There are two kinds of politicians in Britain today. The ones people don’t like. And the ones people don’t know.

That’s the verdict of a 6000-person study we conducted using our Fame, Feeling and Fluency methodology – the method we use to establish brand strength and predict growth.

In our model, the 3 Fs represent the most powerful mental shortcuts people use when they choose brands.

Fame is awareness – how easily does this brand come to mind in a decision context? It relates most strongly to current market strength.

Feeling is the affect heuristic – does this brand make me feel good? When a brand has higher or lower feeling than would be expected given its size, it’s a good indicator of potential growth or decline.

And Fluency is how fast and easy a brand is to recognise and process – how distinctive it is. Fluency relates to the ability a brand has to charge a price premium.

The 3 Fs taken together provide a Star-Rating for brands – an indicator of their size and dominance in the market.

So what happens when we apply the 3 Fs to politicians, leaving their policies aside and treating them as brands? We’ve done it before – in January 2016 we identified Donald Trump as the frontrunner in the US presidential race before a single primary vote had been cast.

It’s a useful exercise because it identifies some of the deeper dynamics at work in the political scene.

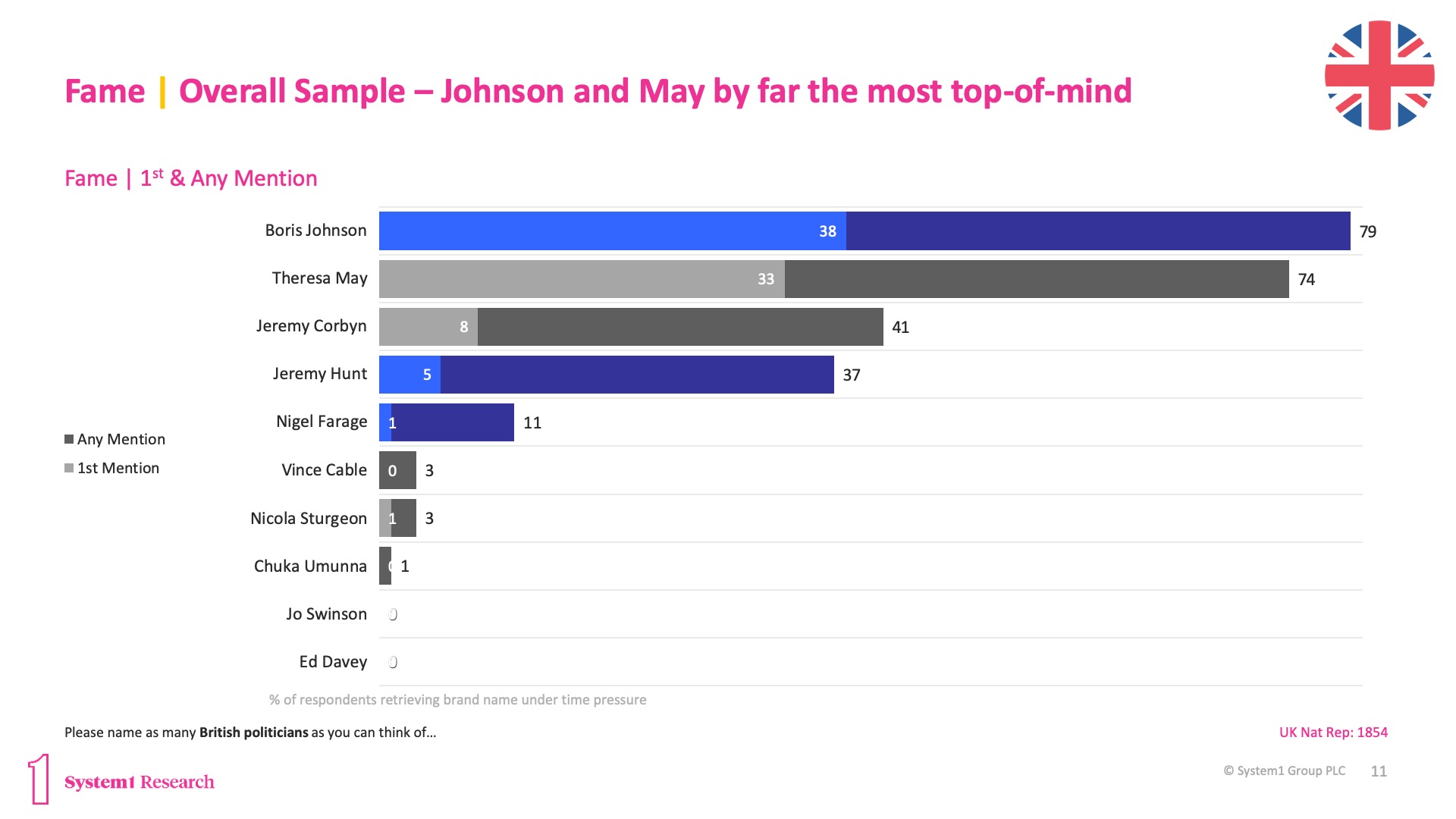

Fame breaks out of the media bubble – in which relatively minor figures can assume outsize prominence – to identify the politicians people actually notice.

Which is bad news for media darlings like Jacob Rees-Mogg, but it also affects some much larger names. The truth is, most British people find it hard going to name more than two politicians, and those two tend to be Boris Johnson and Theresa May (the incoming and outgoing PM). Two Jeremies – Labour leader Corbyn and failed Tory leadership candidate Hunt – come well behind.

But the real shocker here is the performance of Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage – inescapable in the media, but far from top-of-mind for the public. Only 11% of them name him without prompting. When prompted, he has high recognition, but he’s more of a sideshow than his media profile suggests.

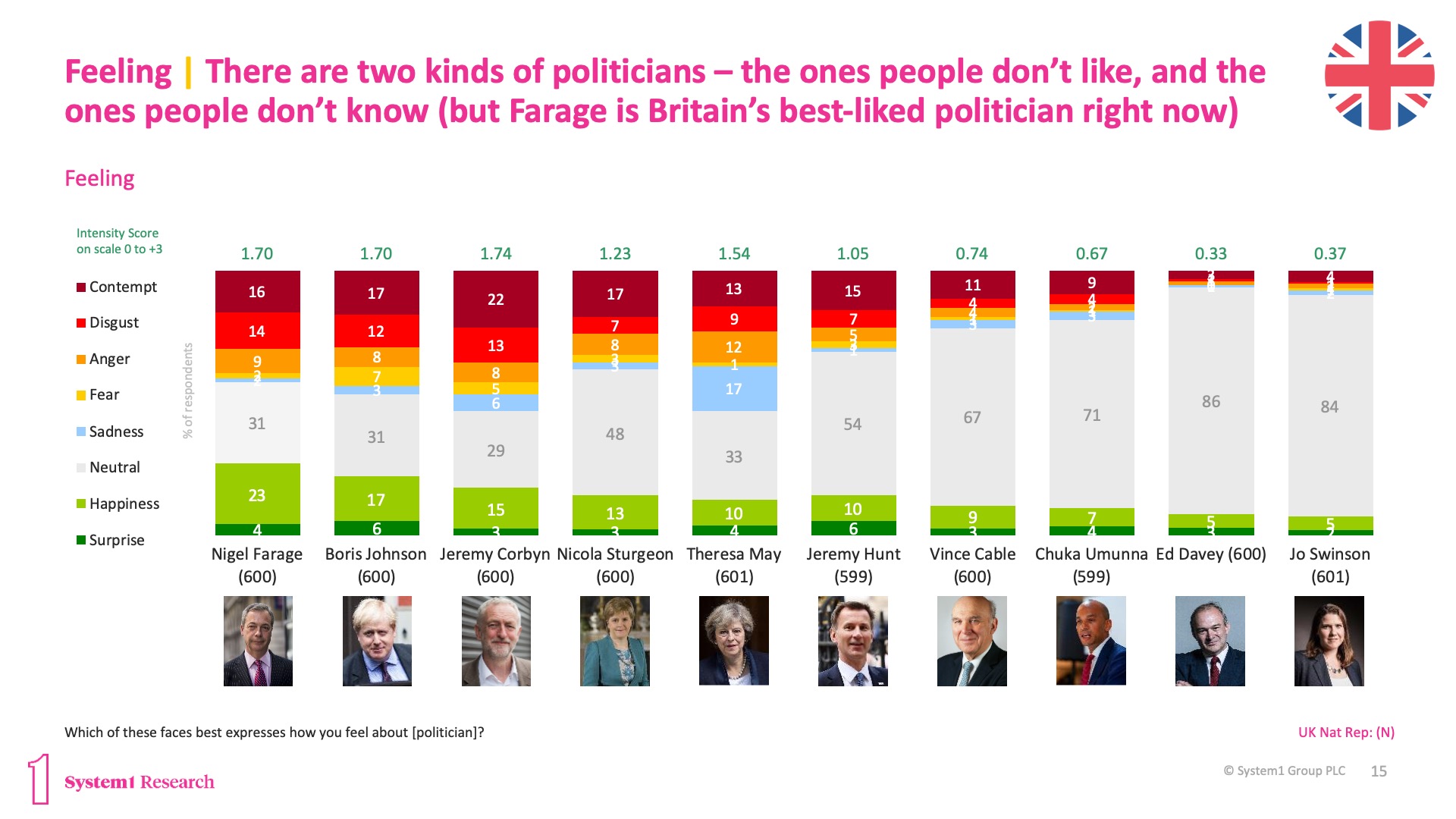

Feeling breaks down the politicians with the biggest reserves of goodwill – and those who the public strongly dislike. Satisfaction can shift up and down – strong negative emotion is tougher to move.

Which partly explains our current polarisation – there is a lot of negative emotion about, and nobody even begins to cross the political divide. This is a change from the last times we ran this study, when Boris Johnson was the closest we had to a popular figure across political lines. Now the number of people who say they feel happy about Johnson has plunged from over 30% down to 17%.

The silver lining for Johnson is that most of his current and former rivals perform equally poorly. Jeremy Corbyn has 15% Happiness and over 50% negative emotion (the most negativity of any politician) – and no other Labour figure is even on the public’s radar. Hunt and May’s scores are similarly atrocious.

In fact the best-liked politician in Britain right now is Nigel Farage – though with 23% Happiness against 46% negative emotion, “best-liked” is a stretch. But here’s where things get tricky for Boris.

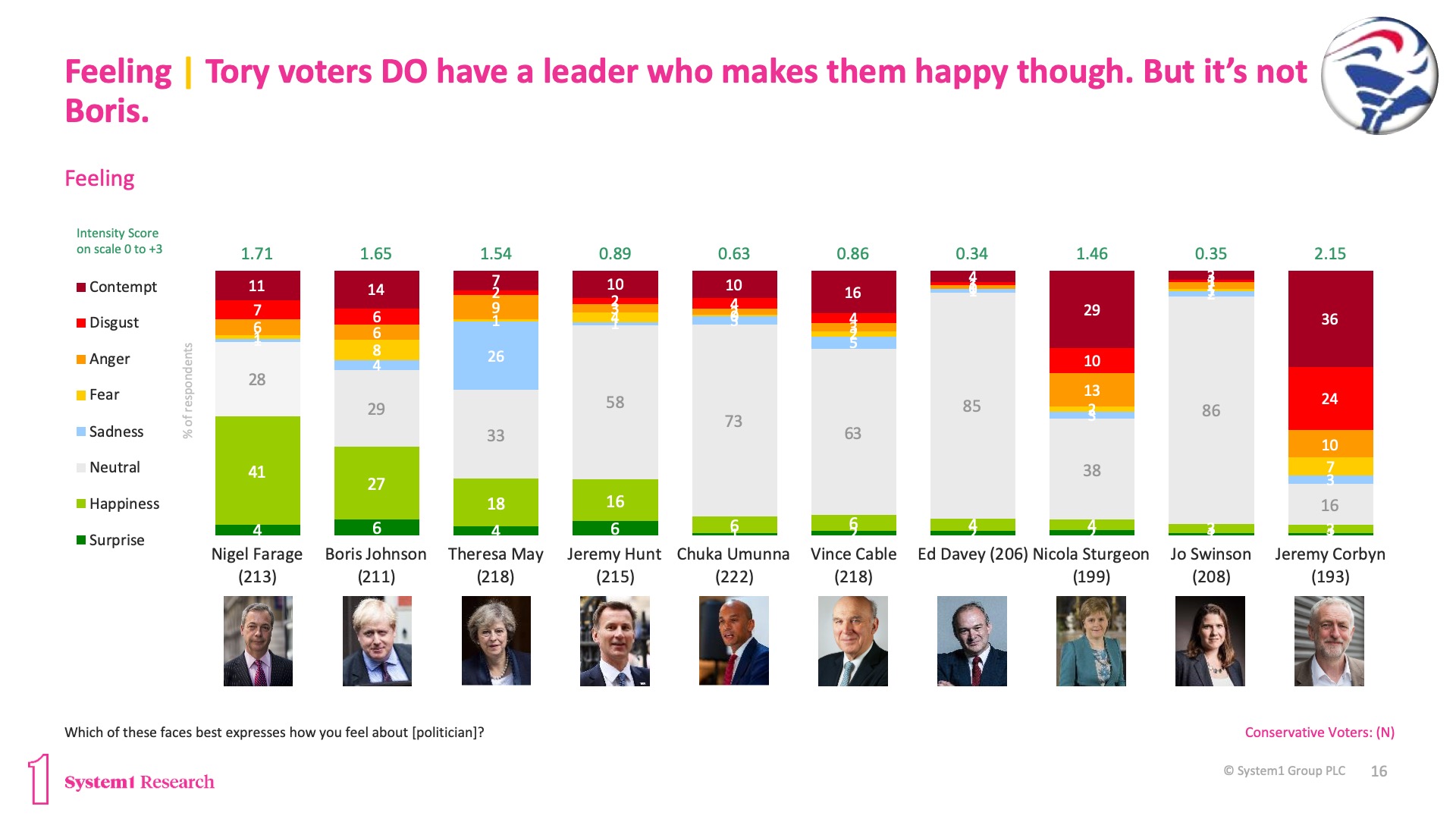

Because Farage’s emotional pull isn’t limited to his loyal Brexit party fans. When we looked specifically at Conservative voters, we found their level of Happiness with Farage was 41% – strong for a politician and well above the 27% Happiness those same Tories feel about their new leader!

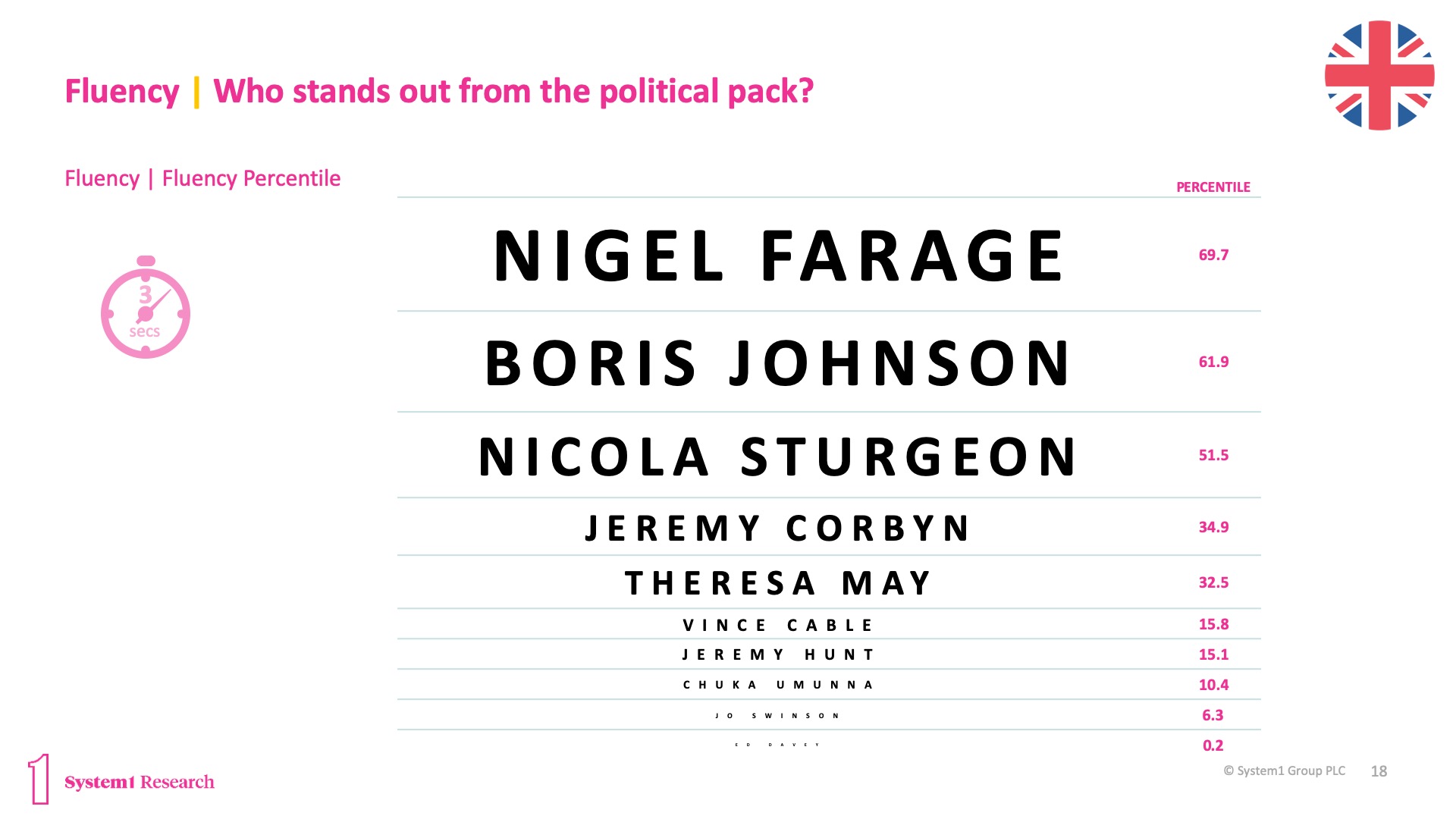

Fluency identifies the truly distinctive politicians – whether through their policies, their personality, or both. While there’s no direct political equivalent of being able to charge higher prices, we’d hypothesise Fluency represents something even more valuable to the modern politician – imperviousness. The politicians with higher Fluency (like Trump) tend to be those who can shrug off scandals, because there’s no easy replacement for them.

Here, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage both score extremely strongly – just as Donald Trump did in the US. High Fluency, we’d theorise, makes a politician hard to effectively oppose – criticisms which would land with a less distinctive opponent are less likely to land a blow.

The FFF method helps us understand the underlying dynamics in politics, just as it does in a market. With no politician scoring well on Feeling, Boris Johnson’s big leads over Jeremy Corbyn on Fame and Fluency should give him a decisive advantage should he go for an early election. But there’s a wild card in the form of Farage.

Looking at our brand database for an equivalent of Nigel Farage’s results among Tory voters, we found similar patterns in indulgent treats – like cake brands. They aren’t top of mind as a choice, and there’s an element of dislike (people know cakes are bad for them) – but they’re also a highly distinctive option which creates a lot of positive feeling. While British voters as a whole are no fans of Farage, for Tories he’s an exciting temptation. Britain’s new PM’s fate may rest on whether his voters can resist it.

This piece first appeared on the System1 website here