Last week one of my colleagues asked a group of predominantly white leaders how comfortable they felt talking about race with their teams. In doing this, she opened up a rich and emotional conversation - uncomfortable, imperfect and crucial.

The team had already been involved in creating company action in response to the murder of George Floyd - action involving a $1m donation and 75,000 hours dedicated to volunteering on Juneteenth, with an educational internal campaign to ensure that this volunteer time will be meaningfully spent.

But this was a subtler thing - a question about the comfort of leaders in their ability to talk about race at all. As the only black woman in the room, It shouldn’t have fallen on her to raise the question.

In September of 2017, I wrote an article called: ‘Why white people urgently need to get better at talking about race’, a build on Renni Eddo Lodge’s original blog post and book ‘Why I’m no longer talking to white people about race’. I’m revisiting some of that article here today to see if it can help others by offering my own experience. I also wanted to relook how I wrote on this topic before - by showing more vulnerability and acknowledging that as a white woman, I have often been part of the problem.

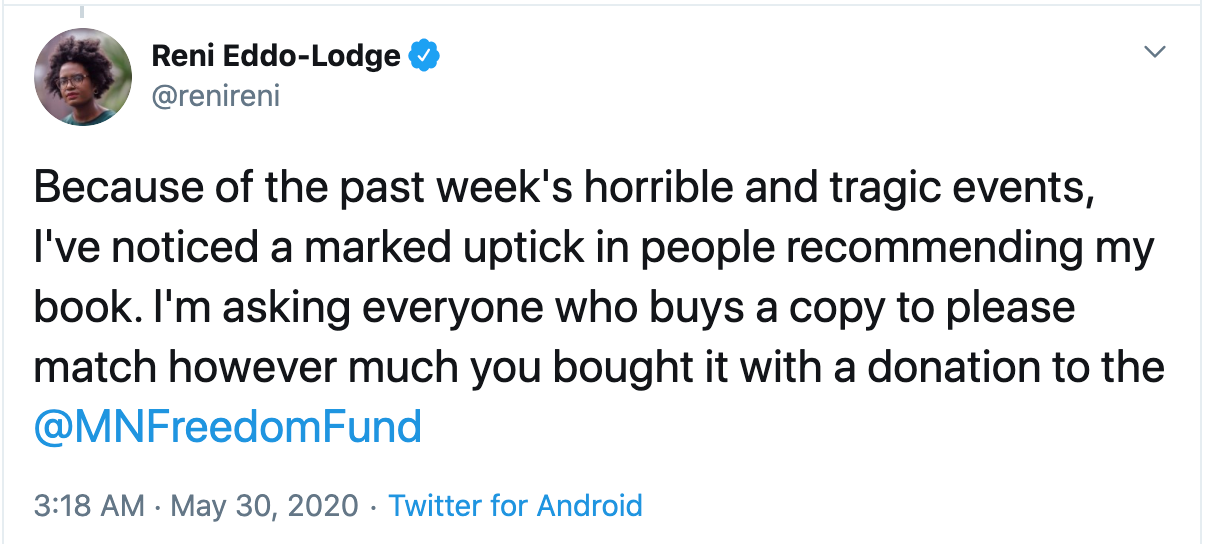

As a quick aside, if you’ve not read Renni’s book, then please take a break from reading this and place your order. Her writing is a beautifully accessible repost to responses like All lives matter, or claims of color-blindness and much more. And if you do order the book, please follow Renni’s request below and match the book amount with a donation to the Minneapolis Freedom Fund.

Today we are seeing a huge rise in optical allyship as the world reacts to this wave of highly visible racist police brutality. The murder of George Floyd has paved the way to broader awareness that this is a daily war on black people, not a one-off event. Rightly there is heightened tension over whether white people forming their first words on this subject have the right to speak up now, and a heated debate on what would give them that right. Is attending the protest enough? Should they make a donation? If they do, how much is enough?

But this movement is about black people’s right to feel safe, respected and heard. Not about white people’s right to anything, let alone the right to speak.

So we have to both listen, and accept the anger of those who say this is too little too late. Because it is. And we have to change the narrative amongst white people asking if they have the right. Because for anyone in a position to drive change, there is a mandate to self-educate, to act and to speak beyond optical allyship. If we can lend influence to shifting the structural racism that surrounds us, then the answer is simple, we must.

And - I’ll say it again - we must be prepared to be criticised for it not being enough. We have to accept and listen to the pain and hurt that we cannot possibly understand without making excuses for ourselves. This resource that I shared yesterday, made by a colleague for sharing, is a great place to start understanding this.

The story I am revisiting is from a less heightened time. A few years ago, as part of my job, I moderated days of debates between white executives and black radio producers on whether to call a radio station ‘the home of black music’, and whether the only BBC station that exists to serve young black people in the UK even had a role. People shouted, someone cried, one person asked why a white person was moderating at all. I apologetically answered, ‘Because I had moderated the ones for the previous stations…’

Did I have the right to be in that role? Probably not. Was the advertising agency I worked for at the time diverse enough to cast a person of color in my role? No. As a relatively junior person, that wasn’t my fault. But I was part of the problem. And I could have done more even by just being more real, more vulnerable and more ready to accept criticism. Looking back, I always could have done more to hold my workplace and myself accountable.

I was talking to a group of young black professionals and the language I was supposed to use, when referring to our audience - who were also young black people, was ‘the BAME youth’. For non-UK readers, BAME is the government approved catch-all for non-white people in the UK. It refers to black, asian and minority ethnic - something which is deeply problematic given that a catch-all like this implies that we can group together the challenges faced by all non-white people, and hide behind acronyms and distanced language that is ‘government approved’ whilst doing so. While I am proud of the work that we did together, I am also deeply embarrassed looking back at these days.

Despite being passionately invested in the project, I wasn’t comfortable from the start. I worried that the language I was using could cause offence. Or worse - that by tackling racial issues, I could be seen to be appropriating struggles that were not my own or as casting myself as a white savior. As a result I often hurriedly mumbled my way past the inclusive acronym BAME - sometimes three or four times in a single sentence. This left me feeling like it was a cop out, putting distance between myself and the group.

Today, there has never been a more pressing need to talk about police killing black men and black women. And to support the Black Lives Matter movement with no catch-alls, no excuses, no corporate distancing or jargon.

The good - but horrendously late - news for those of us who work in marketing, media or entertainment is that inclusion moved from ‘an objective’ to table stakes on May 25th 2020. Now the businesses who ‘champion diverse voices’ must be ready to spend their money on fixing the problem, to support activist causes, to set targets and hold themselves accountable to them. Because we need black leaders to dismantle the structures of white privilege for obvious reasons, and because white leaders will always be partly blind to these structures.

Today, I believe that one thing holding back many businesses is fear. For individuals, part of that fear is about finding the words to say what is needed. Coming back to the story I shared at the beginning. It can’t fall on the shoulders of the only black person in the room to ask the question, ‘Are you comfortable talking about racial injustice?’. It’s not the job of people of color to educate others, or to create more leadership jobs for people of color. This time is forcing a directive for white people to do better, to admit failure, to step aside, to accompany their vocal allyship with actions, personal sacrifices and our money.

As well as acknowledging past failures, looking for more blind spots, speaking up, and adding my voice to my colleague’s, another thing I can do is to build my team right.

But outside of this, I want to do more. For any people of color looking for a career in advertising or marketing - at EA or not - I am here to help. I will review resumes, provide coaching, talk through an application for a role posted on EA or in an advertising agency. And not only at this moment, but always.

Updated from original article published September 2017 in The Marketing Society.