Ask someone if they know what ‘nudge’ means, and they’re increasingly likely to answer ‘yes’. ‘

Nudge’ has become a watch word of behavioural science and is widely understood as being indicative of actions which steer behaviour change. But are people as familiar with the related term ‘sludge’?

Perhaps not, not yet, but they would be well advised to get up to speed. ‘Sludge’ has come to represent the dark side of nudge ethics and is used to define and draw attention to companies who use behavioural science and nudges in ways that hurt rather than promote the welfare of consumers. Sludging includes things like hidden add-ons, or long and confusing fine print, hidden subscriptions, or bureaucratic red tape and paperwork. In short, sludge is any measure which makes it harder for a consumer to do what’s in their best interest.

Sludge was defined by Richard Thaler, this year’s Nobel Laureate, who, together with Cass Sunstein, also coined the term ‘nudge’. It highlights how companies can and are taking advantage of innate consumer traits and fallibilities such as inertia and inattention, knowing that they can profit off the back of consumers’ weaknesses and biases.

Thankfully, regulators and other organisations are realising the need to monitor, minimise or even stop these sorts of practices - acting as a type of ‘BE Police’ to protect consumers from a potentially deluging ‘behavioural goldrush’. This is a whole new radical approach, since previously regulators have tended to rely on the concept of full disclosure and assume that, as long as companies provide full terms and conditions for a product or service, consumers are protected from wrong-doing. Behavioural science has demonstrated why that wasn’t sufficient and has offered an alternative that has recognised consumer biases and fallibilities.

This policing role has two types of remit:

- The detective – Here regulators are investigating and uncovering where companies might be using unethical practices to nudge suboptimal behaviour among their customers. In doing so, they are making consumers more conscious and aware of the ways in which they may be taken advantage of.

- The lawmaker - Where companies and institutions are exploiting unintentional consumer errors (prompted by innate biases), regulators and other institutions are using behavioural science first as an analytical framework and then to inform guidelines and rules or design new policies or laws to ensure these errors can’t occur. Further, behavioural science is helping regulators to understand consumer biases and adapt industry regulations to take account of them.

This article delves into these two types of ‘BE policing’, showcasing several recent case studies from regulators all over the world.

The detective

One area regulators are focusing on is subscription traps - free trials with complex or unclear subscription processes or automatic renewals.

These are common across a wide number of sectors, including healthcare and technology, particularly those online. We’ve all signed up for a service or product not realising what payment schedules we are committing to, or taking advantage of a short term free trial which we’ve then forgotten to cancel.

Behavioural science can help to analyse how these sorts of traps take advantage of consumer fallibilities. Experiments run by the EC in 2016 found that when [an attractive] price is very prominent, consumers tend to be distracted from subscription fees so they are not aware they are signing up to anything (a lack of salience). Consumers also commonly suffer from overconfidence, thinking that they will remember to cancel a free trial / subscription in one, two, three months’ time, but when that time comes, forget.

Further research revealed that over 97% of the offers screened used a misleading practice and half of the free trials and subscriptions included five problematic practices such as poor clarity around subscriptions and trials, particularly in the case of cosmetics and healthcare products.

In the UK, the problem is common too. To try to curb this, Chancellor Philip Hammond announced plans in the March 2017 budget to make subscription terms clearer and included proposals to prevent “unexpected payments”, which could include stopping companies from taking payment details when customers sign up for a free trial. He also handed regulators greater power to fine companies in breach of these standards.

The new legislation is aimed primarily at mobile phone providers, online shops, banks and other financial institutions. Firms will now need to briefly summarise the key points of their terms and conditions in prominently displayed bullet-points or face being named and shamed in league tables of bad practice. Firms will also be banned from taking customers' card details for free trials.

The UK’s Competition & Markets Authority (CMA) has also been conducting industry investigations grounded in behavioural science.

- For example, in the airline industry, they are aware of the effects of ‘drip pricing’, where consumers are initially attracted to the headline price and then under-estimate the cost of ‘add-ons’. In 2012, concerns about this led the CMA to take action on some airline payment surcharges (typically only revealed at the end of the online booking process).

- They have also restricted the number of energy tariffs a consumer will be offered, aware that information overload or too many options can often lead to confusion, decision-fatigue and ultimately poor choices.

- Large discounts in price are extremely attractive since we feel we’re getting a good deal and retailers have long exploited the consumer tendency to anchor on price. Industry research by the CMA found that some sectors, such as furniture retailers, were advertising false discounts based on RRPs which had not been previously been sustained.

More recently, the CMA announced a new investigation into hotel booking sites, questioning whether ‘sludge’ techniques are being used here. I’m sure you’ve all seen those hover messages that flag up on booking sites during your search, saying things like “Only 2 rooms left!” or “10 people looking at this room / hotel right now!”. These techniques, known as pressure selling, leverage concepts from behavioural economics such as scarcity bias (being attracted to something in short supply) and social norms (when we conform to what others are doing or have done before us).

The CMA are concerned whether these types of messages create a false impression about the availability of a room, causing consumers to rush to book. Like the furniture retail investigation above, they are also looking to discover if booking sites use false discount claims, hidden charges and if search results are ordered in a way that prioritises consumer preferences or are, in fact, driven by commission-based earnings.

The lawmaker

The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority adopted a regulatory approach leveraging behavioural economics back in 2013 and have not only conducted investigations on this basis, but also designed new policies around it.

For example, an investigation into general insurance add-ons led to policy action based on their findings. Insurance add-ons for products and services such as gadgets, travel, cars and homeware (boilers and gas appliances and the like) are defined as insurance products people purchase alongside other products or services, in contrast to ‘stand-alone’ products such as a separate insurance contract, independent of any other purchase of another product or service.

After carrying out both quantitative and qualitative consumer research and a behavioural experiment to test consumers’ reactions to the add-on mechanism in a simulated environment, the FCA concluded that add-ons were harmful to consumers.

They felt that when products are bundled in this way it is difficult for consumers to understand the overall cost and value of the product presented to them.

In 2015 they banned the opt-out selling (i.e. via pre-ticked boxes) of these products across financial services and stipulated that add-ons be introduced early on in the consumer journey / sales process, so consumers are aware of these additional - yet optional - costs as they compare options and reach a decision.

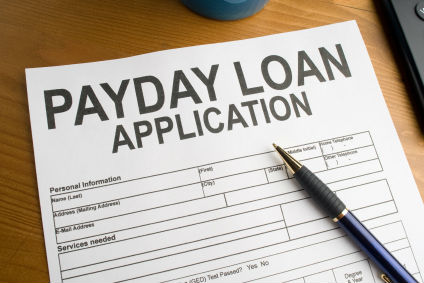

The FCA also took action to curb payday loans, a market that had grown rapidly due to new online lenders, where lenders were charging extremely high interest rates for short-term loans. After rigorous quantitative analysis and a review through a behavioural science lens - which concluded that consumers were being exploited by payday lenders - they took regulatory action. In January 2015 they introduced a cap on interest rates charged by payday lenders. Rates could be no more than 0.8% per day, with a further stipulation that no more than 100% of the initial loan could be repaid.

Following the introduction of the caps, the number of loans dropped from a rate of 800,000 a month, to about 300,000 a month in 2015. Since then lead lenders such as Wonga have seen their business shrink and Money Shop, another market leader, has been put up for sale.

On the other side of the world, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Australian equivalent of the FCA, have also been leveraging behavioural science to inform the shape of new regulation and policy. For example, aware that consumers suffer from inertia, tend to ‘go with the flow’ and generally accept new terms and conditions without detailed analysis, they were concerned that credit card companies were increasing customer credit limits without asking customers if they wanted the limits to be raised. With this in mind they prohibited such unsolicited increases as part of a policy reform.

They also influenced new policy on credit card interest rates after conducting behavioural research into consumer credit card decision-making and behaviour. The insights gleaned informed their submissions to the Parliamentary Inquiry into credit card interest rates and were also reflected in the remedies put forward by the Treasury in response.

Conclusion

Whilst behavioural science is, for the most part, being put to good use across a wide range of sectors and purposes, it can be leveraged to take advantage of consumers. However, in many cases, regulators and other institutions - the ‘BE Police’ - have succeeded in arming themselves with the new tools that behavioural science offers to combat so-called ‘sludge’.

Equipped with an understanding of behavioural economics and the effect of biases on consumers, the BE ‘police’ are able to conduct deep analysis and design more effective policies with protecting consumers as the driving force

How BE is transforming our lives 24/7 series - article 7

Behavioural economics (BE) is still a buzzword in many sectors, even after breaking into mainstream thinking several years ago and making a significant difference to our everyday lives.

In something of a salute to this, we are running a series of articles over the next 12 months to take our readers on a 360 degree tour of how behavioural science is transforming our lives 24/7; how it is shaping better outcomes for us, enhancing communications, increasing our engagement and response rates and making us healthier and better off.

Each part of the series will zoom in on a particular area or sector.

Sources: