Emotions have, of recent times, been the marketing hot topic, with increasing and exciting evidence that emotionally engaging communication correlates with positive impact on sales.

This correlation is intuitively plausible and creatively liberating, which is why this notion is heavily embraced by marketing and agencies.

Moreover, it has rapidly given rise to a whole range of new tools designed to help marketers measure the emotional impact of their communication through, for example, facial expression, biometrics or EEG.

As much as we may be excited by the correlation and be naturally inclined to believe in the ‘emotion is everything’ narrative, we also know many confounding cases where “they love the ad but it is just not selling…”. Take, for example, the much-lauded Budweiser Puppies ad which ran in the 2015 SuperBowl.

According to Jorn Socquet, the US VP for Marketing at A-B InBev, while everybody loved the puppies “they have zero impact on beer sales”.

Rigorous scientific analysis provides a more precise understanding of emotions and of how exactly they relate to purchase decisions.

In this three-part series we take a deeper look at the science of emotion, why emotional communication can help to sell and how emotions really relate to purchase decisions. This level of precision is important because, if marketing is ultimately about shaping behaviour in favour of our brands, the winners will be those who best understand the true dynamics of behaviour and how to use this to brief for effective communications.

In this initial part, we explore the science that helps to explain how and why emotionally engaging communication can engender positive effects.

Let us start with the basics

Most of us think we have a pretty good idea of what emotions are – but what are they from a scientific perspective?

First and foremost, emotions are a physiological response to something we experience or anticipate. Our brain continuously tries to make predictions about the world around us in order to survive.

This helps prepare our bodies to cope with the upcoming situation by releasing neurotransmitters, adapting heart-beat, regulating blood pressure and muscle tension accordingly. Hence, the way emotions are measured in science is to measure these physiological responses, for example, heart rate, sweat and respiration. These affective physiological responses are automatic, fast and very basic to prepare us for fight or flight.

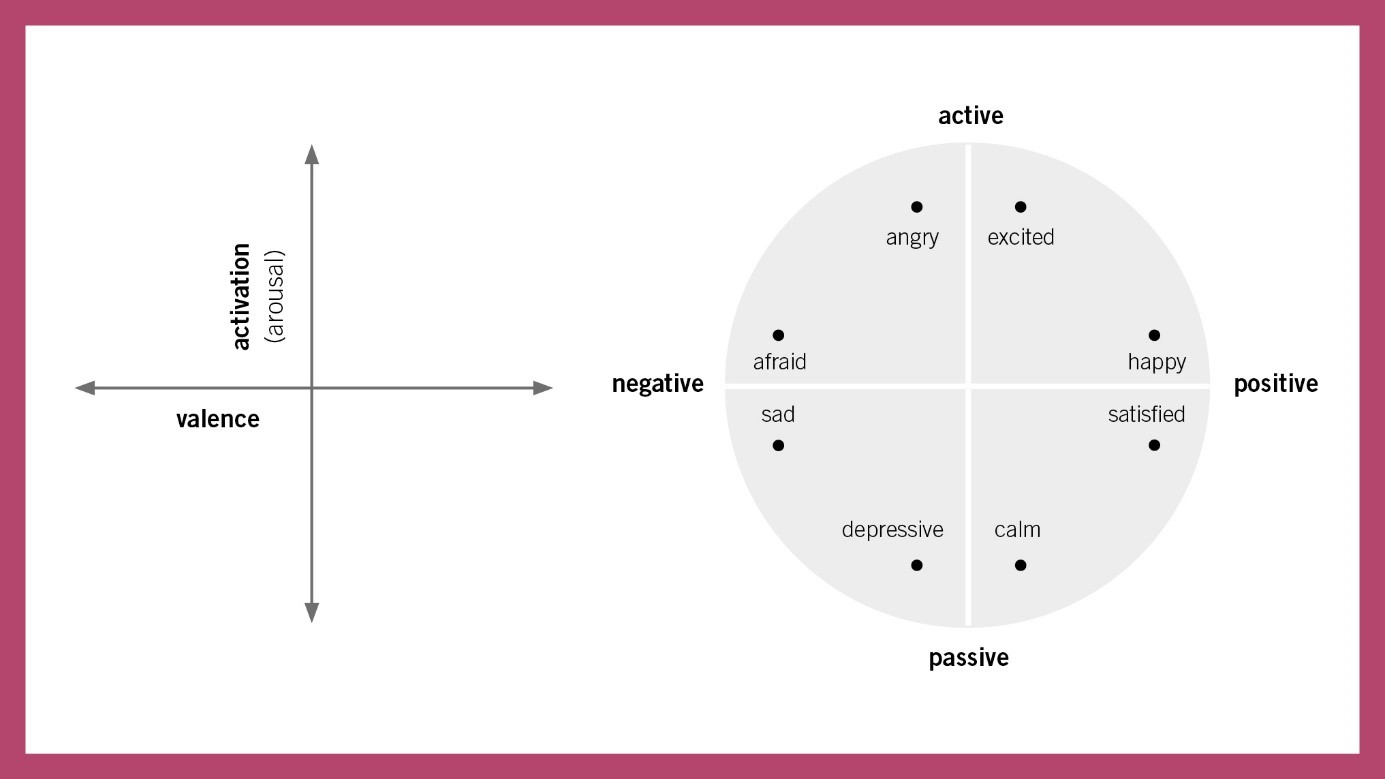

There are two physical dimensions to emotion:

- Arousal – intensity of the body’s physiological response

- Valence – evaluation of whether something is positive or negative

We like to try and make sense of these physiological sensations and so we construct ‘feelings’ based on the emotional response.

We attribute different feelings to the same emotional response based on the specific situation we are in, our experience, personality and our cultural background.

The feelings are labels we attribute to the emotion experienced (Barrett, 2017). We may frame and describe these feelings as ‘love’, ‘hate’, ‘jealousy’, ‘anger’ or other descriptors, but the underlying emotion is driven by only the two dimensions of arousal and valence.

Basal effects occur along the dimensions of valence (good, bad) and arousal (active, passive).

So how does emotion drive communication effectiveness?

Firstly, emotional response evolved as a mechanism to prepare our body for fight or flight.

If we are in a state of high arousal, our attention span increases and our senses are sharpened to be able to deeply process the object that triggers that arousal. However, sometimes an ad evokes high arousal, but no one remembers the brand - why? To leverage the potential of the arousal the brand/product needs to be the agent that triggers the response.

If emotional response is not linked to the brand, the ad might be remembered but not the brand because it is not instrumental in activating the emotional response.

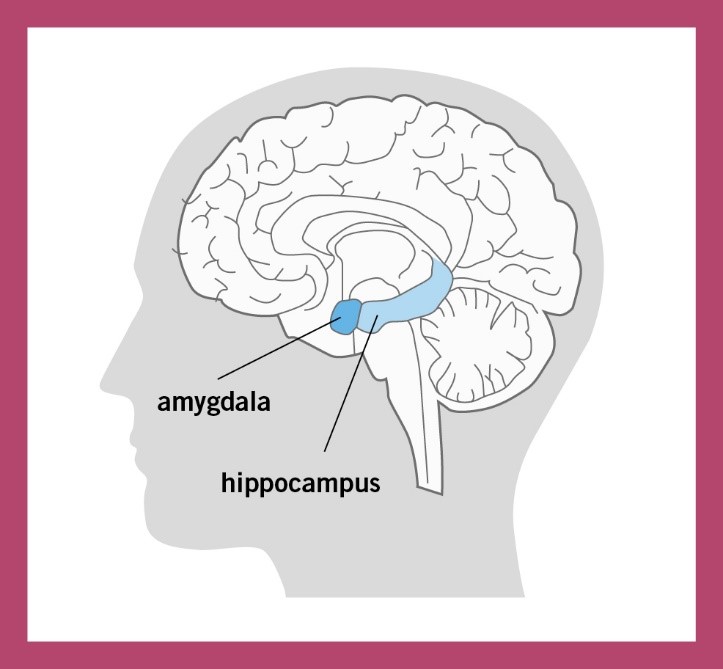

Secondly, due to its deeper processing, emotionally engaging communication is more likely to be remembered. To understand this positive impact on recall we need to look at the brain’s geography. The hippocampus is a brain structure that manages what we store and where, and it is positioned right beside the amygdala – our emotional centre.

This shows the relationship between emotional response and memory formation: to survive, and to optimise future decisions and actions, it was especially important to store and remember those objects and situations that evoked a strong emotional response. Hence, we are more likely to store episodes (e.g. TVCs) and objects (e.g. brands) if they are delivered with high arousal.

This shows the relationship between emotional response and memory formation: to survive, and to optimise future decisions and actions, it was especially important to store and remember those objects and situations that evoked a strong emotional response. Hence, we are more likely to store episodes (e.g. TVCs) and objects (e.g. brands) if they are delivered with high arousal.

So, if an ad is emotionally engaging we are more likely to store it, contributing to the recall of the ad and also increasing the mental availability of the brand (assuming the brand is correctly assigned to the ad). Thirdly, arousal is a key predictor of sharing creative communication. The higher the arousal, the more likely people are to share. Hence, emotionally engaging ads are more likely to be shared and this can greatly increase reach (Falk, E. et al. 2013).

What about valence?

The valence of our experiences with the brand – be it via usage or watching an ad – becomes part of the brand’s associative network. Therefore, a communication that evokes a positive emotional response is helpful in building a positive attitude towards the brand. The research cited above also shows that communication creating positive valence is more likely to be shared than negative.

So emotionally engaging communication can be more effective. However, despite this, the notion that ‘emotion is all that matters’ has significant limitations.

Arousal and positive valence are fundamental but also very basic dimensions. They do not help to differentiate our brands and products. Valence only provides a basal evaluation (good vs. bad) and hence only provides basal differentiation between brands.

To recap, communication that evokes an emotional response helps us to process and remember an ad and encourages us to share it with others.

So far, so good. However, some emotional ads sell, whilst others do not – why? In the second instalment, we will take a closer look at decision-making as a basis to help to explain this...

By Phil Barden, managing director, DECODE marketing ltd