Author, brand consultant and executive at The Value Engineers, Giles Lury, says we're in a period of growing activism not since seen the '60s and it's affecting the choices people make about products and brands

It seems like the marketing world is on a mission to replace vision with purpose.

A secondary but linked debate has started around the adoption of principles rather than the use of values. If both these changes happen, then two of the traditional pillars of any brand positioning will have been replaced so it’s worth pausing and considering what is meant by each of the new terms, what are driving the changes and what it means for companies adopting them.

On purpose

As with most marketing terms, there are a variety of definitions of brand purpose, but most revolve around inspiration, aspiration and higher order benefits for society and the environment. Jim Stengel in his book Grow said a purpose was, “A business’s essential reason for being, the higher-order benefit it brings to the world” Roisin Donnelly, P&G Northern Europe Brand Director, highlighted the need for longevity and breadth saying, “Purpose isn’t about having one tactical campaign with a charity or an agency – it has to be big, inspiring, simple and memorable. It has to inspire every single person in your company, as well as shareholders, stakeholders and agencies.”

Analysis, we at The Value Engineers conducted, on the 100 most valuable brands (according to Interbrand) highlights some interesting findings. The purposes we saw on the whole reflected these definitions of purpose. They were more ‘big picture’ e.g. Allianz “to enable people to move on and up in life and business.” Some brands we reviewed aren’t planning on replacing their vison/mission with a purpose but rather using both terms. This is a reflection of the different perspectives they take.

Why?

There would appear to be three factors that are driving this change. The first is the increasing recognition that the world is facing some huge challenges, from global warming to continuing poverty; there are social injustices and political and social tensions. These are no longer matters that just concern scientists, academics and analysts, they are increasingly part of a growing global social conscience. Whether it is teenage influencers like Greta Thunberg, social movements like #metoo. We are in a period of growing activism and its already at a level not seen since the 1960s. It’s affecting the choices people make about products and brands whether that’s the amount of red meat they eat or the number of flights they take. It’s also starting to impact on their brand choice to a much greater degree than before. According to a 2017 study by Cone in the US, 87% of consumers say they would buy a product because a company advocated for an issue they care about

The second reason is that marketing is a young person’s profession and the new generation of marketers and indeed many of the older ones too, have the same concerns. Mark Ritson went as far as to say that “this current obsession with brand purpose stems, I believe, from marketers that are unhappy with the prospect of selling stuff.” He went on to say, “At some point in the last 10 years it became uncool to take professional pride in making splendid products, satisfying customers and generating significant profits.”

The third reason is that there is a body of evidence that suggests it pays to be good. In ‘Grow’ Stengel sets out evidence that “Brands build value, whether in consumer products or professional services. Evidence suggests that over a 10-year period, businesses with clearly defined and consistently executed brand purposes deliver on average 400% better returns to shareholders”

The era of higher ideals in business | Jim Stengel

Other studies have shown that employee stay longer in a company, customer retention is higher, and people are more likely to recommend brands that have a clearly defined purpose.

But…

All this might suggest that purpose is the way forward but like many new ideas it seems like adoption is slower than might be expected. Our study of the Top 100 most valuable brands showed that only 14 had purposes. This compares with 36 that had visions, 48 that had missions and 60 that had visions and/or missions. There was a tail of 33 that had none of them or chose not to publish one. The final challenge with regard to adopting a brand purpose goes back to Roisin Donnelly’s definition of purpose and the idea that a purpose isn’t just for a campaign but for life.

The problems here have been two-fold. The first is that there are numerous occasions when brands and the companies that own them have had to choose between their purpose and short-term profit and too often they have bent or broken their promises rather than fail to deliver the returns the city or stakeholders demand.

The other is that some of the campaigns used by brands to promote their purposes have come in for criticism and even backlash, the most famous, or infamous, of which was probably the Kendall Jenner Pepsi ad.

Why Kendall Jenner's Pepsi ad is so controversial - Washington Post

Principled

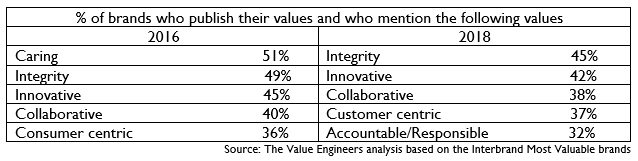

Our review of the brand positioning of the most valuable brands over the years has looked at not only their mission and visions but also their values. The conclusion from these studies is that a high percentage of brands all gravitate towards the same values. (see table 1 below - click image below to expand it)

While these values aren’t ‘wrong’, the chosen values tend to be motherhood and apple pie statement, ones that no-one will disagree with and which boards can agree to agree on. I amongst others have therefore been arguing that values have become devalued and that they don’t play one of the key roles required in a good brand positioning. They don’t provide meaningful distinctiveness from one brand to another.

The alternative is for a brand to define their beliefs, their principles and/or their ‘philosophy’. A good principle should define a non-negotiable stance that a brand takes, something it might campaign for, something that helps employees know how they should act. It is generally a longer description of the idea rather than the 1 or 2 words used for a value and allows for a brand’s personality to shine through more. This helps further differentiate brands. The strength, but also the difficulty with them though, is that a true principle isn’t a principle until it costs you money.

So as with the adoption of purposes, while there has been an increase in the number of brands who cite principles, values remain more prevalent. Out of the top 100 most valuable brands 56 cited Values, while 9 talked to Principles, 7 to Philosophy with 15 having Principles and Philosophy. 35 do not formally mention any values. On average brands mentioning values have 4.8 of them, while those mentioning principles have 5.

So, what does the future hold?

The world isn’t going to stop changing. The problems it is facing won’t disappear overnight. Societal pressure on brands is going to increase. The need for brands to express their true purposes and their philosophies is only likely to grow but with that will come with pressure to ensure they deliver on them. Purposes will need to be clear, but not necessarily lofty. Philosophies will need to be based on truly distinctive principles worth fighting for and backing, not just comfortable platitudes.

It will be an interesting time to be a marketer.

This article appeared in issue 4 of Marketing Society members' publication EMPOWER. View the archive here.