This is the second article in our three-part series. In part one we explored common misunderstandings around nudging. The widespread use has created a huge range of impacts and expectations. As a result, there is a need for a more strategic approach to nudging, a framework that anyone can use to set clear expectations of the potential impact of any nudge.

In this article, we illustrate how the impact of a nudge might be marginal as well as major and how variation is to be expected depending on the context.

The latest behavioural science research has consistently found that the impact of any nudge actually falls along a spectrum; meaning not all behavioural interventions will have the same impact - some are more powerful, others more marginal, and in some contexts, some can have no or even a negative impact. A single one-point-in-time nudge may also be limited in its impact compared to a more holistic, multi-pronged strategy for behaviour change, changing multiple aspects of the context or nudging at multiple points of time during the consumer journey.

This is partly because a nudge is a wraparound term for a multitude of tools. The word ‘nudge’ is actually quite loosely defined; in their 2008 bestseller ‘Nudge’, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein defined the term as “choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.”. Whilst some tools result in micro-impacts, others make more radical changes.

These tools include changing the default, emphasising peer behaviours and social norms, leveraging concepts such as anchoring and framing, making information simpler and easier to read, or asking people to make a simple plan of action (known as implementation intentions). These have all been put into action in different contexts with a wide range of people with the goal to change behaviour. Even a concept that can have radical impacts on choice and behaviour in one space may be marginal in another; it’s out of our control.

In addition, the impact of any intervention is often given as an average where, in reality, it may have changed the behaviour of some consumers a lot, some a little, and some perhaps not at all. It may even have backfired. For example, in a recent field trial, messaging which emphasised saving for retirement to help “secure your family’s future” increased contributions by 89% for those 28 and over, yet for younger individuals it backfired and led them to reduce contributions by 53%, likely due to them being in a different life stage. The messaging felt irrelevant to them.

Some recent reviews have pointlessly sought to calculate the average impact of a nudge by looking at hundreds of behavioural change trials altogether. But experts say that the average effect tells us nothing, highlighting that the real message is the wide variations in impacts, from very small to sizeable. They question why anyone would try to seek an average in such a mixed contextual arena. As statistician Beth Tipton of Northwestern University says, “The heterogeneity IS the story” and we should expect it.

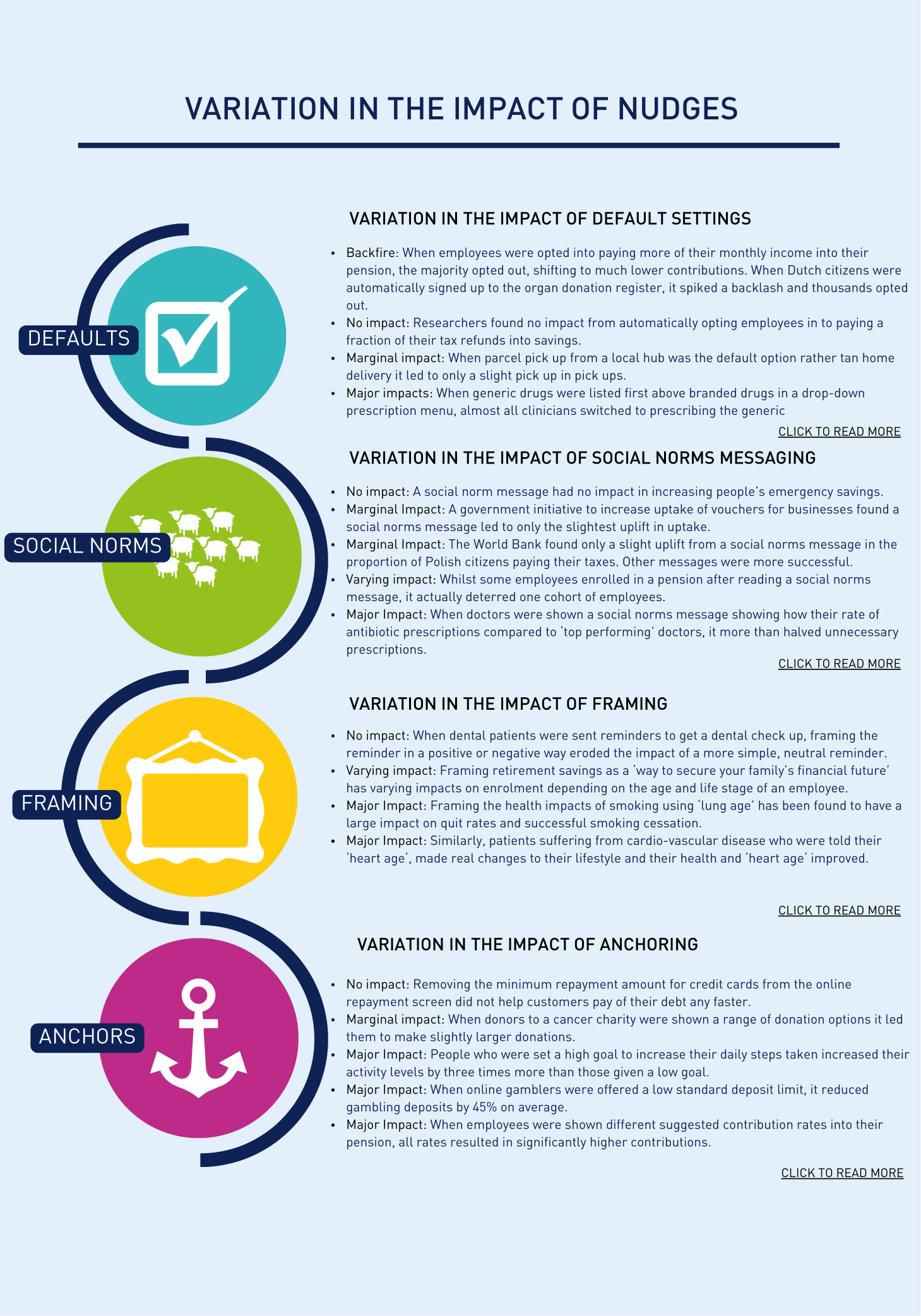

Illustrating the wide range of impact of a nudge

To help illustrate this idea of variation we look at the variation in impact for four well-known behavioural science concepts in the tables below. Some behavioural science concepts are better researched than others, so we have selected those with a broader and stronger research base - namely defaults, social norms, anchoring and framing .

• Defaults: We tend to stick with what has already been selected for us – the ‘default’ – rather than think harder to make our own decision

• Social norms: We like to do what others are doing and look to other people to guide us – valuing their opinions and emulating their behaviours.

• Framing: The way information is presented – ordered or framed – has a significant impact on decision making. For example, it might focus on what people might gain or lose.

• Anchoring: We look for reference points (anchors) that we can rely on and adjust our judgements and decisions from

We look at findings from a range of studies which found varying impacts on behaviour, from marginal to major impacts, or even zero to negative impacts in different contexts. The lists are not exhaustive, but designed to give a picture of the breadth of impact. For example, in one case, defaults had no impact in boosting savings when employees were automatically opted into paying some of their tax refund into savings bonds – people simply opted out as they had other items they needed to fund. But changing the default order of a drop down menu had a major impact in clinicians prescribing generic drugs rather than the more expensive branded option. And anchoring shows a wide range of impact too – removing the minimum payment on a credit card bill – a number consumers often anchor to when making repayments – did not lead consumers to repay their debt any faster. But anchors did have major impacts in reducing the size of gambling deposits and increasing the size of pension contributions.

(click on the image above to access the pop-outs)

This article – part two in our series – explored why we need to acknowledge that not all nudges are equal – how impacts can be marginal as well as major. Variation is to be expected depending on the context. Once we recognise this wide spectrum, we are better able to work within it and design research and trials so that we explore why an impact might vary.

In our third and final article in the series we will present our simple two-step strategic framework to help you assess any context – in order to define the opportunity and manage expectations, and outline how to optimise behavioural science concepts based on your existing deep contextual understanding.

Part three of our series will be published on 13/11/2023

Written by Crawford Hollingworth, Liz Barker and Lucy Pilling - The Behavioural Architects