In the last couple of decades the ‘strange wilderness of the subconscious mind’ detailed in Vance Packard’s seminal work ‘The Hidden Persuaders’ has become much better understood by social psychologists and behavioural scientists. Since it was published, back in 1957, marketers and researchers have learnt a lot more about the ways in which our brains function and about the many different subconscious influences which can affect our behaviour.

In this three-part series, we will look at some of the latest understanding around a particular area of subconscious influence - that of the incredible power of priming: how tiny cues and stimuli around us can subconsciously (and significantly) affect our behaviour. Specifically, we will explore the latest understanding and thinking around:

-

The hidden priming power of words and numbers: Words were some of the first cues discovered to prime our behaviour. More recently, social scientists have also found evidence that even the sound associations of particular words can prime our response. And numbers too can have priming effects.

-

The hidden potential of sensory priming: We can also be primed through our senses - by what we see, smell, hear, taste and even feel in our environment.

-

How simple physical actions can prime what we do, think and feel: We will look at how our own physical behaviour and actions and those of others can prime our subsequent thinking, judgement and behaviour.

Exactly what is priming?

Priming is when our brains make unconscious connections to our memory so that “exposure to a prime increases the accessibility of information already existing in the memory”. More specifically, social psychologists John Bargh and Julie Huang define the term thus:

"'Priming' refers to the passive, subtle and unobtrusive activation of relevant mental representations by external, environmental stimuli, such that people are not and do not become aware of the influence exerted by those stimuli."

Any type of stimuli in our environment - an image, sound, word, smell, taste and even physical movement for which someone has an existing strong association - may ‘prime’ us and affect our responsiveness to something, our judgement, and even our actions and motivations.

Take this sentence: “Ann went to the bank.”

What comes to mind will depend on whether the association for bank is related to a bank for money or a river bank. Has the reader been primed with associations related to rivers and water, or money and finance? What meaning is at the forefront of the mind?

Similarly, when we see ‘SO_P’, we may either think of soap or soup, depending on whether the concepts of eating or washing are at the forefront of our mind.

Generally speaking, stimuli prime our whole being, affecting our thinking and behaviour in countless dimensions. There are (at least) four different areas where priming has an impact, each of which have been measured, tested and classified by researchers. Priming can:

-

Make

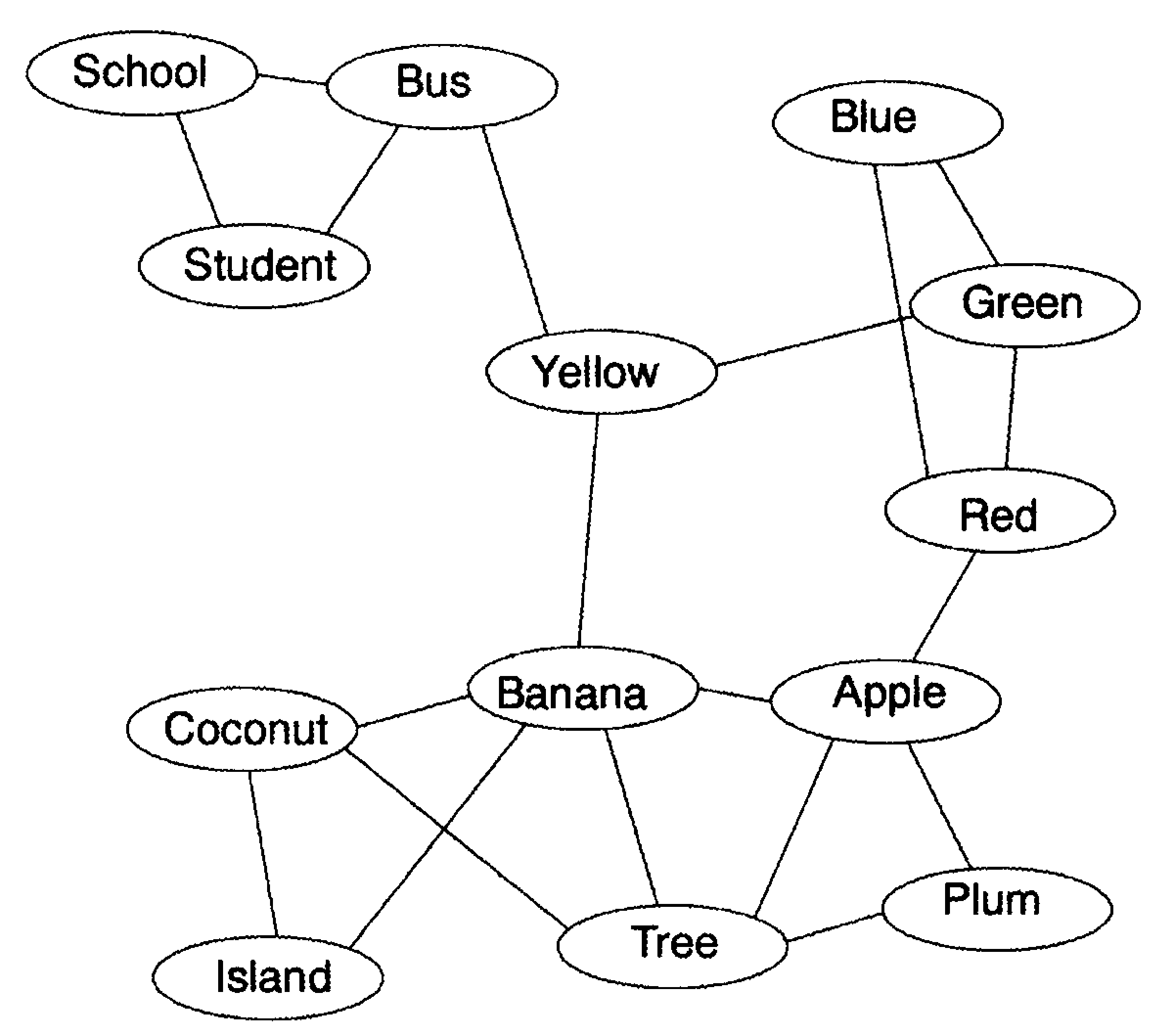

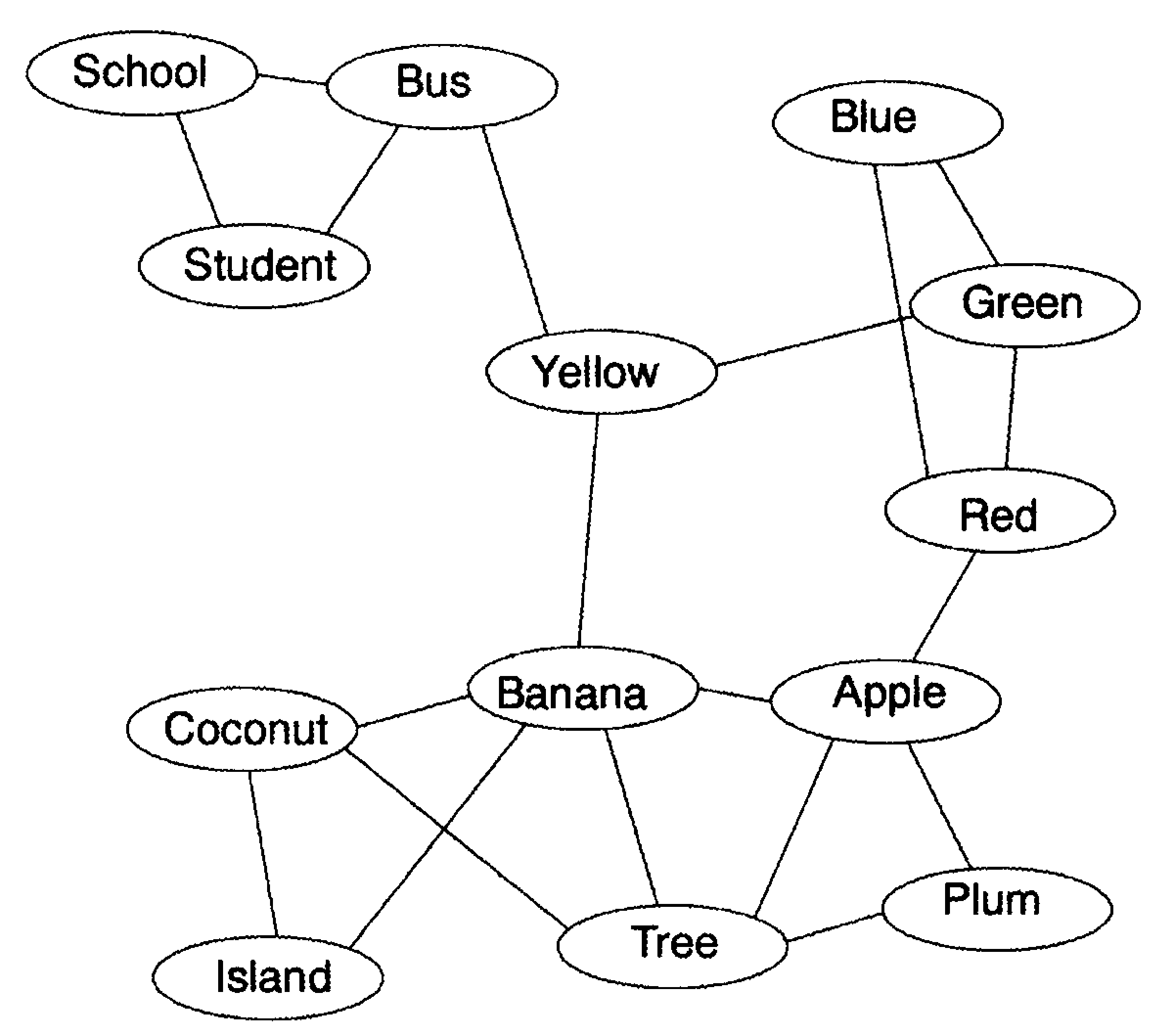

us faster to recognise or identify something: A simple example is where someone who has previously seen the word ‘yellow’ will be slightly faster to recognise the word ‘banana’ in a later context. (See image below.) This happens because the words ‘yellow’ and ‘banana’ are closely associated in memory. This is known as semantic or conceptual priming.

us faster to recognise or identify something: A simple example is where someone who has previously seen the word ‘yellow’ will be slightly faster to recognise the word ‘banana’ in a later context. (See image below.) This happens because the words ‘yellow’ and ‘banana’ are closely associated in memory. This is known as semantic or conceptual priming.

-

Affect our perception or judgment: For example, someone who has been primed with the concept of fear might judge something or someone as more threatening in a later situation. And whatever the situation they find themselves in after being primed, any question which involves them making a judgment such as “What is that?” or “Who is that?” is likely to be subconsciously influenced by the concept with which they have been primed. This is known as construal priming.

-

Affect our later actions or behaviour: For example, people first primed by reading words associated with impolite behaviour are subsequently more likely to behave rudely, interrupting another's conversation for instance. So, once again, any question which involves them taking action or making a decision about doing something is likely to be affected by what they have previously been primed by. This is known as behavioural priming. So we might think about how we could prime a person’s behaviour so they are more receptive to a particular brand, and to be more psychologically disposed or receptive to a brand’s tangible and intangible assets.

-

Affect our goals and motivations to do something: For example, someone primed with the concept of competitiveness may be more likely to want to behave more competitively in a later activity. Once again, in any subsequent situation in which someone asks themselves “What do I want to do? What am I motivated to do?” they will be influenced by what they have been primed by in an earlier context. This is known as goal priming. So we might think about priming the context so primed goals are in line with a brand’s assets.

We are not as capable of free thinking as we believe ourselves to be…

We are not as capable of free thinking as we believe ourselves to be…

Priming effects are considered outside of our control. Because they arise in our ‘System 1’ - the automatic, intuitive part of the brain - we have no conscious access to them, so people often wrongly attribute the real underlying reasons for their behaviour.

In fact people can be completely unaware that their behaviour has been changed or managed in any way. We tend to believe that we are rational and that everything we do in our daily lives is governed by our conscious choices. As social psychologists Chris Loersch and Keith Payne explain:

“People ordinarily feel that their judgements, behaviours and motives are freely chosen, reflecting personal concerns and preferences. […] Thus priming effects … emerge under conditions that allow people to misattribute the primed information to their own thought, feelings, or impulses.”

So it can be very bewildering for some – especially those of us who pride ourselves on our ability not to follow the herd or to act only after thoughtful deliberation of the pros and cons - to discover that we are not as free-willed as we thought and are just as susceptible to priming at a subconscious level as the next person.

Interestingly, priming effects can take time to wear off. Studies have found the effects of priming can last for anything from 15-20 minutes to a week, with a constant impact.

How does priming occur?

Neural imaging has allowed scientists to examine how these kinds of unconscious cues are processed in different regions of the brain and how these link to corresponding behaviour. For example, the midbrain regions which are known to respond to direct physical warmth, like that generated through holding a hot drink, are

the same regions which respond to social warmth – friendliness and generosity. Similarly, the brain regions activated when we touch something rough are the same ones to light up when we are having a hard time interacting with someone else. Roughness tends to be metaphorically associated with difficulty and harshness. So when some poor person is being given a rough time by Jeremy Paxman on Newsnight the same area of their brain will light up as when that person scrubs their nails with a brush.

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman says an effective prime needs to be strong enough to impact behaviour, but not so strong that it enters conscious thought – the effect must remain subconscious. When we consider this, it’s easy to see how this can happen in many occasions during our day, but it might be something that is harder to test in a lab.

Priming in relation to brand values and brand associations [mental and physical].

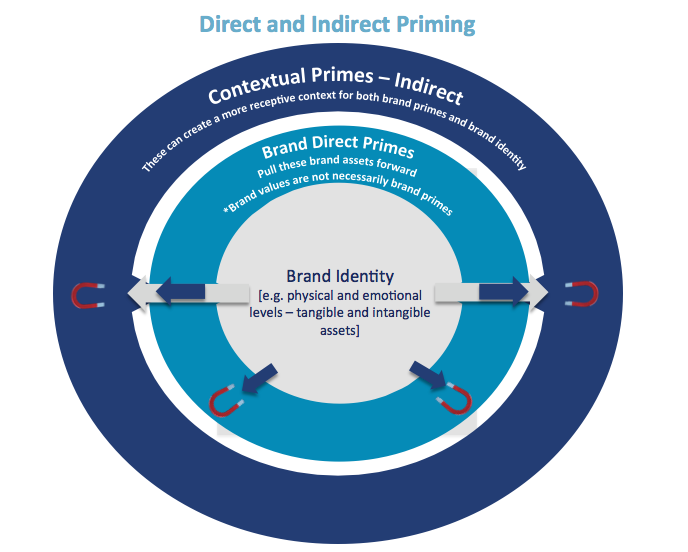

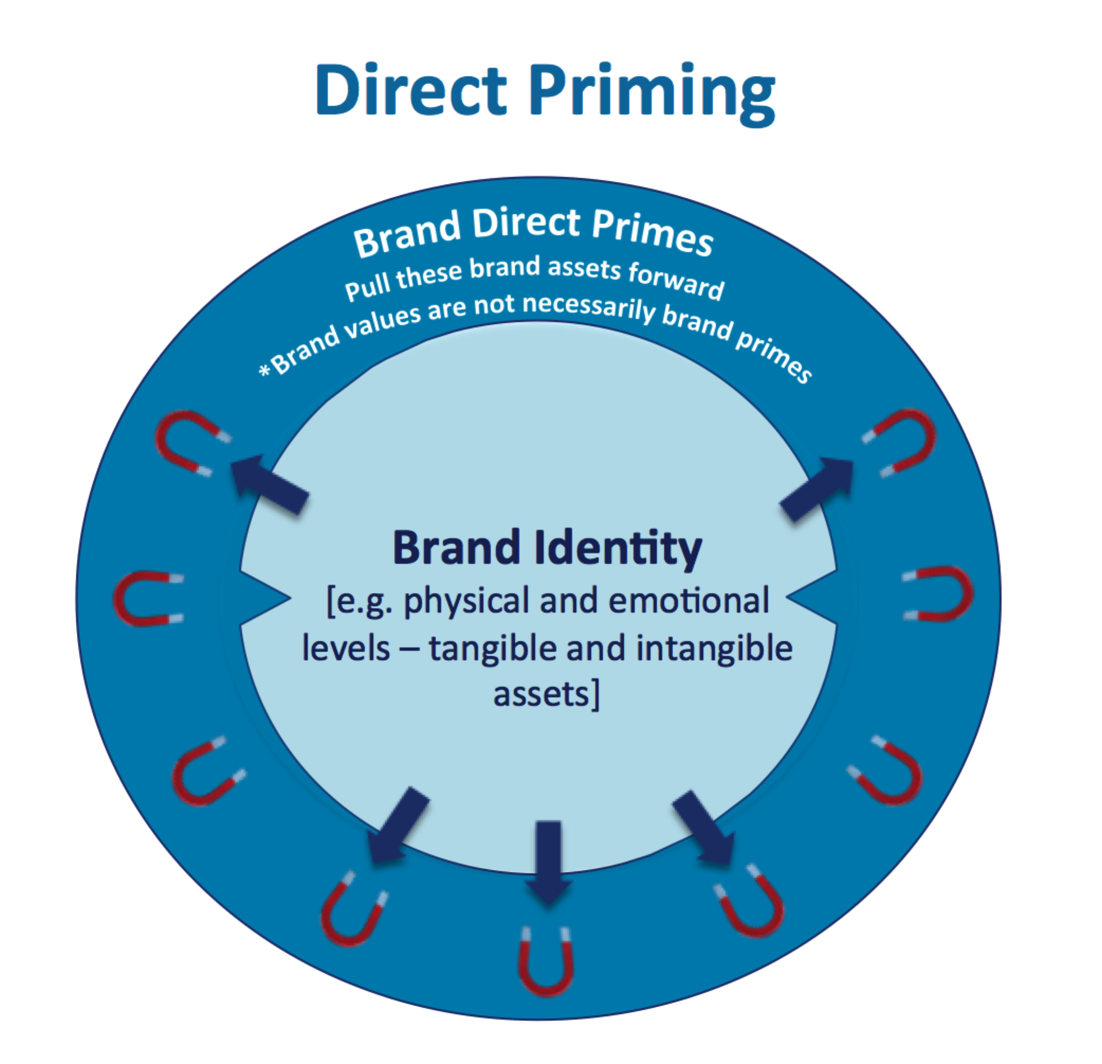

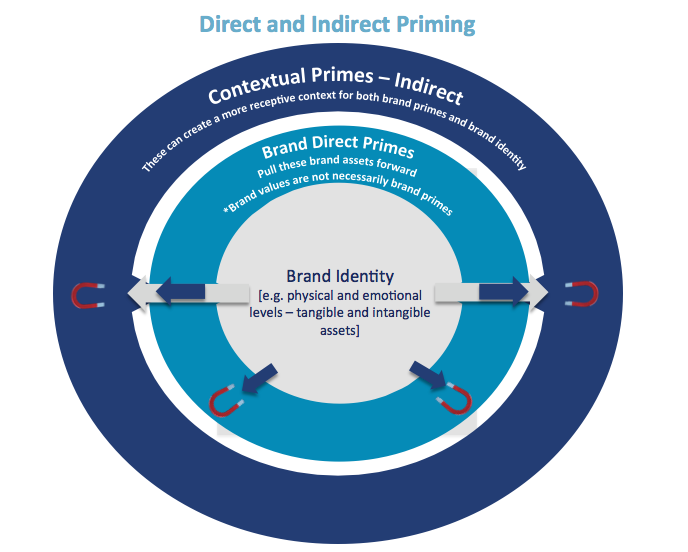

One of our main interests in priming is its potential subconscious impact on everything we think and do. This may be directly, by priming a particular behaviour or goal via certain stimuli, or by priming our thinking, our perceptions and judgements which could then also lead to an associated behaviour. We can conceptualise primes as having the ability to directly and indirectly create behavioural energy.

Priming can shape what we actually want people to do and so goes beyond the traditional brand focus around identity or values. Brand identity can often be static, or descriptive, and is often interpreted, whereas priming can have a clear and active impact on behaviour. Thus behavioural primes are not necessarily the same as brand values. Primes are things that should be actively stated [applied] rather than interpreted.

Primes can also have a much more indirect nature; such as that achieved by painting baby faces on the shutters of shops in an area of high anti-social behaviour and which results in a significant reduction of anti-social incidents, or postural priming, such as tasting a whisky in an armchair.

Brands tend to know their attributes, their values and associations - the tangible and intangible brand assets – and these are short cuts to a lot of information, but these are not necessarily the words, senses or physical behaviours that create the most subconscious energy and connection.

Direct brand priming

As we know, brands are a collection of tangible physical assets and intangible emotional ones. Critically, a brand needs to have a deep understanding of not only what these conscious and subconscious brand associations are [often in brand wheels or described as tangible and intangible brand assets], but also what the primes are that allow people to connect to brands more easily. With proper consideration and application of priming, a brand can further leverage or multiply its existing mental and physical associations, activating or bringing certain associations forward in the memory, making us more receptive to that association - it can prime the ‘behavioural pump’.

In years of working with Brand Models/Onions/Pyramids we have seen some quite imprecise language develop (which has taken a long time to develop!) that can be very subjectively interpreted. That’s why the right brand primes, whether words, senses or physical behaviour, need protection in the same way as brand identity – brands should experiment to demonstrate and determine their strongest primes and then jealously protect them!

Primes can help the magnetism of brands - the force of connection – provide more behavioural energy around brand connections.

A brand should know the primes that work for it, from words, to the senses and physical behaviours

Indirect brand priming

When thinking directly about what primes a brand’s subconscious connections, we tend to make the assumption that a person is in a particular emotional disposition or need state or in a particular context. If a consumer is in this state or context they are potentially already leaning towards our brand. However, we can also think more deeply about priming this actual emotional state or actual context so that people will be more disposed and more receptive to a brand’s subconscious associations – we will call this indirect brand priming – creating a disposition for active brand engagement [‘more enhanced or greater brand engagement’] - giving your brand a contextual head start.

Many of these insights around priming tie into the latest thinking about brand marketing from organisations such as the Ehrenberg Bass Institute. Primes can be seen as shortcuts or energy lines to both a brand’s physical recognition and mental associations. For big brands which often exist in a repertoire of acceptable brands, these mental shortcuts are critical for constant recruitment of your users beyond just subcategory association.

Deeper understanding of priming allows us to think about how to use priming in a more structured way as marketers and as researchers.

Priming part 1

The hidden priming power of words and numbers

HOW IS A PRIMING EXPERIMENT CONDUCTED?

Researchers tend to investigate priming effects using short, lab-based controlled experiments, recruiting students to participate in the study for a small monetary incentive.

A typical priming experiment is a two-step procedure:

-

an initial priming task, followed by:

-

a seemingly unrelated task to test the effect of the prime.

A participant in a study will be asked to complete a task, examples of which are outlined below, which will prime them with a particular concept. When they have completed that task, they are then asked to perform a second, unrelated task, in which researchers will measure how much the participant’s thinking and behaviour has been affected by the concept which has been primed. When priming using words, common techniques include:

-

Asking participants to unscramble a series of sentences which contain words related to the concept being primed such as kindness or hostility.

-

Asking participants to create words from strings of letters; for instance the letter string s-k-i-n-s-e-d-n makes the word kindness.

-

Word searches are sometimes used, with participants finding words which prime the particular concept.

-

Other techniques might be simply to ask a participant to read a paragraph which primes a particular concept eg a short passage about someone being hostile at a dinner party to prime hostility and unfriendliness.

Let's consider six areas where researchers have tested the effects of word-based priming stimuli, each of which shows just how far reaching are the effects of priming with words and numbers on our thinking, judgement and behaviour:

-

Cooperation and politeness

-

Selfishness and greed

-

Spending behaviour

-

Healthy living

-

Identity

-

Numbers

1) Priming cooperation and politeness

It’s often in our best interests to contribute to a common cause / public good, for example, making sure we invest in reducing air pollution or pay our TV licence fee. Recent research has shown how we can be primed to be more responsive to causes such as these or to collaborate more actively for the common good.

A study by Michalis Drouvelis, Robert Metcalfe and Nattavudh Powdthavee found significant effects from priming participants with words related to the concept of cooperation. Participants were primed with words such as teamwork, united, collective, collaborate, trust and share in a word-search. All participants (those primed and those in the control segment) were subsequently (in an apparently unrelated task) invited to contribute to a charitable cause from a fund of monetary tokens they had been allocated at the outset.

Those who had been primed with words relating to cooperation contributed significantly more generously. Only 37% of primed participants contributed no tokens, compared to 45% of the control group who had been primed with neutral words. On average those primed to be cooperative gave nearly seven tokens to the cause compared to only five tokens in the control group. And 13% of the cooperatively primed donated all 20 of their tokens.

One of the most well-known studies illustrating how our behaviour can be primed in this way was carried out by psychologist John Bargh and colleagues. Participants were primed to behave either politely or rudely by being given a word scramble task using either words associated with politeness – such as respect, courteous, graciously - or words associated with rudeness - such as bold, interrupt, disturb, obnoxious. There was also a control group primed with neutral words.

Participants were then asked to go to another room in order to take part in another, ostensibly unrelated task, which another experimenter would explain to them. On arrival, they found the experimenter deep in conversation with someone else. Unknown to them, they were timed over the course of 10 minutes to see how long it would take before they interrupted that conversation.

Those who had been primed with words associated with rudeness were far quicker to interrupt; waiting on average 3 minutes less than those primed with polite words. The 'rude' group interrupted after 5.5 min approximately, while the 'polite' primed group behaved much better, interrupting only after approximately 8.5 minutes of thoughtful standing around. Over 60% of the rudely primed participants interrupted compared to less than 20% of the politely primed.

-

What state of mind does a consumer need to be in to be most receptive to a particular brand and how might we stimulate this state?

-

How might we prime respondents in research to be more cooperative and collaborative?

-

How might we prime people in general to be more generous and trusting?

-

Think about the forced social situations such as commuting where priming politeness or consideration to others could make our commute a little less stressful.

2) Priming selfishness and greed

A study by Kathleen Vohs and her collaborators looked at the impact of priming people with the concept of money and found, generally speaking, that it made them more selfish and greedy (perhaps it really is the root of all evil). Priming people with a word scrambling task related to an abundance of money e.g. “high a salary desk paying” made people more self-sufficient, less likely to ask for assistance, and less helpful towards others. Participants were also less inclined to donate money to a charitable cause.

3) Priming spending behaviour

Words can also prime us to think differently when evaluating a potential purchase and can even affect our likelihood of buying.

Primed by credit cards: We might think that all consumers evaluate products in similar ways, weighing up the costs and benefits equally. However, a recent study by Promothesh Chatterjee and Randall Roseshowed how priming with words relating to different payment mechanisms influenced consumers’ evaluations of a product. Students were asked to do a word scramble task which either:

-

primed the concept of credit cards eg “TV shall watch we Visa”, or

-

the concept of cash eg "TV shall we watch ATM"

In each case, they had to make a sentence from four out of the five words. There was also a control condition primed with neutral words.

In four separate studies, Chatterjee and Rose found a number of effects which showed how priming with words related to credit cards can subconsciously make us think more of the benefits of a product as opposed to the costs:

1) The students in the credit card prime group made more recall errors of the costs of a camera than those in the cash prime group. They were shown a picture of a camera and then a list of three benefits or product attributes (eg zoom, high resolution, megapixels) and three cost features (eg warranty price, RRP and cost of additional battery recharge kit).

2) A second study found that participants primed with credit cards tended to identify slightly more words related to the benefits of a product than the costs – in this case the product was a netbook.

3) A third study found that those primed with credit cards responded faster to the benefits of an iPhone than those primed with cash. They were also prepared to pay more for the phone ($205) than the cash prime group ($163).

4) A fourth study asked participants to choose an MP3 player – either an expensive ipod with many features and benefits, or a ‘Zune’ which was much cheaper, but had fewer features and benefits. 76% of those in the credit card prime group chose the more expensive ipod. In contrast only 25% of the cash prime group chose the ipod; the majority opting for the Zune MP3 player.

The researchers believe that each prime - credit or cash - directed attention to the different features of a product. Randall Rose comments:

"When [consumers are] exposed to new products and thinking about paying with credit, they tend to focus on the good things about the product - the aesthetics of it, the features that are better than other products they're considering, the sexiness and luxury of it… That's as opposed to details related to cost, like the price, shipping cost, warranty cost, installation cost and effort."

-

Priming a credit card concept tended to subconsciously direct consumers’ attention more to the benefits of the potential purchase in their evaluation. The researchers speculate that this is because credit cards tend to make payment and the actual exchange of money less salient and vivid and, therefore, less painful since there is no physical loss - your card is returned at the end of the transaction. And it could impact on spending - consumers are more likely to purchase a product and spend more on it or opt for the more expensive model.

-

Priming a cash concept on the other hand, directed consumers’ attention towards the cost of the purchase. Cash payments are more tightly coupled with the exchange of money and are more salient and vivid since the consumer physically parts with cash - there is the pain of actually handing over money, drawing on the concept of loss aversion. Likewise, this effect would impact on spending, making consumers either less likely to buy a product at all, or more likely to opt for a cheaper model.

-

How might we prime consumers to think more about the benefits or drawbacks of a potential purchase or action?

-

How might priming techniques be used in consumer research, for example, innovation projects? How would you prime research respondents with words to focus on either the benefits or costs of a product they are testing via a credit card or cash prime?

We can also be primed to think less about spending and costs, by being primed instead to think more about the experience a product gives us. A study by researchers at the University of Stamford tested how priming with the word ‘time’ affected evaluation of and attitudes towards participants' iPods.

Participants were first asked “How much time have you spent on your iPod?” or “How much money have you spent on your iPod?”, priming either the concept of time or money. In the next task they were asked “When considering your iPod, what thoughts come to your mind?”. Those previously primed with the word ‘time’ valued their iPods more highly and had more positive attitudes towards the device than those primed with money.

The researchers believe that priming with time prompts people to think about the personal connection they have with a service or product, and their experience with it. They recommend that “to actively foster feelings of connection, brands should draw consumers’ attention to their time spent and thus the experiences gained with the brand.”. This also links to research by Michael Norton and Elizabeth Dunn which suggests that buying experiences rather than material goods leads people to feel happier.

-

How can we prompt consumers to think more about their experience with a product or brand?

-

Or get them thinking more about the context in which brands are used and the values associated with this context?

-

We should be more aware of the increasing value of consumers’ time; we should think about both the time spent by a consumer with our brand e.g. when consuming [how we might apply a value to this time] as well as the time we ask of consumers with our brand communications. This could change how we frame or position brands, promotions and research engagements.

4) Priming for healthy living

Primed to take the stairs: Priming can also affect how active we are. In a study by psychologists John Wryobeck and Yiwei Chen, asking participants to make a sentence out of scrambled words such as fit, lean, active, athletic ie priming the concept of being active - made them significantly more likely to use the stairs instead of the lifts to attend a second, unrelated study. Almost all of those so primed took the stairs up one floor to reach their next destination – a full 22 out of 24 participants, whereas only 14 out of the 24 participants in the control group took the stairs.

Priming our eating behaviour. Esther Papies, a social psychologist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands has looked at the impact of priming on the behaviour of dieters. Previous research has found that subliminal exposure to words such as “pizza, chocolate, tasty” or reading sentences such as “Bill is having a big piece of apple pie” led dieters to begin thinking about hedonic eating and made them less likely to stick with their diet.

Priming dieters to eat less: Papies then directed her attention to testing the effect of a healthier prime – that of priming dieting. At a local butcher’s shop, she placed a poster on the glass entrance door advertising a weekly recipe that was “good for a slim figure” and low in calories. In the control condition there was no poster on the door. As customers queued inside the shop, a tempting smell of grilled chicken wafted from a big grill oven and customers were allowed to help themselves to free samples of bite-size meatball snacks as they queued. On leaving the shop, customers were asked to complete a short questionnaire which included question

s about how restrained an eater they were and whether they often dieted (chronic dieters).

In the control condition chronic dieters ate more than non-dieters, perhaps unable to resist the delicious smell and the free bite-size meatballs. In the poster primed group though, the chronic dieters ate fewer snacks than dieters in the control condition where there was no poster. So simply priming the concept of low calorie food made them less likely to snack.

PRIME YOURSELF TO DIET

-

Understanding the effectiveness of priming is sometimes easier if you start closer to home.

-

Is there a way you can prime yourself to eat more healthily? What tiny stimuli could you place in your home and workplace to subconsciously affect your behaviour?

-

Esther Papies believes it’s possible to help yourself to diet and eat less by priming yourself with certain words. She says some of the best words to focus on are slim, healthy, fit and weight. If you’re feeling tempted to eat, prime yourself with fat-fighting vocab. “Put them in your calendar so you see them before you head for lunch,” Papies says. Or you could stick the words on the fridge door to prime you in the kitchen.

5) Priming identity – “Who am I?”

Although each of us is one person, we may actually have multiple identities, although only one or two may be salient in our mind at any point in time. So someone can be a managing director, a mother, a daughter, and a musician - identities which all have importance at different times of the day, week, month and year. Being able to prime a particular identity can be useful to increase responsiveness or generate behaviour change.

Primed to be more individualistic: It wouldn't be particularly useful, and it would certainly make for a very dull world, if everyone was of one opinion and behaved in the same way in every set of circumstances. Differences between colleagues, for example, when a combination of diverse viewpoints and ideas come into play, can often result in better, more effective solutions. Anne Mulchay, chairman and former CEO of Xerox believes:

“You need internal critics - people who have the courage to give you feedback. This requires a certain comfort with confrontation, so it’s a skill that has to be developed. The decisions that come out of allowing people to have different views are often harder to implement than what comes out of consensus decision-making, but they’re also better.”

Word priming can predispose a person to a particular identity, displaying certain characteristics, for example, to be more individual or more conformist. Experiments have shown that priming people with words such as ‘individuality’, ‘solo’, ‘differ’ or ‘myself’ using a scrambled sentence task can remind people of their independence and make them less likely to conform to others’ views in any subsequent task. And asking people to read a short text or short story written in the first person e.g. containing words like ‘I’ and ‘mine’, or even to write a passage in the first person can help to heighten the individual's sense of identity and sense of self, and to encourage the idea of being freer from the influence of others.

Primed to be more of a team player: Likewise, people can be successfully primed to be more collectivist, keep in mind the social context and think more of others with words such as ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘cohesive’, ‘ours’ and ‘agreeable’. For example, one study found that priming this concept helps to open our minds to other ideas. Participants primed in this way tended to be able to list more possible arguments in a debate and were more likely to listen more to another’s point of view. Another study found that participants were more likely to take on another’s perspective.

Priming has also demonstrated its power to affect our behaviour negatively, for instance by priming certain stereotypes:

Primed to feel and act old: One of the most well-known studies illustrating how our behaviour can be primed was carried out by psychologist John Bargh and colleagues. It showed how students who had been subconsciously primed by words linked to an elderly stereotype - such as Florida, lonely, grey, bingo, forgetful, wrinkle, knits, ancient and traditional - each of them stereotypically older behavioural attributes - subsequently walked more slowly down the corridor as they were leaving the lab, a distance of about 10m. This priming effect was totally subconscious. None of the students reported being aware of the prime.

(Avoiding) priming gender stereotypes: We can also prime the saliency of real identities using words. For example, a study on gender priming showed how female students at a liberal arts school in the US performed worse in a spatial awareness test when reminded of their gender in a short questionnaire. When reminded of their quality education at a private college, the gender effect disappeared and girls performed much better. Similar results have been found for ethnicity effects.

-

This has very powerful and simple implications for marketing and research. People have multiple identities so we may want to think about which identity we want to prime, draw to the front of mind and make more salient when conducting research?

-

Similarly, at what times as researchers is it useful to prime individuality? And at what times would priming cohesiveness and conformity be more relevant?

-

In marketing, what mental state or identity would make someone more receptive to a brand’s subconscious connections and how could we prime this?

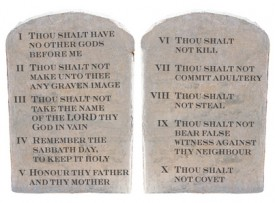

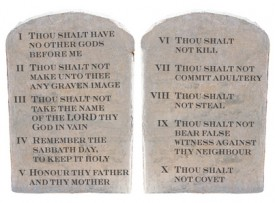

Priming a moral identity: It’s also possible to prime moral identity and influence levels of honesty. Dan Ariely has illustrated how a simple way to do this is to ask people to recall and write down something like the Ten Commandments or an honour code before completing a task.

In one experiment he and his colleagues asked participants to write down as many of the Ten Commandments as they could remember, or a list of ten books they had read at school. They were then asked to work out the answers to twenty number matrices, at the end of which they had to report how many they had answered correctly. For each correct solution, they were to be given $10. Participants cheated less and were more honest about the number of matrices they had got right when they had been primed by writing down the Ten Commandments.

Ariely also leverages these primes in his online course on irrationality, requiring students to read an honesty clause and consciously opt-in to agreeing to obey the rules, and reminding students for each and every quiz that they should not cheat.

6) Priming by numbers

One of the most important findings in priming research has been how numbers can have subconscious effects on our later judgement and decisions. Numerous studies have demonstrated the impact that seeing, reading and using numbers in one context has on our decision-making and perceptions in a later context. We

subconsciously anchor to numbers, using them as reference points even though we are unaware we are doing so.

Priming what we might be willing to pay: For example, one study by Dan Ariely, George Loewenstein and Drazen Prelec demonstrated how we subconsciously anchor to a random number. Students were first asked to write down the last two digits of their social security number eg 89. Next they were asked if they would be happy to bid this amount in dollars (eg $89) on a range of different products. Then they actually bid on these products in an auction.

Incredibly, those with high ending social security numbers made higher bids than those with low ending numbers - showing the power of subconscious anchoring. For example, those with high social security card digits bid $56 on average for a cordless keyboard compared to just $16 bid by those with the lowest digits. These were totally subconscious effects: when asked, people did not feel they had been influenced in any way by their social security number.

Priming what we pay for a meal: Other studies have found similar effects. A number in a restaurant name affected how much people were willing to pay in one experiment. Students were presented with a sheet containing pictures of two upscale restaurants and asked to circle the name of the restaurant they chose to assess. This action was intended to draw the participants’ attention to the name. The first restaurant was called ‘Restaurant Mon Jardin’, the second either ‘Studio17’ or ‘Studio97’. After circling the name, they were then asked to estimate how much they would pay for a meal at that restaurant. Those who had evaluated Studio17 restaurant were willing to pay over $24, yet those who had evaluated Studio97 were willing to pay nearly $33. Again, a random number affected willingness to pay.

These types of number primed subconscious influences can affect all sorts of situations, from experienced estate agents assessing the value of a home - who’ve also been shown a listing price, assessments of the performance of a rugby player when exposed to the number on the player’s rugby shirt, to the subconscious effects of minimum payment values in credit card bills which can pull down the amount people choose to repay each month.

Priming debt repayments: In the latter study looking at credit card repayments, Professor Neil Stewart of Warwick University found that people who were given no minimum repayment figure paid off more of their debt than people who were shown their bill with this figure, demonstrating how people use the minimum payment as a reference point for any larger repayment they choose to make. Over 400 volunteers were given mock credit card bills for £435.76. Half were given a suggested minimum payment and the average repayment made was just £99 on average (23% of the balance). The other half - who were not given any required minimum payment - paid an average of £175 - 40% of the balance. Without a minimum payment to anchor to, people paid more back.

Professor Stewart highlights the negative impact of this prime: “These results should be of real concern to credit card companies. Virtually all credit card statements include minimum payments. But this consumer safeguard has an unexpected negative consequence: Minimum payments distort the behaviour of many customers in a way that increases interest charges and increases the duration of their debt. Those paying off the balance in full each month seem to be immune, but anyone repaying only part of the debt is at risk―not just those making only the minimum payment.".

Stewart thinks credit card companies need to illustrate better what different possible repayments will cost customers in the long term – perhaps using a table of repayment scenarios - to make people less susceptible to these anchoring effects. We also tend to anchor to extremes and then pick the middle option(s) so a table which presented three or four repayment options and which included the minimum and a full repayment as the extremes could result in higher repayment values.

-

Could we think harder about the numbers people see on packs, in store, online, on letters and emails and how these might impact on their behaviour?

-

What numbers might consumers be primed by in contexts we have control over?

Conclusion:

In this part one of our series we can see how words and numbers can be used to prime us in numerous ways. From increasing speed of recognition, to impacting on perception or judgement or subsequent behaviour, to affecting our very goals and motivations. We have also presented a model to think about priming in relation to brands where we have differentiated between direct and in direct brand priming.

From a marketing and market research perspective this deeper understanding means we need to think about priming in a structured way in order to maximise the opportunities. We need to be aware of both direct and indirect priming.

Thinking strategically and executionally about what primes we want to use to increase the direct and indirect magnetism of our brands can have significant impact. We need to think how we can not only prime direct connection to a brand but also indirectly, by making a person more receptive to a brand’s existing subconscious connections and dispositions.

In consumer research we need to think more about how we use priming, for example by invoking the right mental state in respondents or being aware of or carefully designing the context a respondent is in, but we also need to be aware of (and aim to avoid) priming by accident.

“Companies have much to gain from recognising the role and nature of the unconscious mind in consumer behaviour.”

Philip Graves ‘Consumerology’

“Potential primes are all around…inadvertent priming is [often] an inevitable consequence of almost every market research process.”

Philip Graves ‘Consumerology’

us faster to recognise or identify something: A simple example is where someone who has previously seen the word ‘yellow’ will be slightly faster to recognise the word ‘banana’ in a later context. (See image below.) This happens because the words ‘yellow’ and ‘banana’ are closely associated in memory. This is known as semantic or conceptual priming.

us faster to recognise or identify something: A simple example is where someone who has previously seen the word ‘yellow’ will be slightly faster to recognise the word ‘banana’ in a later context. (See image below.) This happens because the words ‘yellow’ and ‘banana’ are closely associated in memory. This is known as semantic or conceptual priming.  We are not as capable of free thinking as we believe ourselves to be…

We are not as capable of free thinking as we believe ourselves to be… the same regions which respond to social warmth – friendliness and generosity. Similarly, the brain regions activated when we touch something rough are the same ones to light up when we are having a hard time interacting with someone else. Roughness tends to be metaphorically associated with difficulty and harshness. So when some poor person is being given a rough time by Jeremy Paxman on Newsnight the same area of their brain will light up as when that person scrubs their nails with a brush.

the same regions which respond to social warmth – friendliness and generosity. Similarly, the brain regions activated when we touch something rough are the same ones to light up when we are having a hard time interacting with someone else. Roughness tends to be metaphorically associated with difficulty and harshness. So when some poor person is being given a rough time by Jeremy Paxman on Newsnight the same area of their brain will light up as when that person scrubs their nails with a brush.

subconsciously anchor to numbers, using them as reference points even though we are unaware we are doing so.

subconsciously anchor to numbers, using them as reference points even though we are unaware we are doing so.