Fame, feeling and fluency drive political predictions, says Tom Ewing, Senior Director, BrainJuicer Labs.

Back in January, America’s political pundits were close to united, and had been for some time. In the imminent primaries for the Republican presidential nominee, Donald Trump had little chance. Yes, he was ahead in the polls. But outsider candidates had risen and fallen before, and Trump faced what seemed to be a strong field. Jeb Bush had the war chest. Marco Rubio fit the profile. Ted Cruz, it appeared, had the hardcore conservative vote locked up.

And when Trump came in a narrow second place to Cruz in Iowa, the first Republican Caucus of the year, those opinions seemed vindicated. On Predictwise – an amalgam of polls, betting markets, and bookmakers’ odds – Trump plunged to a 25% chance of landing the nomination.

Clearly, the pundits were wrong. And while the US polls were right for Trump, their UK equivalents had been disastrously off predicting the 2015 general election, and most of them called the Brexit vote wrong too. What were pollsters and commentators missing?

At its root, polling is all about claimed future behaviour. As commercial researchers, we know this is a poor guide to actual outcomes. So we feel the answer to the polling dilemma lies in behavioural science, with the mental System 1 shortcuts consumers use when they make decisions about brands and purchase choices. If you can measure those, you have a good proxy for likely future behaviour, without having to ask about it. These core heuristics can be used to predict market share and brand growth – maybe they could also predict political outcomes?

So we were watching the Iowa results too – with the data tables from our first wave of “System 1 Politics” data (check out our live updates), designed to measure these heuristics, hot off the virtual presses. And as soon as we looked at our data we realised two things.

First, that the election was going to be Donald Trump v Hillary Clinton: the other Republicans had no chance, and nor did Bernie Sanders, though he was closer. And second, that it was going to be a close race.

This piece isn’t about us being right or not, though. It’s about the heuristics – the factors that influence System 1 decisions, be they in branding or politics. Fame, Feeling and Fluency.

Fame is all about familiarity – does a candidate come easily to mind? Feeling is all about emotion – does a candidate make people feel positive? And Fluency is all about recognition – is a candidate distinctive and easy to mentally process, and do they command distinctive assets which they are easily associated with?

Or to put it another way. You ask someone to name a football team, and they say Manchester United. That’s Fame. You ask how they feel about Manchester United, and they give you a big smile. That’s Feeling. You show them a picture of David Beckham, and they say Man U (not England or Real Madrid) – that’s Fluency.

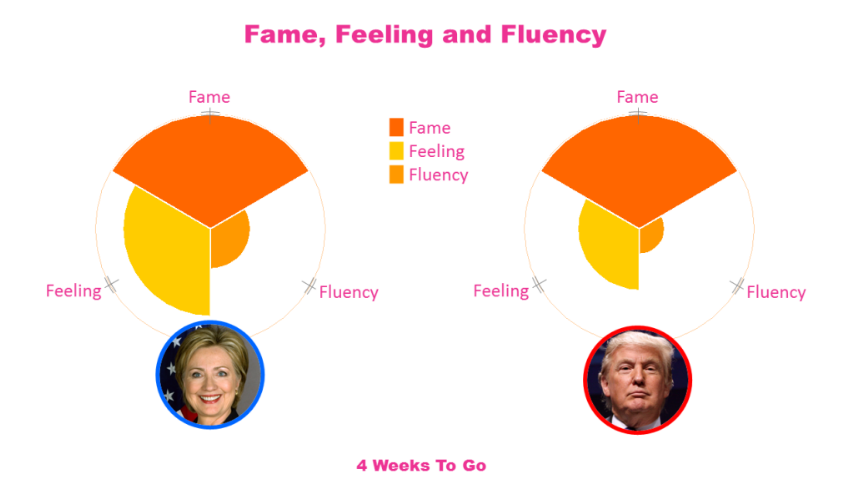

Each of Fame, Feeling and Fluency have played a different role in the US election, and the story of how it’s unfolded has been down to how Clinton and Trump have built (or lost) each factor.

FAME: TRUMP’S PATH TO PROMINENCE

Why was it obvious Donald Trump was going to be the Republican candidate, even though commentators assured us it was impossible? Because he smashed his opponents on the 3Fs, and in particular Fame. Trump himself has described this as the key to his strategy – he credits the massive amount of free media he got for driving him through the primaries. And, of course, he was enormously well-known already. Does that mean that if, say, Kanye West were to run next time round, he’d win? Not necessarily: Fame is all about familiarity in context – Trump’s existing fame helped, but it was the media covering him as a presidential candidate that made him famous in that context. His opponents never had that initial recognition factor, and Trump’s outrageous speeches drove their media presence down.

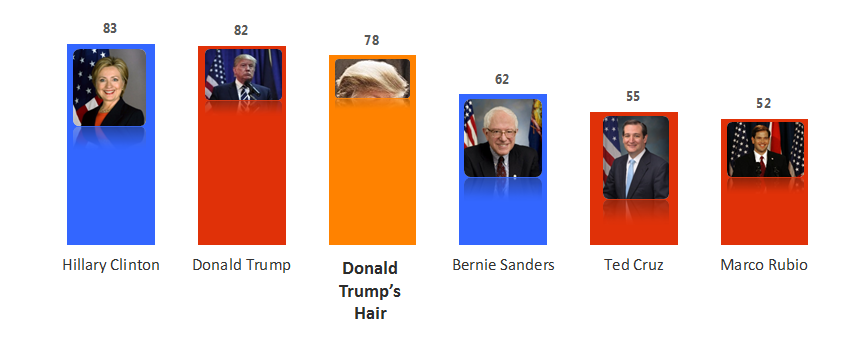

How far was he ahead? Under time pressure, not one of the remaining Republicans was as familiar to our respondents as a picture of Donald Trump’s Hair.

In the general election, Fame has been less of a factor. Not because the spotlight has faded, but because he’s running against the only Democratic politician with as much instant recognition and existing fame as he has. Hillary Clinton matches him on Fame, which means the difference between the two of them pivots on the other two Fs.

FEELING: CLINTON’S REAL FOUNDATION

Being well-known doesn’t get you to the White House. You need to be well-liked. And if you aren’t, you’d better hope folks like your opponent even less. This is the position Hillary Clinton has found herself in. As is now well-known, Clinton and Trump are the two most disliked nominees since election polling began.

And the dislike is visceral. In Britain, when we look at the emotions people feel about politicians, the dominant negative emotion tends to be Contempt – eye-rolling disdain for their conniving ways. In America this election year, the dominant negative has been Disgust – a primal, get-it-away-from-me feeling of revulsion.

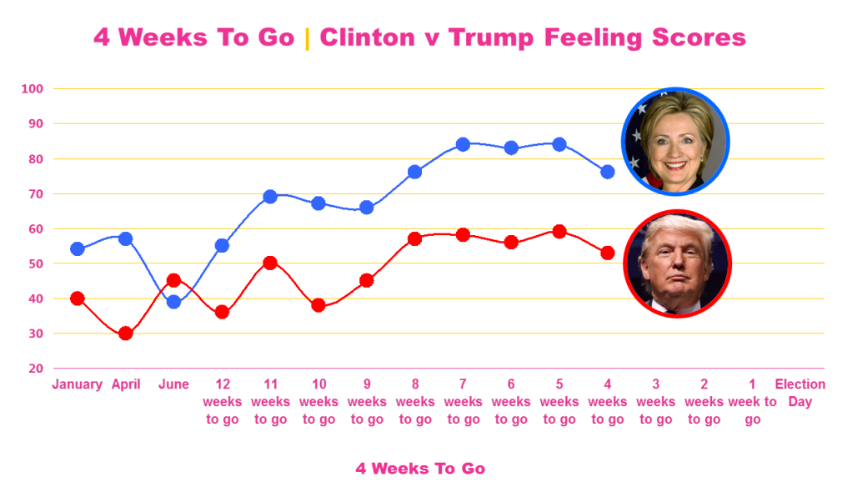

But across the dozen waves of data we’ve looked at, only once has Hillary Clinton fallen behind Donald Trump on Feeling (in June, just after the FBI censured her over her email server). Since August, she’s maintained a solid lead over him, and has even grown it. She’s still not popular – she’s never got above 41% of people saying they feel Happy with her. But Trump has never topped 30%. It might not be nice being the lesser of two evils – but if the data consistently shows people think you are the lesser, you still have the edge. Clinton’s Feeling lead has been her main advantage against Trump.

Why do people like each candidate? Despite waves of news stories, scandals, and counter-attacks, response has been remarkably consistent. Back in January, people liked Clinton’s experience and disliked her dishonesty, and people liked Trump’s plain-speaking and disliked his rudeness and bigotry. Over the entire year, even if Feeling has changed, the reasons haven’t. The lesson for brands? Changing perceptions of strengths and weaknesses is a hell of an effort – better to work with what people already believe.

FLUENCY: THE TRUMP CARD?

So if Clinton has continually led on Feeling, why has the race even been close? The answer is Fluency: how distinctive each candidate seems, and the mental associations and assets they have built up. From the beginning, it was Trump’s pet issues and policies – particularly immigration – that dominated coverage of the election. And the distinctive assets associated with Clinton – particularly her emails – were thoroughly negative.

But even looking at the issues doesn’t capture how well Trump was winning on Fluency. In a line-up of establishment Republicans, Trump effortlessly stood out. Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, trailed on Fluency to her left-wing challenger Sanders. Trump was simply far more distinctive than his rivals. An illustration of how completely Trump owned the conversation is that when we tested associations with candidate slogans, people linked every single one with Trump. Even Bernie Sanders’ “A Political Revolution Is Coming” was credited to The Donald. And the most Fluent slogan of all? “Make America Great Again”.

So back in January the election looked close. Level on Fame, Clinton ahead on Feeling, Trump winning Fluency. Put it all together – in the model we use for predicting brand growth – and we predicted Clinton would build a narrow advantage as the campaign proceeded.

But as the election enters its final stretch, it’s continued to surprise. And not in the way you might have expected.

THE FINAL STRETCH

For brands, Feeling can change quite rapidly – think VW when the emissions scandal hit, for instance. But Fluency tends to stay the same – brands work carefully to cultivate and control their assets. So we imagined this political race would operate in the same way.

We were wrong. Weekly data dips over the last two months have shown a race where Clinton’s lead on Feeling has been strong and steady. But to our surprise, people have felt better about both candidates, and the succession of shock events and scandals (like Clinton’s stumble or Trump’s Twitter meltdowns) hasn’t shifted these underlying dynamics. It’s early days – and our latest wave of data came before fresh accusations of harassment - but even Trump’s on-tape gloating over sexual assault hasn’t yet had much impact on Feeling.

How can this be, especially when previous incidents, like the FBI censure, did shift Feeling? As people’s opinion hardens and settles, what psychologists call ‘motivated reasoning’ sets in, where new information is fitted into an existing narrative and worldview. So both candidates have seen an overall rise in Feeling in the final weeks, which the drama has done little to shift.

Fluency, on the other hand, has moved a lot. Donald Trump’s advantage lasted through the Primaries and into the early stages of the General Election, but has since collapsed. He is seen as no more distinctive than Hillary Clinton. Again, the imminence of the election has a lot to do with this. The more the election turns into a familiar Democrats v Republicans polarised race – albeit a lot more incident-packed and intense - the less distinctive the Republican candidate becomes.

The first debate was an opportunity to change that – to build Fluency and push his distinctive assets, like the Wall. But he hardly mentioned immigration, and gave Clinton the chance to promote her strong associations – like her political experience. The result? A jump in Fluency for Clinton post-debate: for the first time, she led on it.

With less than four weeks to go, the Fame-Feeling-Fluency analysis shows a race that isn’t completely decided in Clinton’s favour, but in which she holds a solid advantage. She leads strongly on Feeling and narrowly on Fluency. Might Trump’s continual attacks dent that lead? It’s possible – the very latest data, collected after the second debate, shows a dip in Feeling for Clinton. But it also shows a similar dip for Trump – people growing weary of the entire wretched election. That does him no good.

The question is – does this have anything to do with reality? Measuring proxies for baseline System 1 heuristics instead of asking voting intention is an unconventional way of looking at an election. But those heuristics govern how we live our lives. For brands, the 3Fs are validated against real world behaviour – share, share gain, and pricing. Are politics really so different? The measures have moved in line with the polls – if anything, they’ve anticipated polling movements by a week or so. In which case (and depending on the impact of new shocks and events) we’d expect Clinton’s current strong lead to narrow slightly before Election Day.

Where this kind of work feels particularly valuable, though, isn’t in tracking the race close to election day, but in exposing the dynamics and probable outcomes months or even years ahead. People’s intuitive judgements, once made, are tough to shift, and questions about emotion, distinctiveness and familiarity reach that intuitive layer better than questions about the more rational world of voting intention. They meant that we could identify, before a single vote had been cast, the candidates, their strengths and weaknesses, and the dominant issues.

And we could also predict the likely outcome: the first female President, but only after the most gruelling political race of our lifetimes.