We all know people around us who can be impulsive and shortsighted. But are there some groups or demographics that are more likely to have these traits?

Over the past decade, psychologists and neuroscientists have been analysing people's decision-making to see if there are differences across generations. Their research has generated a wealth of new understanding and there is now weighty evidence to suggest that on average, the stereotype that younger people – teenagers up to young adults in their mid-20s - tend to prefer to enjoy gains today rather than later is true.

Younger people really are more likely to be what behavioural scientists call ‘present biased’ or affected by the 'power of now' - preferring immediate but smaller rewards over delayed but larger ones.

But it is neuroscience which has uncovered the likely mechanism behind this behaviour. And it is not simply that the young are just more impulsive and lack self-control.

The real cause is that teens' and young adult's brains have not yet fully developed. The neural structures and connections in their brains are still flexible at this age, enabling them to keep on learning how to make good decisions, gathering the life experiences that teach us when it is often better to delay rewards and wait.

Older people have the luxury of many years of decision-making experiences to draw on. They have learnt – not only through trial and error but also the welcome arrival of some delayed rewards, such as gains from long-term financial investments and accumulated savings - that it is often better to sit patiently and wait than to dive in immediately.

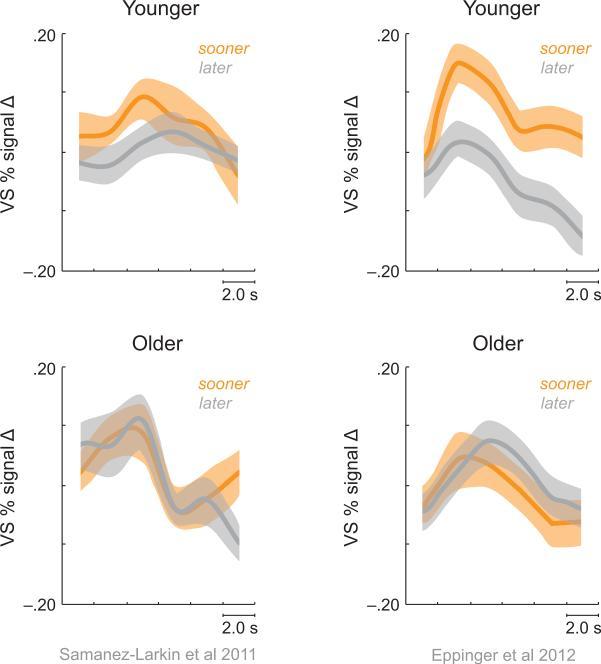

This learning is driven by dopamine - a neurotransmitter in our brains. Using brain scanning technology such as fMRI, neuroscientists* have found that as dopamine flows through our brains, a region called the ventral striatum shows greater activity when we receive a reward than when we incur a loss. Yet there are some notable age-based differences in these activity levels (also see figure below):

- Young people show greater activity in the ventral striatum region in response to immediate rewards and less activity for delayed rewards.

- Older people, however, show an equal response in activity levels to immediate and delayed rewards; they are less sensitive to a delay in a reward and more content to wait.

Figure 1: Differences in brain activity between young and old when faced with immediate and delayed rewards

- Top row: Younger people show greater activity in the ventral striatum when offered an immediate reward. This illustrates why they tend to be more present-biased. The orange area (immediate rewards) is higher than the grey area (delayed rewards) showing different activity levels.

- Bottom row: Older people show equal activity in the ventral striatum when offered an immediate or delayed reward. Here the orange and grey areas overlap indicating equal activity.

Neuroscientists first speculated that younger people’s brains were less developed simply because they were still ‘work in progress’ and relatively immature. Yet many scientists now believe that our brains delay their final stages of development to allow us to remain flexible in our thinking and learning and open to novelty and risk, necessary in propelling us through the difficult transitional stage of leaving home and making our own lives, distinct from our parents.

Conclusion

So next time your teenager does something you view as reckless, give them some space and pause to reflect on this new understanding. It helps to explain why they seem to live for today more than their older peers and end up in situations which they could perhaps have avoided with a little forethought.

The findings also have clear implications for how we might best communicate to different age groups and get their attention. For example, younger people may be more likely to respond to messaging about the prospect of immediate rewards; older people may be content to be more patient.

*Sources: Samanez-Larkin et al "Age Differences in Striatal Delay Sensitivity during Intertemporal Choice in Healthy Adults" Front Neurosci. 2011 Nov 16;5:126 and this article here.

David Dobbs, “Beautiful Brains” National Geographic, October 2011

Read more from Crawford Hollingworth in our Cluhouse.