In the UK, most of the population lives in urban areas.

In fact, in 2014, 74% of people lived in an urban area, the highest in the OECD. In Australia too, it’s high, at 70%. Across the whole OECD, the figure still stands at 46%. Given that cities and towns are home to most of us, it’s clear we need good urban design to generate the best quality of life. This article looks at how one company is working to leverage behavioural insights to design better cities and public spaces which celebrate how people and communities live, work and play.

These insights could facilitate mass behaviour change in cities all over the world.

How pedestrians have been squeezed out by the car

Over the past few decades, cities have been designed for cars, not people, leading to poor and even unsafe experiences for city dwellers. Cities and urban areas are still, as the esteemed Danish architect Jan Gehl (pictured) says, the “product of the traffic engineers’ heyday”. Often, the ratio of space for cars versus people is completely out of balance.

For example, research by Gehl in New York City’s Times Square, found that 90% of the available space was allocated to cars whilst 90% of the people were pedestrians.

City planners know a striking amount about cars in their city and do a great job of monitoring and collecting statistics on traffic flows, parking spaces and driving violations, but Gehl has found, they tend to do a really poor job of gathering behavioural data on pedestrians. They know very little about when, how and where their city dwellers are moving, what they are doing and what they would like to do. Poor design of urban space can also confine people and encourage them to use their cars to get around, rather than walking or using public transport. In an era of multiple health crises linked to a lack of physical activity, it’s even more important to encourage people to use their own two feet and urban design has to incorporate this imperative.

Using behavioural insights for effective urban design

Frustrated with the misaligned focus on the car and spurred by his psychologist wife who asked why architects didn’t try to understand people as well as buildings, Gehl formed Gehl Architects to specialise in the design of public spaces in urban areas. Their novel approach makes them literal behavioural architects! It also bears some similarity to the thinking of Jane Jacobs, author of 1961 book “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”, who was a much earlier proponent of humane urban planning.

It was she who said, “Not TV or illegal drugs but the automobile has been the chief destroyer of American communities.”

By combining insights and understanding from the social and behavioural sciences with an expertise in architecture and design, they set out to understand human behaviour in a particular space, delving into people’s use of public spaces, asking questions such as:

- How are people using their environments?

- Where are they spending time?

- How do these environments contribute to their quality of life and lifestyle?

- Where are they walking, sitting, playing or even lying down (if the weather is nice)?

- Who is moving around? - Is it only one demographic, or is it varied, including the elderly and young children?

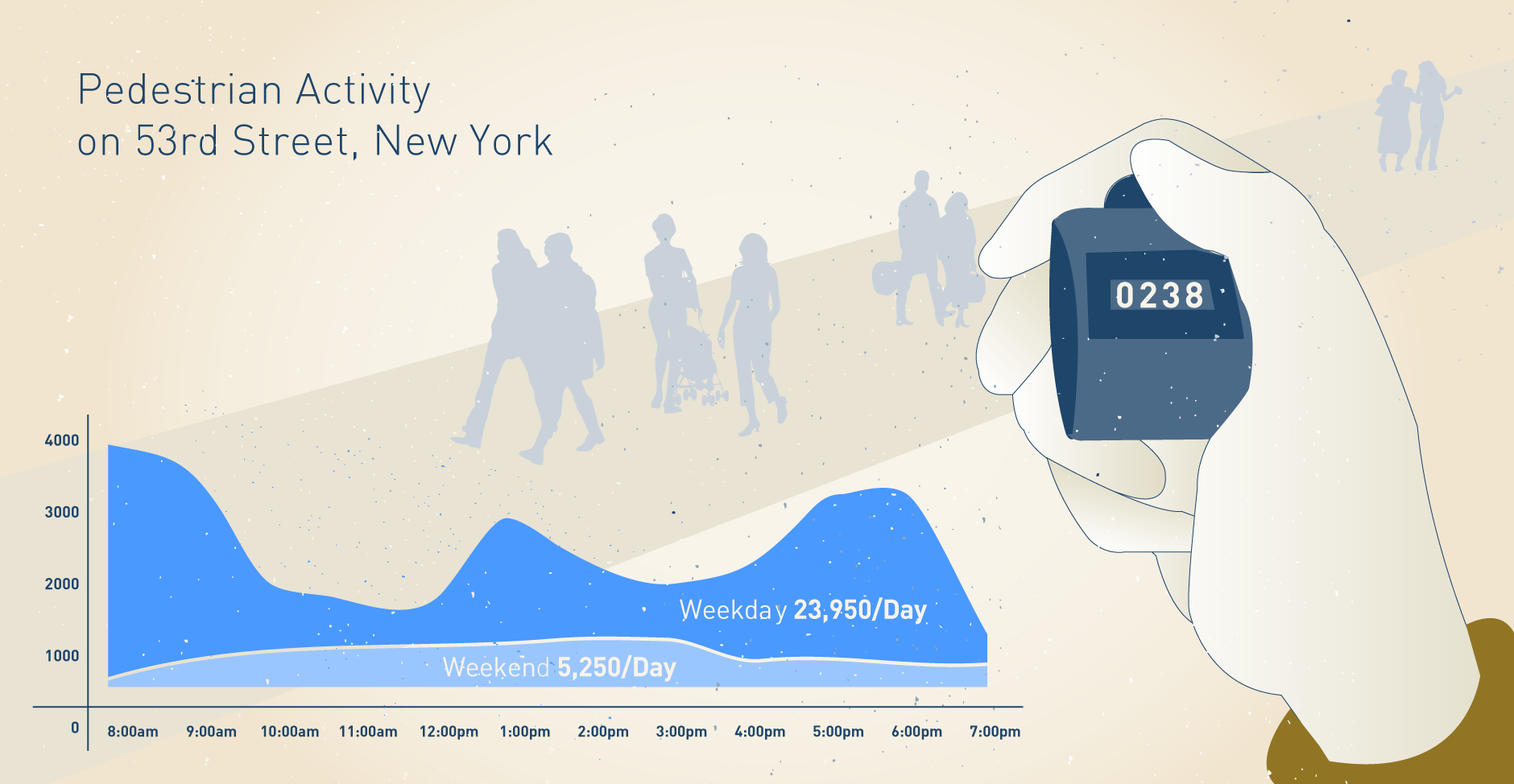

They use ethnographic techniques to observe behaviour at all times of day during the week and weekends, counting how many men, women, children of all ages pass by and what routes they take, where they linger, sit down, what places they avoid etc. For example, see the chart below plotting pedestrian activity over the course of a day on 53rd Street, New York City.

Source: Gehl Architects

Their observations there revealed that only 10% of pedestrians were children or elderly, even though these groups make up 30% of the city’s population. One thing they’ve come to understand is that low numbers of the young and old is a key indicator of a public space that is failing to meet the needs of its citizens.

They take note of where people jaywalk, how long the wait is at traffic lights (in Sydney’s George St they found that wait times could be as much as 52% of the walk time between two places), the areas and streets they avoid, and what obstacles they have to negotiate. They track the literal behavioural journey of urban dwellers. Noting that people automatically tend to take the easiest or most attractive route rather than the designated route, Gehl’s team analyses the factors which contribute to attractiveness and ease of movement: the position of and number of bins, the tactile surfaces of pavements, the availability of seating areas, fear of or threat of crime and insecurity, lighting levels and the need for lighting, and even if wind funnels through certain areas and how and where natural light and sunlight falls through the day.

They also analyse “visual pollution” from road signage, since too many signs can be overwhelming. We tend to notice what stands out and is most salient, but if there is too much clutter - too much trying to grab our attention - our eyes won’t be drawn to anything in particular and we’ll experience information overload.

They also focus on the spaces most salient to the human eye. We all know of choice architecture in the supermarket aisles where we tend to be drawn to the products at or around eye level. Urban design for movement works in a similar way, so Gehl’s team observe and note what is in view at ground level on the street (that’s 72 degrees from eye level).

This approach has generated unique insights which have been used to facilitate mass behaviour change in cities all over the world. Gehl notes that by “looking closely at what people were doing, we were able to identify certain factors that determined their behavior and interactions. We were able to prove over many years that every expansion of the pedestrian system brought more people and more seats and more entertainment and more culture. For example, we found that for every extra 14 square meters of car-free space, you got another person participating in public life.”

They’ve now worked in numerous cities around the world - including Copenhagen – one of the most forward-thinking cities and early movers, Moscow, Los Angeles, Brighton, Sydney, Southampton, Mexico City, New York City, Stockholm, Perth and Sofia. They use the behavioural insights they collect to improve the ‘choice architecture’ in a public space - making it easier for pedestrians to move around, making spaces more enticing to linger in by creating positive affect, making them attractive to the eye or touch, removing threats, or priming an activity or mood.

Bringing life back to New Road in Brighton

In Brighton in 2007, for example, Gehl Architects redesigned the New Road area, in the heart of the city one block back from the beachfront. It had become a run-down backwater, a hub of anti-social behaviour, with something of a no-go feel to it, where people with drug problems tended to hang out. It was a very wide street, where cars were prioritised so that there was virtually no pedestrian activity, especially in the evening, when poor lighting and perceived threat were also a discouragement.

New Road, Brighton before it was redesigned, where the car is forefront to the design

To get a better understanding of how the street was being used, the team collected information on who used the area, how and when they moved in and out of the street, generating a comprehensive pedestrian movement map.

They also interviewed locals, traders associations, councillors and the varied cultural institutions in the area to understand their current use of the shops, restaurants, theatres and gardens; to identify the different types of activity in the street as well as people’s aspirations for the area. Because shop owners on the street were worried about losing business if the street was completely pedestrianised, the team agreed to make it a shared space, but one which prioritised pedestrians over cars.

They resurfaced the entire street with natural stone (granite), removing the cues which we automatically associate with the car - the kerbs, crossings and road signs - to leave no delineation between the pavements and roadway. To prime people to linger and make it easier to spend leisure time there, they replaced the car parking spaces with a carefully honed, long wooden bench looking onto the edge of the Pavilion gardens which backed onto the street. To further prime the context to convey positive feelings of relaxation and encourage lingering and appreciation of surroundings they cut back the trees in the park so that the iconic Brighton Pavilion buildings could be seen from the street.

Uniquely, they also consulted the Guide Dogs for the Blind Association, not only to ensure the redesign met the needs of the visually impaired, but also to use the same sensory techniques which facilitate their mobility, to move and channel people through the space, for instance drawing on tactile guidance strips to mark the edge of the street and textured paving areas to mark thresholds (e.g. to shops) and potential hazards. This generates unconscious, sensory feedback to guide pedestrians smoothly through the street.

Noting that the street, which houses a number of theatres, had potential for evening socialising, they also redesigned the lighting to be warm and bright so that it felt welcoming and safe, even working with a lighting artist to build tiny lights into the wooden bench to make it feel warmer and encourage people to linger.

New Road, Brighton, redesigned

Then they trained city staff to quantitatively assess and track pedestrian movement, so they could measure the sustained impact of the redesigns and analyse and document how people were using new spaces.

A survey carried out in 2008, just one year after the road reopened, showed that traffic levels had dropped by 93%, the number of pedestrians had risen by 162%, and cycling had risen by 22%.

Importantly, there had been a huge uplift - 600% - in people lingering, socialising and enjoying the area.

Surveys of the street pre-renovation found little to no activity, but in 2008 a survey at 10am, 1pm, 4pm and 8pm, captured 500 ‘staying activities’. By 2010 New Road was the fourth most visited place in the city. People now enjoy spending time there. The shared space for cars and pedestrians also appears to have been a success. Monitoring of cars on New Road showed that they drove at extremely low speeds, and very tentatively. The project went on to win no less than four awards in urban design.

The redesigned New Road in Brighton.

Other progressive cities are also making steps to claim back space for pedestrians from the car:

- In Madrid, 24 of the city’s busiest streets have been redesigned for pedestrians and urban parks will be linked in a network which prioritises pedestrians, followed by public transport, bikes and, finally, cars.

- In an attempt to diminish city centre pollution, Milan rewards those who leave their cars at home with a free voucher for bus or train travel – an internet connected dashboard box keeps track of the car’s location.

- Hamburg, like Madrid, is developing a green network across the city, with the aim of making it possible to walk or bike anywhere.

- And a new satellite city planned in SW China near Chengdu, has a layout which has been designed so that any location can be reached on foot in 15 minutes.

Conclusion

You could argue that for years much of the emphasis of architecture and urban design in cities has been anti-people - benches that are hard to sit on and which discourage the lingering and even lying down, which Gehl identifies as important, the removal of public toilets, a dearth of pedestrian areas and, above all, a focus on the car.

In this context Gehl’s clever behavioural work looking at human movement and identifying simple ways to enhance city living for people is deeply refreshing. The ability of small changes to begin to humanise the concrete jungles in which we live gives us at The Behavioural Architects huge hope. Let us not forget that cities are where people come together, where communities need to thrive, where we can grow in all dimensions of our lives. Cities had begun not to function in this way – time to take back the city for the community. How can we ensure there is a human champion in city development, a spokesperson to lobby for the resident? And we now have affordable housing quotas, so why not a quota for enough human friendly, car free space?

In 2018 cities are changing, both their business and social roles are in flux and there is, therefore, no better time for us to ‘re- architect’ cities which understand human behaviour in order to put people first and build stronger societies as a result.

How BE is transforming our lives 24/7 series - article 10

Behavioural economics (BE) is still a buzzword in many sectors, even after breaking into mainstream thinking several years ago and making a significant difference to our everyday lives.

In something of a salute to this, we are running a series of articles over the next 12 months to take our readers on a 360 degree tour of how behavioural science is transforming our lives 24/7; how it is shaping better outcomes for us, enhancing communications, increasing our engagement and response rates and making us healthier and better off.

Each part of the series will zoom in on a particular area or sector.

Sources

https://www.siemens.com/customer-magazine/en/home/specials/taking-the-measure-of-the-city/jan-gehl-a-passion-for-the-livable-city.html

http://gehlpeople.com/cases/new-york-usa/

http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-economic-surveys-united-kingdom-2017/percentage-of-uk-population-living-in-urban-areas-is-the-highest-in-the-oecd_eco_surveys-gbr-2017-graph53-en