No, it’s not.

We were delighted to be invited to speak at the launch of Eat Your Greens, a compendium clarion call for evidence-based marketing that we contributed to, in Amsterdam.

It was in a church and we were billed as ‘heretics’ because the principle thesis of the book is that marketers have for too long been guided by strongly held beliefs that are based on myths. Since there is no requirement for any formal education in marketing or advertising, an executive will gradually build a grab bag of anecdotes and framing metaphors that often have little relation to how brand communication actually works. These are used to argue in endless meeting rooms, as opinions jostle with egos, edging out evidence.

One way to understand the polarized dynamics of the advertising industry is through the lens of one of its most canonical — and naive — binaries. Is advertising an art or a science? This debate continues to rage endlessly in the trade press, on Twitter and in the aforementioned meetings.

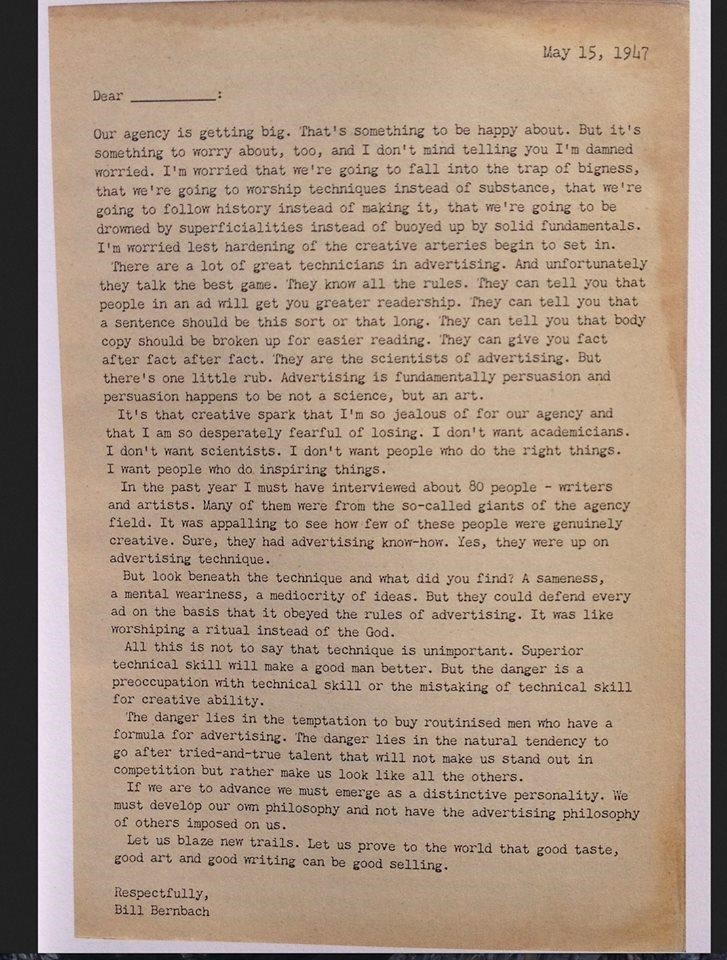

The art argument is most usually expressed in the words of Bill Bernbach, traced back to a memo he wrote at in 1947, in which he rails against advertising ‘technicians’.

“Advertising is fundamentally persuasion and persuasion happens to be not a science, but an art.”

What did Bernbach mean and what was he trying to achieve? When art was cleaved from science and placed in the rarified air of galleries, it became a question of power and authorship.

Who decides what is art and who gets to make it?

Our modern conception, to borrow from Tolstoy, is about self-expression, the transmission of a personal feeling to another person through media. By this modern definition, we can immediately dismiss advertising as art, because advertising can never be self-expression. Advertising is ghostwriting for brands.

However, if things were that simple that wouldn’t be interesting.

Consciously or not, Bernbach was quoting Aristotle, who wrote the first treatise on persuasion, the Ars Rhetorica — [literally from the Latin] “the art of rhetoric [persuasive speech]”. Things are complicated because ‘art’ in Latin meant something worthy of systemic study, more akin to ‘technique’ today. The Greek word for art was techne from which we get technique. The Art of War, sacred text of MBA strategists, is about the technique of war, not about how it beautifully expressed personal feelings.

Whenever a CEO makes a statement publicly and persistently, it should be understood as salesmanship. Bernbach founded DDB and ushered in the creative revolution with this conflation of advertising and art. The end of the memo explains his objectives:

“If we are to advance we must emerge as a distinctive personality. We must develop our own philosophy and not have the advertising philosophy of others imposed on us. Let us blaze new trails. Let us prove to the world that good taste, good art, and good writing can be good selling.”

Whilst written at Grey, it is the founding thesis of DDB.

It was a positioning statement for his agency that came with benefits. The market was still in thrall to Claude Hopkins’ Scientific Advertising and pivoting to art gave the agency, and especially the creative director, the power of the artist, which is the imposition of subjectivity. Artists argue from their gut and creatives still use this to support their opinions against all research and evidence. [Pro tip: when they start a sentence ‘as a creative’ that’s what they are doing.]

Agencies still bounce between these poles. Marketing as science offers the possibility of prediction, without room for the sublime or startlingly fresh. Advertising as art embraces creativity but abandons rigor. Advertising is neither. It draws from both but must also factor in the messy unpredictability of humanity.

Humans are irrational, which is the foundation of behavioral economics. One of the most robust findings in psychology is known as the Backfire Effect, which is important when it comes to having an evidence-based marketing conversation with your agency or client. When your beliefs are challenged by indisputable evidence, you would assume that you would change your mind. Instead, it backfires and you hold to the beliefs more strongly, especially if it concerns something you feel strongly about. Despite overwhelming evidence, increasing numbers of people are not vaccinating their children, don’t believe in climate change, and think the earth is flat [yes, really].

As Seth Godin wrote: “Here’s the conversation that needs to happen before we invest a lot of time in evidence-based marketing in the face of skepticism: ‘What evidence would you need to see in order to change your mind?’

If the honest answer is, ‘well, actually, there’s nothing you could show me that would change my mind’, you’ve just saved everyone a lot of time.”

As rationalists we believe that marketing decisions should be based on evidence but as communicators we know that facts don’t change minds. The challenge is in how to market the evidence — to both audiences and agencies — and Eat Your Greens is our attempt.

This piece by Faris appeared on Medium.