In the 18th century 216,000 people worked in the mines.

Many were women and children, some only five or six years old.

Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper was a reformer.

He believed children should have some education.

It wasn’t so much that children shouldn’t work.

It was that they should also be allowed time for study.

That meant studying The Bible, amongst other things, but certainly The Bible.

So Lord Ashley tried to introduce a bill limiting children’s working hours underground to 10 hours a day.

But this was defeated, and the limit was set at 12 hours.

In 1838, there was a disaster at a pit in Silkstone, near Barnsley.

A thunderstorm caused a river to overflow its banks.

The river flooded the pit.

And in the pit, 26 children died: eleven girls aged between 8 and 16, and fifteen boys aged between 9 and 12.

The scale of the tragedy caused a flurry of media interest.

Lord Ashley used it to expose conditions in the pits.

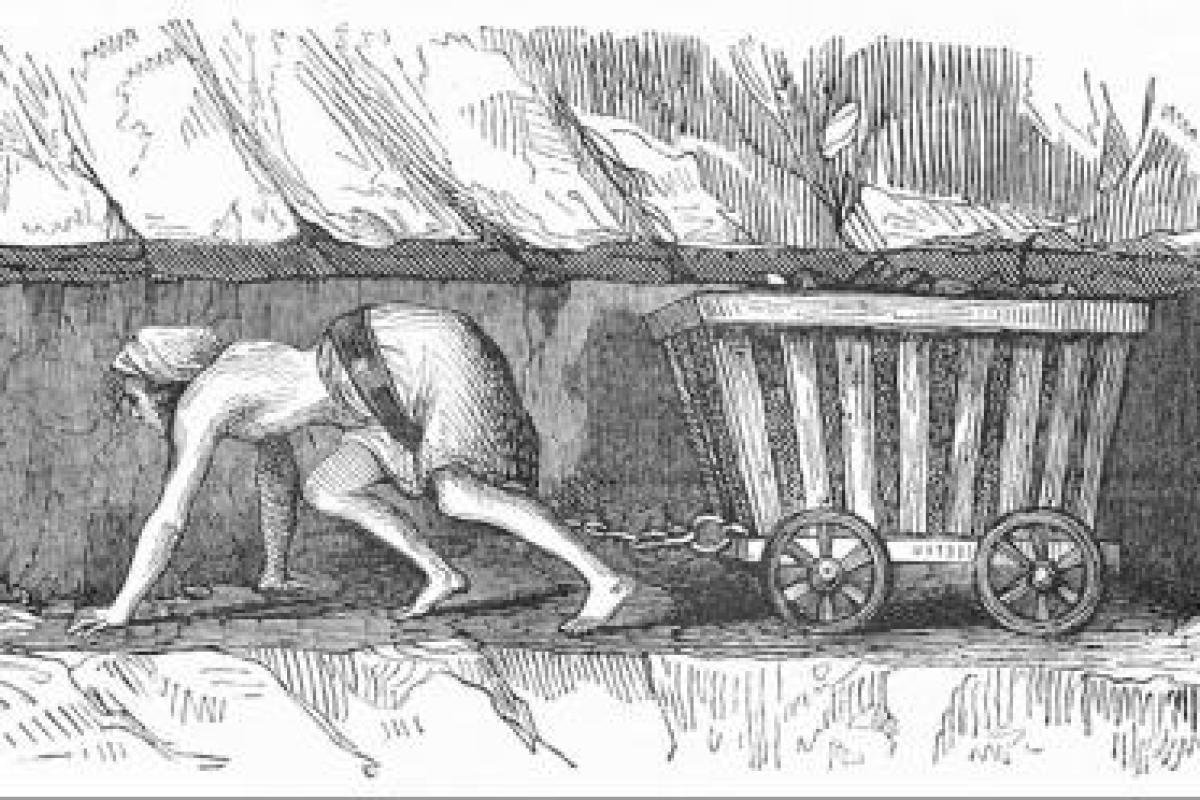

He revealed to the papers that boys and girls were preferred because in some places the pits were only two feet high.

Roughly up to the average person’s knee.

The children were used for pulling the coal carts.

They had chains fastened round their waists and passed between their legs as they crawled along on all fours.

But, bad as this was, it wasn’t seen as quite horrifying enough for a Victorian audience: the poor were expected to have rough lives.

So Lord Ashley revealed, from interviews, that most of the children had no education at all.

Meaning they had “never heard of Heaven or hell”, or “never heard of God or Jesus”, or “never heard of The Bible”.

For a Victorian audience this was indeed shocking.

But most shocking of all – he revealed to the newspapers that women worked alongside men and, due to the heat, were stripped naked to the waist.

Revealing their breasts.

And even more unbelievably, the men mining coal alongside women and children often wore nothing but their hats.

Their male organs on full display.

The shock of Victorian England was so great that reforms even greater than the working hours were quickly carried through.

Women and children were banned from working in the mines at all.

It wasn’t death that Victorians found unthinkable.

It was disgusting, naked bodies.

The very sight made girls “unsuitable for marriage and unfit to be mothers”.

The lesson to be learned is that in order to get what we desire from our audience we must find what’s important to them.

Not just what we think should be important.

However serious we think child deaths are, that’s not what got the law passed.

However trivial we think nakedness is, that’s exactly what got the law passed.

Before we start to speak we must find out what our audience needs to hear.

Then we must talk to them in their language.

Otherwise we’re just talking to ourselves.