There have been countless behavioural science based initiatives intended to nudge healthier eating. But which ones actually work, leading to a sustained behaviour change? And of those, which are most effective? What concepts, tools and styles of intervention are best at getting us to eat healthy foods, or less of the unhealthy foods...?

To tackle this question, two French researchers, Romain Cadario and Pierre Chandon, have endeavoured to make sense of all the research, collating together all the behavioural science-inspired interventions which took place in real-world environments - cafeterias, restaurants and grocery stores - and excluding any online or lab-based experiments. They then analysed the results altogether (known as a meta-analysis), excluding any studies reporting only intention-based findings, focusing instead on those that could report an objective measure of behaviour such as food weight or energy consumed.

In total, after a careful search, they have narrowed down the existing research to 88 studies that have been published in 82 articles. This included studies on both children and adults. A large proportion of the studies were conducted in the US, with others from Belgium, Canada, France, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Netherlands and the UK. They then set about categorising the varied interventions into seven different types, across three areas.

In this article, we’ve brought these seven areas to life below, extracting the main features, examples of application and summing up what works - as well as what does not:

1) Knowledge-based nudges

This area tries to change behaviour by sharing information and increasing knowledge and awareness.

Descriptive nutritional labelling:

This includes initiatives like providing calorie or nutritional information on food packaging and on menus, to encourage consumers to select lower-calorie options. It’s becoming increasingly popular and can be seen in many of the well-known international food chains, such as in Starbucks (shown here).

In fact, Bryan Bollinger and his colleagues analysed Starbucks sales data to evaluate the impact of the NYC law mandating nutritional labelling, implemented mid-2008.

Analysing data before and after the change, they found that though there was a decrease in calorie consumption after the posting of calorie information, the reduction was small and was almost entirely due to a change in food choices, with almost no change in drink consumption (its core product type).

Some argue that the impact could be improved with better health education about labelling, but often even the most informed customers pay little attention to this type of information.

Evaluative nutritional labelling:

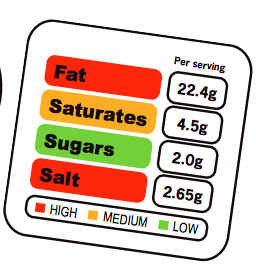

Whilst also providing nutritional information, this approach tries to make it easier for consumers to understand and interpret the information, by utilising simple wording and visual heuristics - such as colour coding or types of scoring to highlight recommended items.

Typically, green indicates healthier options and red, unhealthy options. Another approach is to place special symbols such as smileys and heart icons, indicative of healthier food groups, on the packaging or menus.

Impacts seem to vary - whilst some trials have had a small to moderate impact, others have had none.

For example, the ‘traffic light system’ has been applied in many contexts from supermarkets, to school cafeterias, to food halls in sporting centres. One example of this was implemented in a US hospital cafeteria in 2012. Foods were rated on three positive and two negative criteria; the positive criteria were having the main ingredient be a 1) fruit or vegetable, 2) whole grain, or 3) lean protein/ low fat dairy, and the two negative criteria were saturated fat and calorie content.

Those with more positive criteria were green, more negative criteria were red, and equal quantities were yellow.

Douglas Levy and his colleagues then compared changes in consumer choices of green, yellow and red foods before and after, finding that the initiative had a small impact on food choices. There was a modest decline in purchases of food groups labelled red (by roughly 11%) and a small increase in purchases of those labelled green (6.6%).

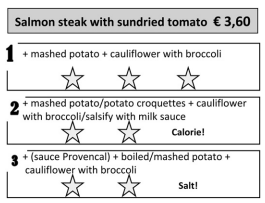

Conversely, another trial in a university cafeteria in Belgium examined the impact of a 3-star recommendation system - similar to Michelin stars - to draw attention to healthier items and caution against unhealthier items (see example).

Unhealthy features - such as high saturated fat content, salt or sugar content or calorie content - were also highlighted in red font and marked with an exclamation.

However, in this case, meal choices in canteens and nutrient intakes did not improve after the intervention.

Salience enhancements:

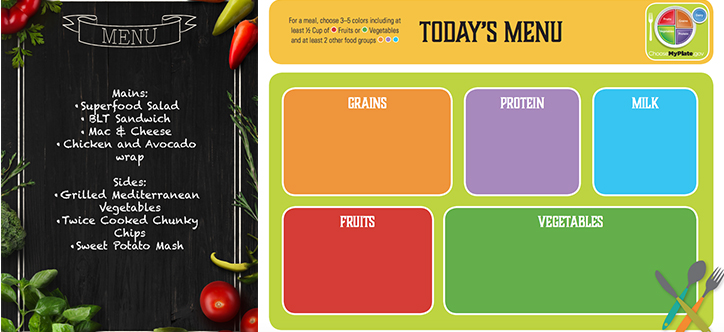

By placing healthy options in more visible positions such as on shelves, at the top of menus, near the checkout register, or in transparent containers, they can be made to stand out to customers. Alternatively, placing unhealthy options further down the menu, or at the very top/bottom shelf, reduces the visibility to the consumer by moving it away from eye-level.

Again, the evidence is mixed. Some trials have found a modest impact, while other trials have found no impact at all. Eran Dayan and Maya Bar-Hillel tested the placement of choices on the food menu of a cafe in Tel Aviv.

They found that moving an item from the middle of the menu to either the very top, or very bottom, increased its popularity among customers by roughly 20%. So if healthier items were placed at the top or bottom positions on menus, consumers may be more likely to select these options.

However, in another trial run in food stores in 2 districts of Marseille, there was little impact from a multi-pronged campaign to encourage the purchase of inexpensive but highly nutritional food items. The campaign - named ‘Manger Top’ meaning Eat Great - promoted foods such as pulses, canned fish, eggs and fruit and veg using shelf labels, shelf placement and in-store posters and leaflets and taste-testing

2) Affective nudges

This area of nudges play on our feelings about food and try to generate some sort of emotional response.

Sensory cues

This type of intervention tries to increase the System 1, sensory appeal of healthy options, rather than informing consumers about their nutritional quality - a more ‘System 2’ approach.

For example, restaurants might use emotional, vivid, affective descriptions or attractive displays, photos or containers.

Two elementary schools in western New York redesigned their cafeterias in the summer of 2011, using sensory cues such as a more attractive menu (as shown), fruit displayed in attractive bowls, and vegetables labelled with descriptive names (e.g. “Celery Swords” and “Krazy Kale”).

Andrew Hanks and his colleagues found that this lead to an increase in the consumption of fruit and veg - an 18% increase in fruit consumption and 25% increase in veg consumption.

Children were also more likely to consume an entire portion of fruit or veg. They also estimated a modest but significant increase in those actually consuming the selected fruit and vegetables.

Healthy eating cues

These provide a direct message to the individual to eat better.

The messages can be both oral and written and either aim to steer people to choose a healthier option (e.g. “Make a fresh choice!”), or to change their unhealthy choices (e.g. “Your meal doesn’t look like a balanced meal”). Whilst seeking to change people’s eating goals, from taste to health, these messages might also leverage what are known as injunctive social norms - an indication of what society approves of - as they do in the examples above.

The Cafeteria Power Plus Project, initiated in 2000 across 26 schools in the metropolitan area of Minnesota ran for 2 years.

It utilised healthy eating cues (“which vegetable would you like for lunch?”) along with other sensory cues (posters in the cafeteria of life-size fruit and vegetable characters called “The High 5 Flyers”!) and healthy eating challenges (a competition to eat 3 fruit or vegetables per day at lunch for a week, with prizes for those who succeeded) to encourage young children in schools to eat more healthily.

By the end, children’s eating behaviours had changed as a result of the program.

3) Action/behaviour-based nudges

These types of nudges focus on directly steering our choices and behaviour, often by default in what we are offered.

Convenience enhancements:

Some behavioural interventions can change people’s behaviour without necessarily influencing what they know or how they feel.

What are known as ‘convenience enhancements’ do this by making it easier to select or consume healthier options, such as fruit and vegetables in ‘grab and go’ cafeteria lines, convenient utensils or the pre-sliced, pre-portioned food options currently available at most major supermarket stores.

At first glance, this type feels quite similar to the salience enhancements above.

However, convenience enhancements are more about making food and drink choices more physically available - easier to grab, whereas salience enhancements are more about making things more visible to the eye for example on a menu but also on a shelf.

This intervention can also make it more cumbersome to select or consume unhealthy options such as putting unhealthy options later in the cafeteria line when trays are already full, or in the middle rows of food bars so they are more awkward to reach. Many studies have indicated that accessibility can affect what people choose.

For example, Paul Rozin and his colleagues found that positioning food on the salad bar in the front rows or in the less accessible middle rows affected what people chose. When unhealthy food was made less accessible, its selection was reduced by a range of 8-16%, which can have potentially substantial impacts on weight loss and habitual food choices.

Plate and portion size changes:

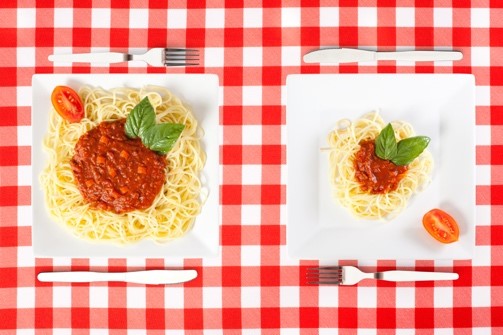

Leveraging behavioural insights on default options (our tendency to stick to the default option suggested to us), this intervention modifies the size of pre-plated portions of food and drink, often found in cafeterias and cafes. T

his might increase the amount of healthy food offered or, more commonly, reduce the amount of unhealthy food in a portion - such as smaller ice creams or portions of chips.

The effect of portion size on how much we consume is significant; when we are given more, we tend to eat more!

Nicole Diliberti and her colleagues studied this effect by varying the size of a pasta entree at a cafeteria-style restaurant in Pennsylvania on different days, from a standard portion (248g) to a large portion (377g). Those who purchased the larger portion did indeed eat more, increasing their energy intake of the entree by 43%. When asked about the appropriateness of the portion sizes, there was no difference in ratings between the consumers of the large portions and of the regular portions. Customers also reported no difference in how much they enjoyed the meal, rating it identically.

The only significant difference between the portions appeared to be that customers rated the larger portion as better value for money.

This finding not only suggests that large restaurant portions may be contributing to the obesity epidemic through overconsumption, but also that customers are not totally aware of portion sizes. Their results are consistent with other studies in this area and provides compelling evidence in favour of modifying portion sizes to discourage overconsumption of calories and unhealthy foods, as well as encouraging the consumption of healthier options.

In another study, college students in the US typically ate in the onsite cafeteria where they could purchase an 88g gram bag of french fries, containing around 24-28 fries. Over the course of 3 weeks the contents of the bag decreased by 15g per week meaning that by the end of the experiment, the bag was half the size with only 12-14 fries in! This amounted to a reduction of 150 calories and the majority of diners - 70% - did not notice the reduction in portion size.

Even when the portion was half its original size, some 51% of diners still chose only one bag compared to 87% at the start, and those who were now choosing two bags of fries rather than one were eating no more than they were at the start. The researchers calculated that portions could be reduced by 17–34% before being noticed by most diners.

Another study, this time looking at young children eating in a school canteen, found that they served themselves more food - and ate the majority of that extra food - when given adult size plates and bowls to serve themselves with. These plates were roughly twice the area of the usual size plates and bowls.

Nudging can have an impact

Looking across all seven areas, Cadario and Chandon found an average positive impact from the nudges roughly the equivalent of eating 124 less calories or 8 teaspoons of sugar - or a small glass of red wine or a just under 3 jaffa cakes. Whilst this does not seem that much, consuming 120 or so extra calories per day every day can lead to substantial weight gain over the course of a year; as much as 6kg in 12 months. The new research was analysing eating occasions, not daily consumption so the daily effect of such nudges could be even greater. Public Health England recently found that on average, UK adults consumed approximately 195 extra calories per day, and overweight and obese adults approximately 320 extra per day. In addition, Cadario and Chandon also compared the average impact to studies looking at the impact of price reductions on healthy food and concluded that it was equal to a 10% price reduction.

Across the three areas, and seven types, two of the three areas were statistically significant. Action/behaviour-based nudges had the biggest impact (200 calories); plate and portion size changes had the largest impact overall (roughly 350 calories - the largest of any type of studies they analysed), while convenience enhancements had a more modest impact (around 180 calories). Affective/emotional cues also had modest, but identifiable impacts (120 calories). What’s significant about all these positive impacts from different types of nudges is the potential impact from combining them. For example, no study (to date) has tried combining reduced plate or portion sizes and convenience enhancements. This may have an even stronger impact.

Only the first area - cognitive-based nudges - had no significant impact. This area had only a tiny impact on eating behaviours, an impact which was not statistically significant, particularly for descriptive labelling such as calorie and nutrition labelling. This is particularly worrying, given the UK government’s recent announcement to tackle childhood obesity by stipulating that restaurants need to include calorie labelling. However, it may still be worth keeping an eye on this one given the behaviours of the consumers of the future - millennials.

A 2017 Euromonitor survey found that millennials were the most likely out of any age group to ‘closely read the nutrition labels of food and beverages’ - given that this group tend to want healthier, more natural food and drink.

They also found that it's a lot harder to nudge people to eat healthily than it is to nudge them to stop eating unhealthy foods. Impacts were generally larger for initiatives that nudged people to eat less or no unhealthy food, but researchers aren’t sure of the cause behind that. Americans also had a larger capacity to be nudged than citizens of other countries, although it’s not clear why, flagging a need to trial the more successful types of nudges in other countries rather than the US. In the future, we also need to run more trials in grocery stores and supermarkets, as well as in cafes and restaurants, to be able understand how to have maximum impact on a consumer’s food purchasing journey.

Overall, this latest analysis shows that some types of healthy nudges do work and are highly worthwhile, particularly as they are so simple.

What appears on first glance to be small tweaks and almost unnoticeable changes have a real potential to have significant impact on society. Once again in this final article we show how small changes can make a big difference.

BE 360 - How Behavioural Science is positively impacting our lives

This is the last in our BE 360 series of articles which takes readers on a 360-degree tour of how behavioural science is transforming our lives 24/7. You can find our complete series below:

- BE debt free faster - How BE inspired interventions are helping people to reduce debt faster

- How BE helps us to live healthier lifestyles

- How BE is nudging us to be a more giving society

- How much do you bend the law?

- What's up doc?

- Money matters: How behavioural science is helping to improve everyone’s financial future

- The BE Police

- Nudging travel energy consciousness

- Nudging our white coats

- We don’t need no education

- Using behavioural insights to make cities more people friendly

- Stopping our taps running dry

- Nudging healthy eating: what really works to help us eat more healthily

The positive impacts of BE on our lives has only just started and we should all embrace this learning and energy to propel us forward and to tackle new challenges!

Next month we’ll begin a new series looking at the latest developments and new findings in the ever-growing field of behavioural science!

Sources

- Cadario, R., Chandon, P., 'Which healthy eating nudges work best? A meta-analysis of behavioural interventions in field experiments', Working paper, May 2017; and presentation by Cadario at SJDM 2017 in Vancouver.

- Bollinger, B., P. Leslie, A. Sorensen. 2011. Calorie posting in chain restaurants. Am Econ J Econ Policy. 3(1) 91- 128.

- Levy, D.E., J. Riis, L.M. Sonnenberg, S.J. Barraclough, A.N. Thorndike. 2012. Food choices of minority and low income employees: A cafeteria intervention. Am J Prev Med. 43(3) 240-248.

- Hoefkens et al, ‘Posting point-of-purchase nutrition information in university canteens does not influence meal choice and nutrient intake’ American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2011

- Dayan, E., M. Bar-Hillel. 2011. Nudge to nobesity ii: Menu positions influence food orders. Judgment Decision Making. 6(4) 333.

- Gamburzew, Axel et al. “In-Store Marketing of Inexpensive Foods with Good Nutritional Quality in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods: Increased Awareness, Understanding, and Purchasing.” The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 13 (2016): 104. PMC. Web. 10 July 2018.

- Hanks, A.S., D.R. Just, B. Wansink. 2013. Smarter lunchrooms can address new school lunchroom guidelines and childhood obesity. J Pediatr. 162(4) 867-869

- Perry, C.L., D.B. Bishop, G.L. Taylor, M. Davis, M. Story, C. Gray, S.C. Bishop, R.A.W. Mays, L.A. Lytle, L. Harnack. 2004. A randomized school trial of environmental strategies to encourage fruit and vegetable consumption among children. Health Educ Behav. 31(1) 65-76.

- Rozin, P., S. Scott, M. Dingley, J.K. Urbanek, H. Jiang, M. Kaltenbach. 2011. Nudge to nobesity i: Minor changes in accessibility decrease food intake. Judgement & Decision Making. 6(4) 323-332.

- Diliberti, N., P.L. Bordi, M.T. Conklin, L.S. Roe, B.J. Rolls. 2004. Increased portion size leads to increased energy intake in a restaurant meal. Obesity. 12(3) 562-568.

- Freedman, M., and Brochado, C., ‘Reducing Portion Size Reduces Food Intake and Plate Waste’ 2010, Obesity, 18(9) 1864-1866

- DiSantis et al ‘Plate Size and Children’s Appetite: Effects of Larger Dishware on Self-Served Portions and Intake’, 2013, Pediatrics. 131(5) e1451-e1458

- Public Health England, ‘Calorie reduction: The scope and ambition for action’, March 2018

- Financial Times, ‘How millennials’ taste for ‘authenticity’ is disrupting powerful food brands’ 19th June 2018