Shortly before the 2016 US presidential election, a nuclear bomb hit the Trump campaign. A video showing Trump making sexist remarks about women was leaked. What happened next was more puzzling than the video itself: even among female supporters, Trump’s approval ratings didn’t really move much. Facts, it seems, aren’t always enough to change people’s minds. But what does?

Often, after a talk, someone will say to me: “I’d love to try what you suggest, but my boss has very strong views.” The biggest roadblocks to company progress are stubborn beliefs. Every manager can tell stories of when the best facts weren’t good enough to tip people over.

In 1977, Digital Equipment Corporation’s CEO Ken Olsen was absolutely convinced when he said: “There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home.” Nokia’s leaders, at the turn of the century, believed the iPhone was a niche product. Neither Olsen nor Nokia’s management wanted to pay attention to facts that would prove them wrong. We all know where it ended. Strong beliefs exist in virtually every company and every department. Be it female quotas, performance-based pay, or simply the question of whether TV advertising is right. Beliefs often trump facts.

As a leader, running up against strong beliefs can mean anything from annoying you to derailing the company’s most important future initiatives. Fighting confirmation bias When colleagues reject our ideas, our natural reaction is to reiterate our points or, even better, to counter with insights: ‘the test results have shown…’, ‘customers have told us…’, ‘a new study proves…’. In most cases, this evidence strategy works. Powerful facts should be your weapon of choice. Yet, there are cases when arguments and facts will not do the trick. I’m sure you have heard about confirmation bias: we tend to seek out information that confirms our pre-existing views and reject information that contradicts them. Trump’s opponents, for example, took the sexist video as further proof of his inability to lead the country, while his fans saw it as evidence of an authentic leader (‘just a normal bloke’).

Having a view on things is actually a great thing. It allows you to stroll along a supermarket aisle without going crazy thinking: “Is this safe to eat? Will this make me sick? You have pretty much made up your mind that most supermarket food is safe or, worst case, will make you fat. Strong beliefs help us simplify so we can survive in this complex world. But that simplification makes us – and all our colleagues – stubborn too. We have a tendency to overestimate what we know (yes, you too!)

To change others’ strong beliefs, however, that overconfidence is the critical loophole. Researchers at Yale University undertook a fascinating experiment. They asked students to rate how well they understood everyday items, such as flush toilets or zips. On average, the students gave themselves high marks, saying they understood these things well. Next, the researchers asked the students to write step-by-step explanations of how these devices work, and then rate their understanding again. Suddenly, the self-assessments dropped (it seems we even don’t understand day-to-day items like zips as well as we think).

What can the zip case teach leaders? It tells us that confidence in one’s strong position can erode when we explore the position in much more detail.

Deep questioning

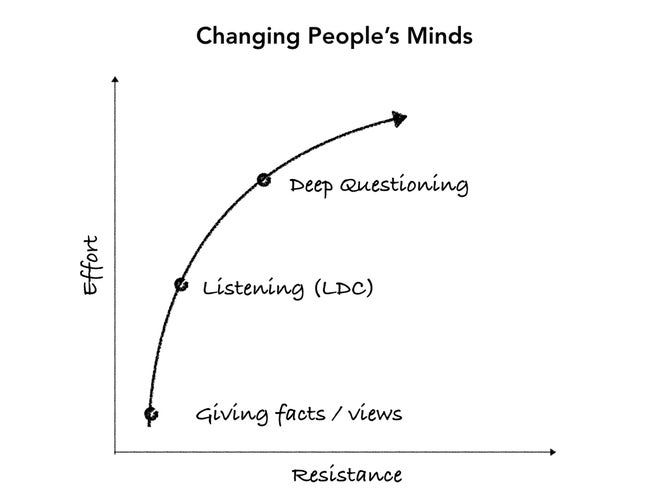

All decent leadership books have a piece on listening. If you haven’t already, read that listening section this week. In any change project, listening to people is key – before you make decisions, and afterwards too.

I call this process LDC: listen, decide, communicate. LDC is how The Australian newspaper’s former marketing director Ed Smith convinced his colleagues to introduce successful paywalls. And LDC is what former BT marketing director David James did to convince the brand’s management to fast-track the launch of the BT Sport channel, grabbing the market before competitors could.

By giving people a voice and making them a part of the solution, LDC turns pushback into problem-solving.

But every so often you’ll hit a wall of strong views – the moment when listening and debating will not work. Imagine, for example, your boss suddenly believes sponsoring Formula 1 is a marvellous idea for your brand (even if facts show it’s a waste of money). That is when your best bet is another powerful technique: ‘deep questioning’. It means asking the person to explain step-by-step how things would play out. In the example above, you would ask your boss for details on how that sponsorship would work, how much return it would generate for each dollar spent, how exactly a logo on a car will trickle through to how people shop, how sponsorship compares favourably to in-store promotions, etc. Like with the zipper, forcing your opposition to detail how things will play out will help them see the aspects they (or you) haven’t thought about. And that is when the door slips open for your facts to come in again. “How, exactly?” is your most powerful question. Deep questioning is listening on steroids. It’s helping people see the flaws in their own thinking, so facts have a chance again. Sure, deep questioning isn’t a silver-bullet solution when you hit push-back. But it’s your best bet for tackling the really wicked barriers to change: people’s strong beliefs. You have only pushed the limits when people say “stop listening to me”.

Thomas Barta is a marketing leadership expert, speaker and co-author of ‘The 12 Powers of a Marketing Leader’ with Patrick Barwise.

This article originally appeared in Marketing Week.