying and if we believe others aren’t complying… and we were on the fence about complying, we probably won’t either!

As such, this is an incredibly powerful concept to be aware of during this crisis. Firstly, it can help explain why some communities appear to be complying to government advice more than others, and secondly it provides the government and others with a powerful tool to influence the desired behaviour. By pointing out what the vast majority of people are doing, practitioners can help curate a strong sense of joint and coordinated action. First Minister for Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon on her twitter account has been making good use of descriptive norms to try and encourage more compliant behaviour (see below). She has also continued to praise those doing it right.

As time has gone on, we have more visibility over compliance – the empty roads outside your house, the empty railway stations or tubes, etc so we now have opportunities to use more descriptive norm messaging.

Another interesting development is the evolution of the injunctive norms around social distancing. Photos of crowded tubes and trains were posted online with captions aimed to publicly shame the behaviour, calling it “selfish” and “irresponsible”. Similarly, we’ve seen these images, as well as pictures of empty shelves in shops and of people stockpiling goods, presented on the news with reporters also using the words “selfish” and shaming any panic buyers. On social media too, individuals are calling out those around them – even people they know. As such, the injunctive norm around this kind of behaviour is changing; it has become less socially acceptable to be out and about unless where necessary and hoarding essential items is actively frowned up.

Tapping into our sense of social and group identities is also a highly effective behaviour change tool. For example, Prime Minister, Boris Johnson’s speech about imposing greater lockdown measures on March 23rd spoke to our nation’s identity as British, tapping into national pride, and referencing World War Two and our success in standing strong together. As social beings we derive meaning and direction from the groups we closely identify with and gain value from identity-affirming behaviour. This means that if we are able to tap into what it means to be British, and align the desired behaviour with these British values (i.e. us Brits have come together and risen up to an enemy before, we will come together and succeed again) then we are much more likely to comply.

We all love an Authority short cut but adjusting to who are the new authorities and who to trust takes time:

The authority heuristic refers to our tendency to alter our opinions or behaviours to those of someone we consider to be an authority on a subject. People follow the lead of people they believe to be credible and knowledgeable experts when they are unsure. As such, we tend to use authority as a mental shortcut. The most commonly cited example of this might be trusting in a toothpaste brand that is recommended by a smiling dentist in a clean, white lab coat!

During times of national crisis and uncertainty, we are now - more than ever - looking to authority figures to guide our understanding and decision making. When it comes to looking up symptoms, for example, it is important to look to reliable sources to ensure we are absorbing the correct information and advice; i.e. seeing a piece of advice from organisations such as the WHO or with an NHS stamp of approval, reassures us that the information is trustworthy. An even simpler authority short cut is seeing people we look up to, role models such as celebrity actors or sporting icons doing the right things and telling us so – and is obviously less political!

Similarly, thre years ago Finland formally adopted the use of influencers in their emergency plan given that many social influencers now reach the same number of people as newspapers or radio. So when Covid-19 hit, the government asked its team of influencers – just regular, but popular Finnish citizens – to disseminate key information. This has helped to ensure the right information gets to people – usually younger generations – who don’t use traditional media.[3]

However, we must be careful how we utilise authority as sometimes it can backfire. A good example of this is when an early coronavirus patient posted a video on youtube discussing ways to tackle and prevent the spread of the disease. The advice, however, was flawed and for the most part full of myths. Youtube tried to let viewers know this by placing a link to the WHO on the webpage. However, most viewers saw the WHO logo and took this to be a verification and approval of the advice! They assumed that an authority such as the WHO had given the video their stamp of approval.

Trust in authority is also key. If we start to mistrust the authority, we are less likely to follow their advice. We saw this initial backlash in the UK when the UK government originally seemed to be giving us advice that deviated from the rest of Europe. It planted seeds of doubt, dividing the nation into those who trusted the government’s approach, and those that didn't. The lack of visible and co-ordinated action to boost testing capacity, supplies of PPE and other medical equipment is also undermining the government’s trustworthiness. Authority can be a powerful tool for behaviour change when the authority figure is credible and reliable.

In summary

Covid-19 is not only a huge disruption across the world, but it is also disrupting our brains. As you can see above, we have so many heuristics and biases playing on our brain at this time it is simply overwhelming as we adjust. As Kahneman says, much of this is what has been happening this year is beyond human comprehension.

Therefore, communications need to be acutely sensitive to this context, designed with equal measures of care, thought and logic. More than ever, we need to be adjusting, updating and adapting our communications to this new context. To define the audience and strategic communication objectives tightly. To be very clear what core behavioural or emotional outcomes the communication is targeting.

This thinking and contextual analysis has inspired the development of our Covid-19 Behavioural science toolkit ‘Communicating in Lockdown Times’.

This piece was by Crawford Hollingworth. To read all content from The Behavioural Architects please click on the author name at the top of this page.

[1] Source: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

[2] Source: Interview with Daniel Kahneman, The New Yorker, 3rd April 2020

[3] https://www.politico.eu/article/finland-taps-influencers-as-critical-actors-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/