In 2001, Mark Simmonds suffered a mental breakdown, caused by extreme stress in the workplace. He spent four months off work, descending into the depths of a devasting depression, before he tried to take his own life in July of the same year. Without success. In March 2019, he had a book published, called Breakdown and Repair which recounts this episode in detail, both the before, the during and the after.

Every month, Mark will take extracts from his book and identify the key lessons that he would like to share with members of the Marketing Society around specific themes in his book. These themes are all linked in some way or other to mental health in the workplace. By being very open and honest about his experiences, he hopes to do his bit to end the stigma surrounding mental illness and encourage others to share their own stories for the benefit of others.

In this first article, he explores the role of genes in mental health, highlighting the importance of understanding your genetic make-up when deciding which corporate environment is most likely to provide the best fit.

In the world’s largest investigation into the impact of DNA on mental disorders, more than 200 researchers identified 44 gene variants that increase the likelihood of anxiety and depression. I am certainly not a scientist, nor a biologist, and I don’t have the slightest interest in genetics. I was always more into the ‘fluffy’ subjects at school like English and French, rather than the ‘hard as concrete’ ones like Mathematics and the Sciences. But I think I might just have stumbled across two new gene variants to add to the 44.

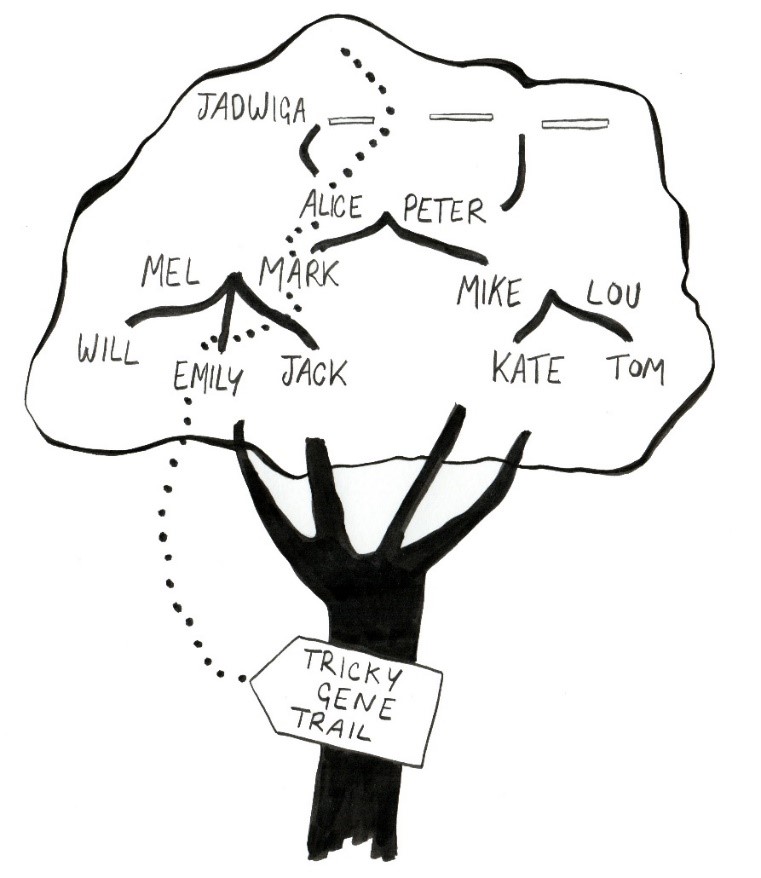

One is called Worry and the other is called Winner. These are what I call ‘tricky’ genes. Having one or the other is generally okay, I think. But when both are deeply embedded in your DNA, it might just lead to some internal conflicts, and fireworks could go off. In the competitive landscape of the business world, this combustion can have serious consequences.

Worry gene

There were undoubtedly some early warning signs during my teenage years that Worry gene was in my blood. At school, I was a very conscientious student. I prepared myself well for exams, never leaving things until the last minute, always heavily dependent on strict and meticulous revision timetables. My peers would be burning the midnight oil, cramming in facts and figures, while I was tucked up in bed at 10pm, fully prepared for the challenges of the next day. This was a sign not of complacency, but one of extreme caution.

My mother, Alice, was the worrier in the family and the permanent creases etched on her face were testament to this. She had three mechanisms for coping with daily stresses. She did her best to avoid any situations that brought uncertainty with them; she smoked like a chimney; and, later in her life, she resorted to a cocktail of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety pills to keep her nerves under control. Life seemed to be one perpetual challenge for Alice. A never-ending struggle.

I think I inherited my Worry gene from my mother. I would pass it on to my daughter, Emily. For all three of us, worrying about things has been a part and parcel of our lives. In my case, it has given me the advantage of being a very careful, conscientious and caring business person, but it has often prevented me from having the resilience to deal with the daily uncertainty of the corporate world. The 2018 UK Workplace Stress Survey reported that work was the most common cause of stress for UK adults, with 59% experiencing it. My Worry gene was always going to be in good company in the business world.

Winner gene

One of my other core personality traits was that I was always a very competitive person, academically, socially, and in the sporting arena. I was blessed with above average talent in several different team sports at school, including rugby and cricket, and competing and winning have always been important to me. I am not sure whether my aptitude for sport or my desire to win were a result of either nature or nurture. I suspect it was both.

So, not only was I burdened with the Worry gene, but I was also ‘blessed’ with a very determined and ambitious ‘Winner’ gene, the other tricky twin.

Unfortunately, these two, side by side as they were, did not always make for compatible partners. There were too many fundamental differences between them, in terms of what they valued and what they felt to be important.

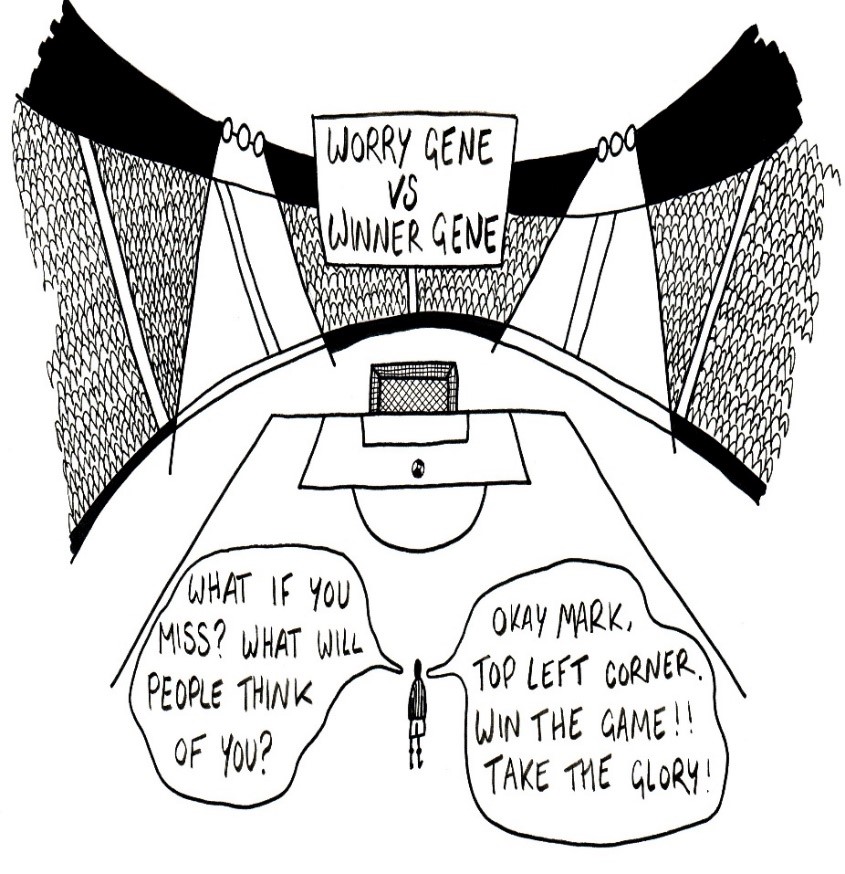

My high levels of anxiety and my inability to relax when under pressure meant I never quite fulfilled my potential, in particular on the sports field. I was occasionally let down by my mental fragility because I cared too much about losing and disappointing others.

When my mind needed to be relaxed and focused in the heat of battle, it was often infiltrated with negative thoughts and irrational doubts, neither of which were conducive to the art of winning.

I would not have been the person to take the last-minute penalty to win the football World Cup final, serve out for the match in a tense fifth set in the Men’s final at Wimbledon or sink a difficult downhill 10-foot putt to win the US Masters Golf Tournament at Augusta.

There would have been far too much distracting noise in my head. Winner and Worry gene would have been at loggerheads with one another. The same conflict would often manifest itself in the business environment when Winner wanted to reach for the stars. He was desperate to emulate Richard Branson, James Dyson and Steve Jobs and achieve great things. But Worry was always dithering and procrastinating about the best way to get there. He was always the blocker.

Mental Note

Look back in your life for any evidence that you might have inherited one or two ‘tricky’ genes. Your parents are a good place to start. Although these genes should never be a limiting factor, make sure you remain mindful of their ‘needs’. They may well be in conflict with one another and this can lead to problems in the professional arena. There is no doubt that different working environments require different genetic make-ups, so the better you understand the latter, the more likely it is that you will find a former that matches.

By Mark Simmons, Logistics & Planning at We Are Vision.

You can order Mark's book, Breakdown and Repair, on Amazon. You can also follow him on Instagram.