#fakenews is a cultural blob that incorporates the feelings that everyone is lying, that shouting is truth and that feelings trump facts. It’s not well-defined, it’s not easy to poke at, that’s probably its power. But I thought it was worth exploring because we’re all in the business of explanation and persuasion and we’re doing that in a #fakenews world. And, of course, it’s all our fault.

1. We Are The Problem

Ev Williams knows quite a lot about the internet. He was in at the invention of Blogger and Twitter. He did an interview with the New York Times recently and diagnosed the #fakenews problem like this: ”The trouble with the internet, Mr. Williams says, is that it rewards extremes. Say you’re driving down the road and see a car crash. Of course you look. Everyone looks. The internet interprets behavior like this to mean everyone is asking for car crashes, so it tries to supply them.” What Mr Williams doesn’t have to say, but it’s worth reminding ourselves of, is that the mechanism that drives this behaviour is advertising. The internet rewards attention with cash because of advertising. We built that model. We didn’t build a model that rewards high quality content or trust-worthy media owners or decent editorial environments. We attempted to abstract all that away, reducing our metrics to disembodied qualities like ‘eyeballs’ and ‘clicks’. We forgot that there were people involved and that our decisions had consequences. It’s understandable, of course, we tried to create a complex, global, interactive media ecology from scratch in a dozen years or so. We were bound to get it wrong. Print newspapers have had several hundred years to sort it out and they’re not much better. But, this is where we are. Advertising is what makes it economically sensible for smart people in Macedonia to make up lies about US politics and put them on the internet.

2. It's Just Going To Get Faker

The problem now is that all the news is just going to get faker. Machine learning is not far from making it trivially easy to generate, for instance, video of anyone saying anything. Look at the University of Washington’s Synthesising Obama project; they can take a piece of audio combine it with a bit of talking head video and make an entirely plausible video of Obama saying a thing he never said. That, of course, has been possible for a while with special effects and clever technicians, the problem now is that we’re a few years away from it being a 69p app on your phone, something you can do to anyone. This will be an annoyance for politicians and celebrities, but they’ll be able to prove the untruth through detailed, probably expensive evidence of being somewhere else at the time. But what happens when someone uses it to produce evidence of the staff in your shop abusing them? or of a sales person promising them an impossible deal? What happens when technology weaponises fraud and abuse? It’s going to be a mess.

3. The opposite of Fake is Detailed.

...And Boring. And Not Short Sentences.

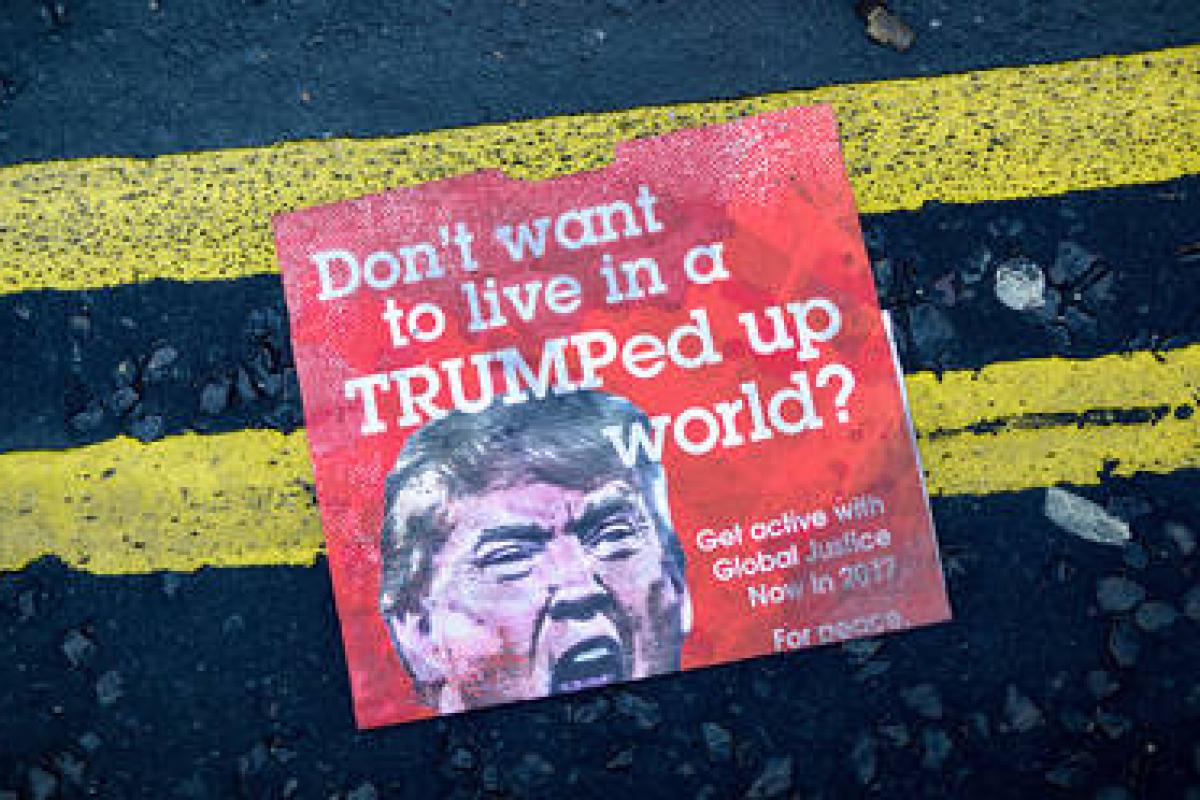

We’re also going to have to abandon some of the rhetorical styles of sales and marketing. I used to work at Nike’s advertising agency and we use to joke that our key advantage was that we could ‘fake authenticity’ better than anyone else. There are, or were, clear, well known stylistic, rhetorical flourishes that made communications feel ‘true’. Simple, blunt language. Plain-spoken-ness. Regular demotic speech. Short sentences. But that’s how Trump talks too. That’s how #fakenews is spread. That’s what Goop do. If you want a ‘trusted brand’ you’ll have to a) (obviously) be trust-worthy and b) be detailed and precise about explaining yourself. It will feel too long and too boring, it will feel like too much work. But the slogans aren’t working. Not everyone will read the detail but they’ll like to know that it’s there. Hopefully this will spell the end of the empty brand manifesto. All those short sentence. Saying nothing. At length. With that music.

4. Pay Attention to the Bottom of the Page

Part of that detailed work will be at the bottom of your website where the caveats lurk. Clear, honest Terms and Conditions might be the best way to fight #fakenews. You’re probably rewriting them anyway because of GDPR so perhaps you could pay extra attention and really make them sing. Innocent smoothies made the words on the back of the bottle a competitive landscape, maybe GDPR will do the same for terms and conditions.

(If you want to get a head start on thinking about this stuff have a look at what the design consultancy IF have put together)

By Russell Davies, Chief Strategic Officer at BETC, a contributing editor for Wired and a relentless mucker-about on the internet.

Follow @fourthingsabout on Twitter for a stream of links and articles related to this quarter’s topic.