On 6th November 2012 Barack Obama was re-elected into the White House. Many have speculated on how he beat Mitt Romney and one of the key factors may have been how he made incredibly good use of insights from behavioural economics and psychology in his campaign. Obama recruited a consortium of behavioural scientists for the 2008 election, asking them to pass on relevant research findings and ideas on creating effective behavioural change to his campaign team. The 2012 campaign built on that, drawing heavily on tools from social science, not just in areas like how to get people to vote, but in their research strategies too.[1] Here are some of the clever interventions they used.

Mapping the behavioural journey of potential voters

One thing the campaign team focused on was spending time mapping voters' ‘behavioural journey’ – to determine what prompts and triggers during the campaign period might steer a potential voter to finally casting their vote and what potential barriers might exist or arise to deter them.

One crucial area in the mapping was what potential voters watched on TV and listened to on the radio. Political advertising in the US is a large part of the campaign so this was a crucial element. Obama’s team looked at what their target voters did, what they watched and what they listened to in order to tailor the advertising campaign most effectively. This revealed some big surprises. Jim Messina, Campaign Manager for Obama commented that:

“Every campaign buys the nightly news and 60 Minutes but we found out our target voters weren’t there. They were watching shows you and I had never heard of.”[2]

Through this deeper behavioural understanding they were able to fit the Obama media campaign to each state:

“One size does not fit all: In each swing state, the Obama campaign utilized a different media mix, varying the amount of money spent on broadcast television, cable television, radio, digital, mobile, and social media advertising, based on the media data about the state and the target voters they were attempting to reach.”[3]

Making a plan to vote

The campaign team also looked at people’s behavioural journey to casting a vote. We might have every intention of voting, but we often overestimate our ability to vote on the day. We're subconsciously influenced by a number of different behavioural economic concepts such as procrastination, time inconsistency and optimism bias, and they combine to make us lazy - we put off making a plan, or find when the day comes, we haven’t allowed enough time, or haven’t investigated where and when we have to go to cast our vote. In this day and age it is even easier not to make concrete plans; the ease of instant communication via mobile phones and the internet allows us to make and change our plans so quickly and this reduces the level of commitment we might feel to planning itself.

The campaign team were guided by research such as that of two behavioural scientists based at the University of Notre Dame and the Harvard Kennedy School - David Nickerson and Todd Rogers – who had looked at how asking eligible voters to make a plan to vote affected turnout in 2008. They randomly assigned 287,000 people eligible to vote for the 2008 Presidential election in Pennsylvania into one of three groups – a control group who were not contacted at all, a standard group who were telephoned using the standard ‘Get out the vote’ (GOTV) script and finally a ‘make-a-plan’ group who were also asked after the GOTV script, what time they would vote, what they were doing beforehand, and where they were coming from to vote. After the election examination of the turnout data showed that asking people about their plans to vote raised turnout rates by 9% among households with only one eligible voter, but had no noticeable impact on households with multiple voters. They reasoned that it is much easier for a single voter to make a plan to vote as they will not have to factor in the plans of other people. Households with multiple voters may need to discuss any plans to vote and make arrangements together.[4] This shows how understanding context in detail is critical.

Making a plan can help us achieve a goal or task and there are three different mechanisms from the behavioural sciences which are key in facilitating behavioural change:

- Chunking: we think through the logistical aspects of voting and chunk or break down the task into different parts – making sure you have your ID, which bus will you catch, leaving work a bit earlier, getting someone else to pick the kids up from school etc;

- Commitment bias: by setting ourselves a defined task or goal we might feel more committed to achieving it and think a bit harder about how to overcome possible setbacks which arise on the day, perhaps an over-running meeting at work; and

- Memory triggers: the plan creates the triggers in our memory which help us to carry out the right parts of the task at the right time eg if part of the plan to vote is to arrange for a neighbour to watch the kids while you go down the road to vote, your neighbour arriving on your doorstep will prompt and trigger your memory of the next step in your plan.

With these three mechanisms in mind, campaigners got people thinking about their voting plan using a range of different communication strategies.

- First, on telephone calls to voters, they asked people if they had made a plan to vote and if not to make one, asking them to specify a time when they would vote, for example.

- Second, emails were sent to voters which included the motivating question

“People do things when they make plans to do them; what’s your plan?”

Dr Susan Fiske, a researcher at Princeton University and a member of Obama’s consortium of behavioural scientists says she received a mass email from the Obama campaign saying just that.

- And third, billboard campaigns helped to get voters thinking about three key aspects of planning to vote ‘When, where and how’, similar to Nickerson and Rogers’ research (see images below).

Commit to vote

Commitment bias was also utilised by asking people if they would sign a ‘Commit to Vote’ card. This was an informal card with the president’s picture on it (see images below). There is substantial research showing that making a pledge in public and the action of signing to agree to do something that makes us feel more committed to doing it. Further, images are more salient and therefore usually more powerful than words, priming us to carry out certain behaviours, so the photograph of Obama may have had an additional impact on voting.

I am a voter!

The campaign also recognised that people are more likely to vote if they are reminded of their identity as a voter. This could be due to a number of reasons:

- Priming or making an identity more salient: We have ‘multiple selves’ and identities and each self can be more salient at different times. For example, you are reminded of your identity as a father at a school parents’ evening. Similarly, you remember you have an identity as a voter when you are reminded that you have voted in the past. So the key was to make this identity salient.

- Social norm: Voting is also something we know we should do, what behavioural scientists call an ‘injunctive social norm’. We generally want to see ourselves as competent, moral and approved of socially.

- Cognitive dissonance: We also want to avoid cognitive dissonance, where we experience mental discomfort due to doing something (or not doing something) so as to act in a way which is contrary to our beliefs or opinions. Not voting goes against our belief that voting is something we should do and have done in the past so being reminded of our past identity as a voter can be subtle prompt. “People want to be congruent with what they have committed to in the past, especially if that commitment is public.” says Robert Cialdini who is a member of Obama's consortium of behavioural scientists.

So when the Obama campaign team began knocking on doors, they immediately identified people as voters eg “Mr Johnson, we know you have voted in the past” reminding people that they need to affirm that identity again and using the past as an anchor or a reference point from which to guide future behaviour.

There is continuing research into the impact of small language changes. A recent study by researchers at Stanford and Harvard University found that a simple linguistic cue via a change in wording for a request to vote had a very powerful impact on reminding people of their identity as voters. They conducted two randomised trials during two state-wide elections in the US. One group was asked a question with noun-based wording: “How important is it to you to be a voter in the upcoming election?” Another group were asked the same question but with verb-based wording: “How important is it to you to vote in the upcoming election?” Research has found that noun-based wording makes people think of the noun and all its essential qualities and attributes. For example, saying “I am a painter” is more definitive than saying “I paint a lot”. And the same goes for voting: Saying “I am a voter” defines more about who you are than saying “I vote”. The results demonstrated that the noun-based question lead to a higher turnout rate than the turnout rate amongst individuals who had been asked the verb-based question in both elections: 96% vs 82% in the 2008 California state election and 89% vs 79% in the 2009 New Jersey gubernatorial election.[5]

Did my Neighbour vote?

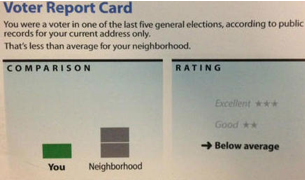

A range of political organisations during the election also mailed out Voter Report Cards showing someone their voting activity over the last five years and comparing it with the neighbourhood average turnout rate. This is a simple way of using social pressure and neighbourhood norms to encourage and nudge people into voting. Similar trials to reduce household energy use – where households are told how their energy use compares to the neighbourhood average - have shown that these kinds of social comparisons are effective in changing behaviour.

Countering myths, lies and slander

The campaign team used behavioural sciences more broadly than simply getting people to vote. They applied it to other areas such as their communications strategies. In a typical election campaign there are always myths and rumours (often tantamount to slander) flying around and parties and candidates have to do their utmost to counter these. So the campaign team addressed the issue of how to counter rumours, myths and outright lies most effectively. Research conducted by them into countering myths and rumours has illustrated a number of crucial points.

One is that the more we hear a false rumour or myth the more likely we are to believe it to be true, it's known as repetition bias. Our minds make use of heuristics (short-cuts or rules of thumb) and one of our rules of thumb is that things we hear often must be or at least tend to be true.

In addition, in the long term, we tend to remember stuff we have heard or read not in full but only as a kind of truncated word association in which the most vivid elements stick with us and the qualifying expressions get a tad blurry: eg where the initial phrase we might hear or read is actually 'Roberto is not in the Mafia' after a while we'll recall only ‘Roberto’ and ‘Mafia’ inextricably and (perhaps) erroneously linking the two. We seem to forget the ‘not’ or the negative part of the statement over time.[6] Our long term memories are often poor - especially for subjects and facts on the periphery of our interest, which presumably the Mafia is for most readers…! On this basis it's probably wisest to give no air time at all to denials as it's likely this will only serve to strengthen the falsehood in the minds of listeners.

Research on countering health and disease myths illustrated this clearly. In one study on myths about the flu vaccine, participants were asked to read through one of two versions of a flyer published by the US Center for Disease Control: a ‘Myths and Facts’ version which listed six myths about the flu vaccine and countered each one with a fact, and a second version of the flyer stating the facts alone. After reading the flyers, participants were tested on their recall of the version they had read. Immediately after reading the Myths and Facts flyer, participants had a good memory and only identified 4% of the myths as true, and only 3% of the facts as false. However, only thirty minutes later, they were retested and in that short space of time, participants’ memory had worsened to the extent that they now identified 15% of the myths as true and were less inclined to have the vaccine than the control group who had read no flyer at all! Three days later accurate recall of myths v facts had deteriorated still further.[7]

This research shows it is more effective to counter a myth by simply stating the true facts and leaving the myths well out of it. Obama’s campaign team realised that denying rumours for example, that Obama was a Muslim, by crying “Obama is not a Muslim!” would have little effect. So instead they repeated (and repeated…) that ‘Obama is Christian’ – strengthening people’s association between Obama and Christianity rather than Islam.

This is a BE masterclass in how combining deeper behavioural understanding with a range of cognitive biases can nudge and steer behaviour in many different ways.

Read more from Crawford Hollingworth.

[1] New York Times “Academic ‘dream team’ helped Obama’s effort” 12 November 2012

[2] FT “How the White House was won“, 12 November 2012

[3] Business Insider: “Obama's Media Planner Tells Us The 5 Most Important Ad Tactics From The Presidential Campaign” 12 November 2012

[4] Nickerson, D., Rogers, T., “Do You Have a Voting Plan? Implementation Intentions, Voter Turnout, and Organic Plan Making”, Psychological Science 21(2) 194–199, 2010

[5] Bryan, C.J., Walton, G.M., Rogers, T., Dweck, C.S., “Motivating voter turnout by invoking the self” June 2011, PNAS 10.1073

[6] Mayo, R., Schul, Y., Burnstein, E. “’I am not guilt’ vs ‘I am innocent’: Successful negation may depend on the schema used for its encoding. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40 (2004) 433-449

[7] Skurnik, I., Yoon, C., Schwarz, N. “Education about flu can reduce intentions to get a vaccination.” (2007)