Many of us have a tendency to focus on today’s financial needs, and bury our heads in the sand when it comes to thinking about saving, particularly for retirement. That time of life can seem such a long way off, whilst in the present moment there are seemingly so many pressing demands on our money: a new car, house maintenance and improvements, as well as annual holidays and even Christmas presents for the children.

Compounding this problem is our tendency to hope for the best and optimistically believe we’ll earn more money in the future, or even that ‘it’ll all work out in the end’. We also struggle to imagine our future selves - an effect known as the ‘end of history illusion’ - meaning that we may find it difficult to plan for the future because we don’t feel we will change or have different needs from the ones we have now.

On top of this, financial products can be complex and, understandably, people struggle to make sense of them, often losing concentration and switching off. The latest statement is consigned to a pile of unread notifications and emails are left unopened.

Why the ‘Autopilot’ approach may not be enough

Whilst some ‘autopilot’ initiatives such as auto-enrolment and auto-escalation in retirement savings - inspired by insights from behavioural science - have certainly had huge impacts and made leaps forward in basic participation in savings schemes, they ask nothing from individuals in terms of engagement.

This type of approach leverages what is known in behavioural science as a ‘System 1’ approach – when behaviour change is achieved by relying on our tendency towards inertia and settling for the status quo, and for choices and selections that require the least effort in both thought and action on our part.

In this scenario, an individual could be auto-enrolled into a pension in their current job, accept the default fund(s) and the default contribution rate (currently 2% in the UK, but increasing over time to an eventual 8% in 2019), but have very little understanding or engagement with their pension. Individuals might not even remember they are enrolled in a pension plan, let alone think about how to optimise it for their needs. And not consciously choosing to do something can result in a lower level of commitment and responsibility or ownership.

In the US, this lack of engagement also means that people are cashing out their retirement savings, not understanding how vital it is to keep these savings untouched. One in four households with a defined contribution fund cashes-out its savings, meaning that as much as $70 billion is withdrawn from 401(k)s on an annual basis.

Jonathan Rowson of the RSA summarises the issue succinctly: “Nudge changes the environment in such a way that people change their behaviour, but it doesn’t change people at any deeper level in terms of attitudes, values, motivations etc.” He and other social scientists still see the need for a more conscious, thoughtful engagement, which aims to “foster the transformative learning we need to make significant and enduring changes to our behaviour.”

With this in mind, some behavioural scientists and practitioners have been looking at ways to build greater and more sustained financial engagement with employees, so that they become more capable of managing their money for the future. This approach draws more on employees’ ‘System 2’ - their logical, rational thinking style - looking at how we might get them to consciously reflect on how they should best save for their future.

In this article, we discuss four simple, yet effective approaches that are building greater engagement with our finances, so that we are sufficiently prepared for the future. None involve any radical, costly changes - they are just tiny tweaks in how and when information is presented. Yet, all of them show promise.

Keeping people’s attention by asking less of it

One seemingly counter-intuitive approach proposed by a financial company called Hellowallet may increase levels of engagement by engaging with people less often, demanding less of their time and cognitive energy.

Hellowallet is a relatively young company based in the US, which puts behavioural economics at the heart of what they do. It provides a web and mobile platform to Fortune 100 companies, which brings together each employee’s financial accounts into one place for them to access. It also provides personalised financial guidance to enable better money management and to increase financial well-being.

Using the Hellowallet platform, they recently tested this theory in a series of randomised controlled trials with thousands of their clients’ employees.

Their standard approach had been to send platform users a weekly Friday email containing a summary of their finances, aimed at encouraging them to control their spending, build their financial literacy, begin to understand compound interest, build a budget, set up regular savings debits, etc. Yet, they wondered whether they might increase engagement if they expected less of users and contacted them on a less frequent basis. To test this hypothesis, they selected one group of employees registered to use the Hellowallet platform to receive the summary email every other week.

They found that asking for employees’ attention on a less frequent basis resulted in greater engagement over the long term. After 90 days, the open rate for bi-monthly emails was 65% compared to 58% for weekly emails, a 7 percentage point lift. Click-through rates also increased from 23% to 29%. Their strategy of not inundating and overwhelming employees with communications paid off, with higher levels of sustained engagement in the long run. Whilst it’s a small step, tiny adjustments like this can start to add up to increased engagement over time.

Effective communication can also be just about finding a good moment to engage with people. Talk to them when you might be able to get their undivided attention and fit learning around the time that people have. Samsung have been working with Nudge Global - a financial education company - to improve financial wellness among their employees. One of their initiatives has been ‘Learn in the loo’ - putting simple financial education content in the staff toilets where there is a greater opportunity to get someone’s attention.

Increasing cognitive ease to increase engagement

Sometimes, it’s not the frequency of information, but the sheer amount of it that can create a barrier to action. LV= and The Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) recently tested an approach which focused on getting people’s attention by including a simple one-page, ‘go-to’ summary inside a large pack of information.

In the UK, those approaching retirement are no longer required to purchase an annuity, but instead can take out a cash lump sum. These are complex choices and experts recommend that people seek financial guidance before making any decision.

Therefore, people in the UK can access free and impartial guidance via the UK’s Pension Wise service. Those approaching retirement age are notified of the Pension Wise service through a signposting letter included in the standard wake-up information pack. However, these ‘wake-up’ packs often contain over 100 pages of dense, complex information, leading most retirees to feel overwhelmed and switch off rather than ‘wake up’.

Therefore, people in the UK can access free and impartial guidance via the UK’s Pension Wise service. Those approaching retirement age are notified of the Pension Wise service through a signposting letter included in the standard wake-up information pack. However, these ‘wake-up’ packs often contain over 100 pages of dense, complex information, leading most retirees to feel overwhelmed and switch off rather than ‘wake up’.

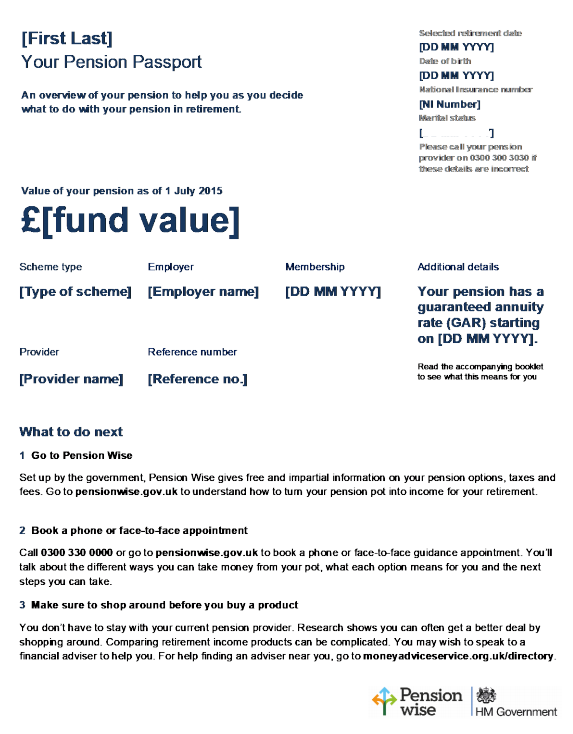

To address this problem, the BIT consolidated the vital information in LV=’s pack into a single A4 sheet (see image), reducing the total amount of information customers have to digest, and making the most important information more salient, including making the next steps to take clear.

The initiative had a significant impact, lifting the number of visits to the Pension Wise website from around 1% to almost 11%, and also increasing the proportion of customer calls to the service, from 5% to over 8%. Whilst response rates ideally need to be much higher than this, it’s a promising start.

Change the frame to change a mindset

Whilst it’s tough enough managing your money as an employee, the self-employed have an even harder deal. Being self-employed can often make managing money much more complex. Income can be unpredictable, careful tax planning is required, and retirement savings and health insurance need to be organised and planned for. Many do not save enough money for either. In the US, 10% of US workers are self-employed and in the UK the figure is 15%.

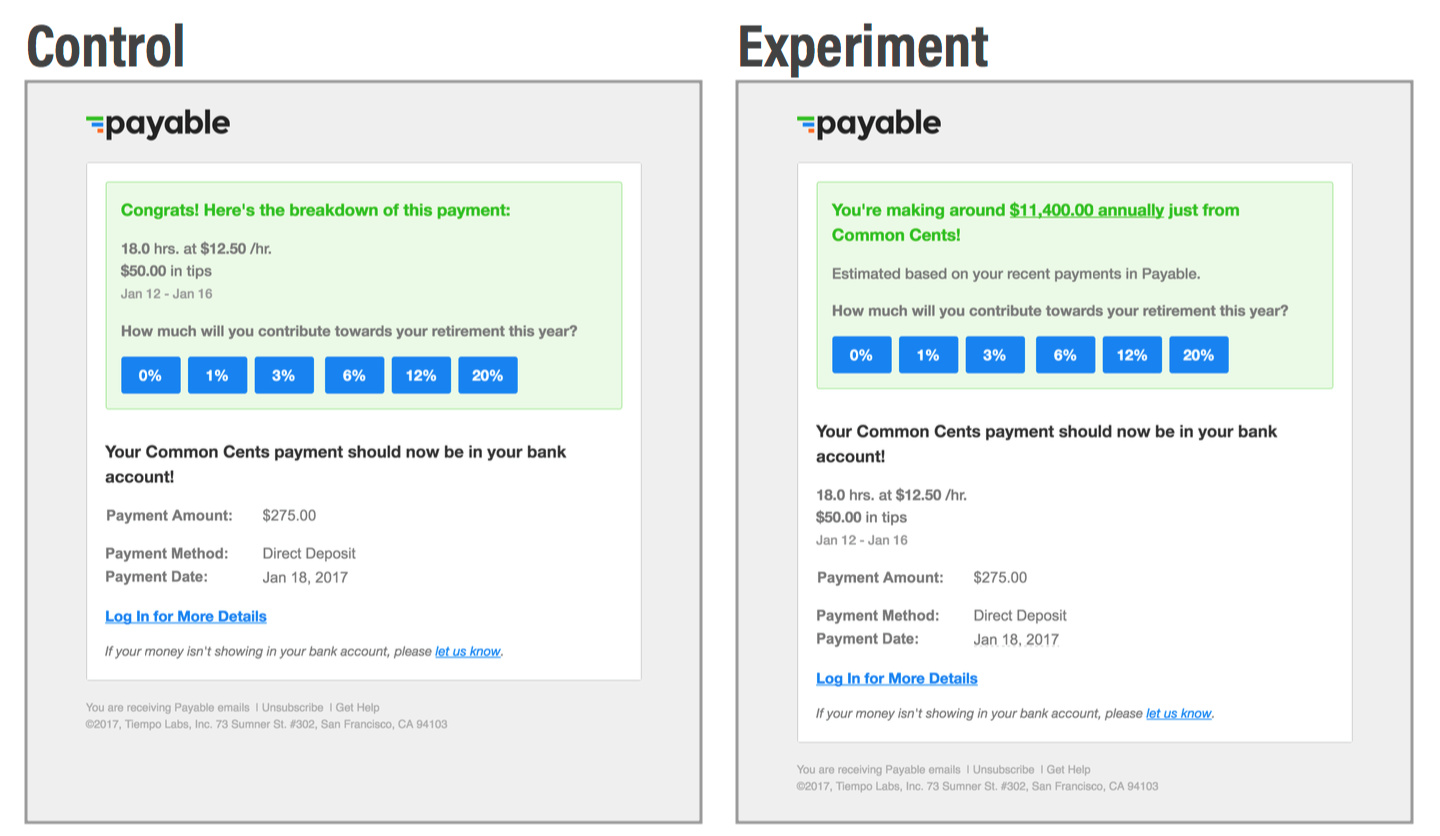

To help solve this problem, Dan Ariely’s Common Cents Lab at Duke University partnered with Payable to encourage more self-employed people to open a retirement savings account. Payable helps tens of thousands of self-employed people get paid faster and more efficiently by making invoicing and work-tracking simple.

They used a simple A/B email to test if displaying someone’s income in annual terms, instead of “per job,” would increase their likelihood of signing up for a retirement account. This reframed people’s income to encourage a long-term mindset.

Reframing income into an annual form increased the number of people who clicked through to start saving for retirement with a third-party by 14.5%. Encouragingly, most of the 1099 people signing up indicated that they wanted to save 12% to 20% of their income.

Reframing information to increase comprehension and action

The Behavioural Architects have also drawn on the technique of reframing pensions information to make it more meaningful and encourage action. We worked with a large financial services company to redesign the annual statement for retirement savings accounts. These are typically very dry, complex and poorly presented documents. Merryn Somerset Webb, editor of the personal finance publication Moneyweek recently commented:

“I used to have a workplace pension with Standard Life. It was awful. I got a letter every year with a “plan summary” on it. It told me last year’s value, this year’s value and the amount added into my plan over the year.”

For most people, these numbers are pretty meaningless and can also lead to what behavioural scientists call ‘illusion of wealth’ effects - thinking we have saved more than we really have prompted by seeing the value of the lump sum saved so far. It can lead us to feel ‘rich’ and overconfident about having saved enough for retirement. A lump sum of £100,000 can seem like a lot to someone mid-career, earning an average salary, and may encourage them to rest on their laurels, but it is nowhere near enough to fund a retirement.

Research carried out by behavioural scientists Shlomo Benartzi, Hal Hershfield and Dan Goldstein tested ways to counter this effect in a small field experiment run in conjunction with a financial advisory firm. Financial advisers phoned 139 of their clients and told them how much money they had saved - either as a lump sum or in terms of what that sum would roughly equate to as their projected monthly income in retirement. They then asked them if they would like to change their current savings rate and if so, what that new rate would be. 36% of people who were quoted the monthly income figure opted to increase their savings, compared to only 21% of the lump sum group. In addition, those quoted the monthly income figure increased their savings rate by more than those quoted the lump sum figure.

This finding demonstrates how reframing a lump sum figure into more meaningful numbers, such as monthly income or annual income, can prompt people to increase the amount they are saving. We automatically compare such income figures to our current salary which could help us to realise that we need to save more if we want to maintain a similar standard of living.

Keeping this in mind, we worked with our client to redesign the front sheet of their annual statement so that the lump sum saved so far was also converted into a projected annual income in retirement. For example, rather than a projected lump sum of £200,000 based on current savings and rate of future saving, we displayed it as a £13,000 per annum income in retirement. Enough not to starve, but hardly likely to provide a comfortable standard of living for most. This is the kind of shock trigger that might be necessary to prompt increased engagement with retirement planning.

This and other changes we recommended led our client to be rated in first place (with a score of 7.6 / 10 from an earlier score of 5.8) by an independent ratings agency for pensions information provision.

Conclusion

Although initiatives such as auto-enrolment and auto-escalation are helping to get people saving more towards their retirement, they only solve part of the problem. Initiatives like the ones we’ve outlined above, which help to increase engagement and understanding of savings and investments are essential.

Think about the time you are demanding of people and when you are asking them. Think about whether the information is easy to access and simple to understand. Think about different ways you might frame the same information or what reference points might aid understanding and comprehension. These powerful insights can help radically change how we all think about our money, so we can plan better for the future.

How BE is transforming our lives 24/7 series - article 6

Behavioural economics (BE) is still a buzzword in many sectors, even after breaking into mainstream thinking several years ago and making a significant difference to our everyday lives.

In something of a salute to this, we are running a series of articles over the next 12 months to take our readers on a 360 degree tour of how behavioural science is transforming our lives 24/7; how it is shaping better outcomes for us, enhancing communications, increasing our engagement and response rates and making us healthier and better off.

Each part of the series will zoom in on a particular area or sector.