We're not always very disciplined when it comes to taking medication; whether it’s to cure an illness, prevent one from worsening or to manage a chronic condition. It’s estimated that around half of patients forget to take their prescription medication. As one patient commented “My three months’ supply of Simvastatin seem to last me about six months…”[1] This is not only detrimental to a patient’s long term health, but it also increases healthcare costs since, if medication is not taken correctly, conditions can worsen or lead to complications. Around 20-50% of patients fail to take their medication as prescribed and this impacts on healthcare systems around the world to the tune of billions of dollars[2]; in the US alone, experts estimate that the bill for non-adherence runs close to $300 billion dollars a year.[3] So naturally, healthcare professionals are particularly interested in analysing this problem and looking at ways - ideally cost effective ones - through which to improve medical adherence.

Using behavioural economics to understand medical adherence

The behavioural sciences can help us to understand this issue and can also provide us with a rigorous, strategic framework with which to analyse medical adherence or non-adherence. We can use behavioural economics to understand why some people are great at following doctor’s orders whilst others are not so good. Behavioural economics tells us that to analyse behaviour effectively we need to consider different contexts, taking into consideration the environmental context at different times, the social context, as well as the many individual cognitive biases which can affect behaviour. These frameworks and concepts provide a powerful way to understand the architecture around current behaviour. They also allow us to hypothesise reasons for non- adherence around this model.

One reason for non-adherence in the medication context might be our tendency to put off unpleasant things until tomorrow. We prefer to enjoy today. Behavioural economists call this time inconsistency and discounting the future, we like to call it the ‘power of now’. Because medication often has short-term, unpleasant side effects or is a hassle to take and can interrupt your plans, people sometimes choose to defer taking it and can suffer the consequences of poor health as a result.

We are also comfortable with the status quo and dislike change in our daily lives and routines. A medication programme is sometimes a very complex affair; for example Parkinson’s, heart disease or type 2 diabetes all require considerable medication management, not only in the taking of the drugs themselves but also the effort required to check in with doctors, to collect prescriptions and pick up or buy medication. Consequently, we can suffer from inertia preferring instead to keep our lives running on the same routines.

Linked to this problem is the hold our habits have over us. Our habits are deeply engrained in our brain and muscle memory and it can take as long as two months or even more to build new ones, even if they're only small. Taking a complex programme of medication over the long term involves creating new habits and adapting our existing habits and routines to fit in with the programme's demands. If we don’t manage this, we are likely to forget to take our medication at the right time and frequency.

We might also sometimes fail to take our medication because of situational reasons or changes in the environmental context around us. We might be great at remembering to take our medication at home but forget when we are travelling away, where there are not the same cues and triggers to remind us.

Thinking that other people are bad at taking medication might also make us sloppier when it comes to remembering to take our own. Research has shown that perceptions of social norms can be strong influencers on our behaviour, in all sorts of contexts; from what we eat, to how much we exercise, to how much we save rather than spend.

Behavioural Economic solutions to better adherence

Behavioural economics can not only help us to understand patient behaviour, but can also provide us with a toolkit with which to develop potential solutions to nudge and steer behaviour and ensure patients are on track with their medication. Once you understand the behavioural architecture in operation then you can start thinking from a richly informed perspective how to influence it by using the different BE concepts at your fingertips.

There are already some innovative solutions which use behavioural economics to improve medical adherence. For example, a US company has recognised the problem of forgetfulness and lack of routines and habits in taking medication and launched GlowCaps – an intelligent lid for prescription bottles.[4] The plugin reminder light and cap connect to the AT&T Mobile Broadband Network, giving both light and sound indicators for any scheduled medications, vitamins and supplements. The device is programmed with the exact prescription and the cap glows progressively more intensely as soon as the patient misses the deadline for taking the medication (see image). If the patient still fails to act, it plays a tune, and if this doesn't prompt action it will send a text reminder or recorded message to their phone. At the end of each week and month, Glowcaps emails the patient a progress report telling them how they’re doing - which people often seem to respond to out of sheer competitiveness with themselves. As one user says ‘it’s almost kind of like a game’.[5] Not only are these great behaviour prompts, but over the long term could actually help to instil the habit of taking medication regularly. There is also no room for ‘inventing the truth’ to doctors as the GlowCap sends an automatic print out of patients' medication consumption to their doctors each month too, or indeed, to anyone who might need to see their adherence record. One patient arranged for his reports also to go to his wife to help keep him on track!

Another study run by researchers Kevin Volpp, George Loewenstein et al, conducted a smallscale experiment to see if they could use lotteries to improve medical adherence. They gave a special pill box with a daily reminder feature to volunteers on Warfarin medication. If volunteers opened up their pill box according to their prescription, they were entered into a daily lottery with a 1 in 5 chance of winning $10 and a 1 in 100 chance of winning $100 (pilot 1) or a 1 in 10 chance of winning $10 and a 1 in 100 chance of winning $100 (pilot 2). The results were encouraging. The mean proportion of incorrect pills taken fell from 22% before the trial to around just 2% for both pilots.[6]

Another study run by researchers Kevin Volpp, George Loewenstein et al, conducted a smallscale experiment to see if they could use lotteries to improve medical adherence. They gave a special pill box with a daily reminder feature to volunteers on Warfarin medication. If volunteers opened up their pill box according to their prescription, they were entered into a daily lottery with a 1 in 5 chance of winning $10 and a 1 in 100 chance of winning $100 (pilot 1) or a 1 in 10 chance of winning $10 and a 1 in 100 chance of winning $100 (pilot 2). The results were encouraging. The mean proportion of incorrect pills taken fell from 22% before the trial to around just 2% for both pilots.[6]

Another trial using a suite of ‘nudges’ in letters to patients has also had remarkable success. The behavioural economics research consortium ideas42 partnered with the Medicaid Leadership Institute and a team from Oklahoma Healthcare Authority, SoonerCare to implement a randomised controlled trial for diabetes patients. Letters were sent out to 2,500 patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes who had not yet begun statin medication, despite their condition. Patients received one of four interventions:

- One group received the basic letter encouraging them to call their doctor to arrange a cholesterol check and discuss a statins prescription

- A second group received a $5 gift card with their letter which could be activated after attending an appointment

- A third group received a letter which had been redesigned to include a suite of ‘behavioural nudges’ such as making the consequences of remaining untreated more salient or including post-it note reminders

- A fourth group received both the nudge letter and the $5 incentive

The results were astounding. Those who had received the behavioural nudge letter (the third group) saw a 78% increase in response compared to the control group. The team are now looking into how to develop this initiative further.[7]

TB is also being tackled by providing short term incentives to achieve a long term cure for patients with the disease. The behavioural problem lies in the fact that although TB is a very treatable disease, simply requiring a course of medication, the treatment is a long, complex affair which has unpleasant side effects initially, often causing patients to stop their medication at an early stage or to stop prematurely as soon as they begin to feel better. So the culprit is time inconsistency or power of now – we prefer comfort now rather than comfort and health later. Ideally, treatment can be managed through directly observing and caring for the patient – but this is expensive and difficult to implement in developing countries or for poorer patients. So Amit Srivastava, a microbiologist at the Children’s Hospital, Boston has devised a cell phone based system using incentives to increase adherence. He provides TB patients with a month’s supply of medication – together with specially designed urine tests. When patients take the urine test, coloured dots appear, revealing a numerical code that the patient simply texts to their healthcare provider. If the pattern of dots indicates metabolites of TB drugs in the urine, the patient receives an automatic reward of free cell phone minutes. So the system helps to fight time inconsistency with an instant reward. And it is very efficient – one healthcare worker can follow 50 patients and the only technology needed is a cell phone. No internet or visits are required.

In general, behavioural interventions show the most promise compared to more standard approaches such as informational or social interventions. A meta-analysis of 37 randomised controlled trials looking at improving medical adherence found that behavioural interventions generally had the greatest impact on adherence, especially those which looked at simplifying dosage demands from say, 2 doses to 1 dose per day, and those which provided monitoring and feedback, like the GlowCaps initiative described earlier.[8]

Other potential BE solutions

The few examples discussed above are really just the tip of the iceberg though. Behavioural economics is a powerful tool and a wide-reaching one too – there are over 90 identified cognitive biases; including social norms, peak end rule, availability bias, time inconsistency and commitment bias – and so there could be many more effective behavioural interventions which could have a real and dramatic impact on medical adherence.

We can start by simply looking at which behavioural economic interventions have worked in other sectors; encouraging voters to get out and vote, for example, or reducing energy consumption, or increasing pension contributions, and think about how these might be adapted for healthcare.

Research into what nudges people to get around to voting has demonstrated how committing to making a plan helps to meet our goals in a number of ways. We might have every intention of voting, but we often overestimate our ability to vote on the day. The Obama election campaign made great use of this research in the lead up to election day in 2012 and actively encouraged voters to ‘make a plan’ to vote. Similarly, the UK government has achieved notable success in a pilot aimed at getting people back to work which was implemented by the Behavioural Insights Team. They asked jobseekers to make a weekly plan detailing the specific actions they would take to find a job; whether it was to update their CV or to fill out an application form on a Wednesday morning. The same approach could be used to increase medical adherence. Making a plan can help us to achieve a goal or task (such as taking medication) by leveraging three different concepts from the behavioural sciences. The first is chunking: we think through the logistical aspects of meeting our goal, whether it is voting, getting a job or taking our pills and ‘chunk’ or break down the task into different parts. The second is commitment bias: by setting ourselves a defined task or goal, writing out a plan, we are likely to feel more committed to achieving it. The last are memory triggers: the plan creates the triggers in our memory that help us to carry out the right parts of the task at the right time. For example, if part of the plan to take your pill is to take it with a cup of tea, simply seeing the kettle will prompt and trigger your memory of the next step in your plan.

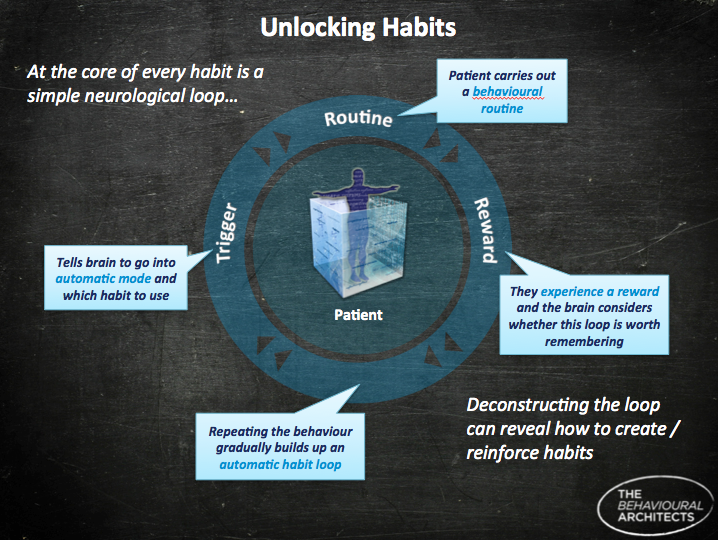

Cues like seeing the kettle also link to habit formation. Habit theory tells us that all our habits are linked to triggers and cues in our environment which send a signal to the brain to carry out a linked behaviour next (see image).[9] So turning on the kettle might give us a cue to pick up a mug and find the teabags. Or wheeling out our bike for our morning commute will also prompt us to pick up a bike helmet. These things happen automatically – our brains have been linking those actions together long enough to ensure that they now happen automatically. So what should we do when we want to create and cement a new habit?

- One way is to ‘piggyback’ the new behaviour of taking medication onto another existing habit like putting the kettle on, or perhaps brushing our teeth morning and night.

- Habits are also known to respond very well to little rewards. For example, we might go to the gym looking forward to the reward of how good we'll feel afterwards, or how we'll be able to enjoy a well-earned breakfast. Similarly, to encourage us to take our medication, we could also create an immediate reward like having a little square of chocolate to wash down the pill. In the same way, the ‘pee and text’ initiative for TB works because there is an immediate reward of cell phone minutes for taking the medication.

- BJ Fogg, based at the Persuasive Technology Lab at Stanford University, who is an expert in habit formation, recommends altering our environment to create cues and triggers to prompt action. He believes that the easier the habit is to perform the more likely it will be to stick. So rather than burying our medication in drawers or handbags, it might work better if we pin them to the fridge, or the bathroom cabinet, and keep a bottle of water handy to make it easier to take them. Again, this is partly why GlowCaps are effective since they create little cues and prompts to remind patients to pop their pills - they do the hard (remembering) work, in effect.

Another behavioural economics concept which has the potential to be a useful tool to increase adherence is to make patients more aware of social norms among patients with similar conditions. Both academic research and real life trials have shown that making people more aware of what behavioural economists call descriptive social norms (what others are doing) can increase adherence or change behaviour in all sorts of areas – from reducing electricity consumption and littering, to alcohol consumption and smoking. For example, the American energy software company Opower has found that showing households how their electricity consumption compares with that of their neighbours can lead households to reduce their own electricity consumption by 2% on average and up to 6% for heavy users. Their reports include statements like “You are ranked #41 out of neighbors like you" or "You used 19% more energy than your efficient neighbours". In health screening, the UK based Jo's Cervical Cancer Trust encourages women to go for a screening using the social norm message: "76% of UK women took up their invitation for cervical screening"[10] making sure that women are aware that screening is the norm and encouraging them to make their screening appointment too. And this type of communication can easily be extended to other areas of adherence.

Availability bias is another cognitive bias which could be used to try to improve adherence. Availability bias encourages us to believe that something that we can recall easily or which is more vivid or salient is more likely to happen. We identify with and are inspired by patients' own stories so enabling an exchange of stories could help to bring to life the benefits of adherence. Online patient forums help patients to gain access to success stories amongst others suffering from the same condition. Hearing a story of how someone who followed the prescribed programme of medication has been cured can inspire us to believe the same could be true for us if we do likewise.

Availability bias can also be used to influence people by creating a vivid picture or story of the long term consequences of not following a medical programme and can help to prompt and remind them of the likely future they face if they do not adhere to it. This tool has been used to good effect to encourage smokers to give up by showing them gruesome images of the lungs of a long term heavy smoker.

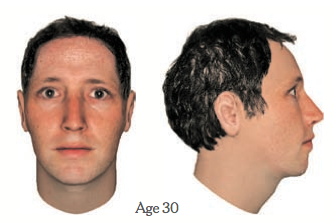

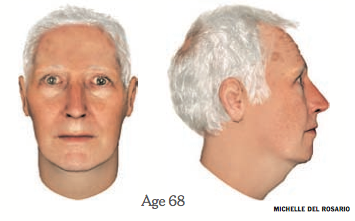

A significant reason for non-adherence is that people discount the future and value today and all it contains more than they do a distant future. We are often poor at imagining how we might be in the future and can almost compartmentalise our separate selves: the 'now' me and the 'future' me. (This is particularly true in the case of dieting; our 'now' selves are more than happy to leave dieting to the me of next Monday for example.) To tackle this problem, we might try harder to enable patients to imagine their future selves. A study from the financial sector by Professors Daniel Goldstein and Hal Erner-Hershfield (and others) conducted fascinating work on imagining your future self in order to improve retirement saving contribution rates. They demonstrated how participants who were shown realistic computer generated images of their future older selves, had a higher propensity to save for their retirement (see image). Those shown an image of their aged self invested 30-40% more money into a retirement savings account than participants who viewed an image of their current self. Making our older self more salient, more of a realistic concept, is an idea that could also potentially be used in a non-adherence context - creating a vivid image of what life might be like in the future if medication is not taken, in order to spur less compliant patients into action. As well as making the future more vivid, this technique could also utilise our fear and dislike of loss by making the potential decline in health and quality of life more salient and front of mind. The Behavioural Architects have looked at how this can be used in the context of eyecare, to prompt regular checkups as we get older, but the idea can also be extended to broader healthcare adherence.

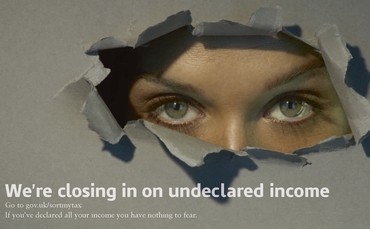

We can also encourage people to take medication by making them feel as if they are being watched. Research has shown that our behaviour changes when we think or feel we are being watched by others. It has also demonstrated that this feeling of being watched can be simulated simply by using pictures of eyes which prime us and remind us of what we should really be doing. For example, one study showed that contributions to a staffroom honesty box to pay for coffee increased by nearly three times over when pictures of eyes were included on the price list.[11] The same researchers have also found equally compelling evidence to show that eye posters in a canteen greatly improved rates of table clearing by canteen users and recently, how eye posters can deter bike theft. Recently, HMRC have used eye priming to invoke fear and encourage tax payments (see image below). Perhaps this technique could be used to good effect to increase adherence. If we were to feel that our doctor was keeping an eye on us, we might be more compelled to take our prescription meds, not wanting to disappoint such an authoritative figure. Maybe a personalised poster on the back of a patient’s bathroom door asking ‘Have you taken your medication today’ including an image of your doctor’s eyes or a daily email or text message showing the same thing could have a significant impact?

Conclusion

We have explored how behavioural economics is actually a multi-fold tool in analysing and tackling a challenge such as medical adherence. Not only can it provide us with a framework with which to analyse the issue and understand some of the triggers and barriers to achieving the desired behaviour (in this case taking a regular prescription drug), it can also show us how we might tackle that problem using a toolkit of concepts and approaches identified by behavioural science and its applications. It's early days but there is huge potential for behavioural economics to help change behaviour, simply, cheaply, and incredibly effectively.

[1] Glowcap testimonial http://vimeo.com/36808703

[2] Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes, RB “Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review” Arch Intern Med. 2007 Mar 26; 167(6):540-50.

[3] New England Health Institute, 2009 http://www.nehi.net/news/press_releases/110/nehi_research_shows_patient_medication_nonadherence_costs_health_care_system_290_billion_annually

[4] http://www.vitality.net/products.html

[5] http://www.vitality.net/glowcaps_testimonials.html

[6] Volpp, Loewenstein et al ‘A test of financial incentives to improve warfarin adherence’ BMC Health Serv Res. 2008; 8: 272.

[7] ideas42: Using Nudges to Improve Health: Sticking to Statins http://www.ideas42.org/using-behavioral-nudges-to-improve-disease-management/

[8] Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes, RB “Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review” Arch Intern Med. 2007 Mar 26; 167(6):540-50.

[9] Duhigg, C., ''The Power of Habit', Random House, 2012

[10] Jo's Cervical Cancer Trust

[11] Bateson, M., Nettle, D.,Roberts, G., ‘Cues of being watched enhance cooperation in a real-world setting’, 2006, Biology Letters, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0509, and Ernest-Jones, M., Nettle, D., Bateson, M. ‘Effects of eye images on everyday co-operative behavior: a field experiment, Evolution and Human Behavior 32 (2011) 172–178