‘Yes, it is a rich language… full of the mythologies of fantasy and hope and self-deception — a syntax opulent with tomorrows. It is our response to mud cabins and a diet of potatoes; our only method of replying to … inevitabilities.’

There’s an excellent production of Brian Friel’s 1980 play ‘Translations’ running at the National Theatre in London (until 11 August).

The drama is set in 1833 amongst the Irish-speaking community of Baile Beag, Donegal. Bibulous Hugh, ‘a large man, with residual dignity’, teaches Latin and Greek literature to the local peasantry at his informal ‘hedge-school.’ In a ramshackle old barn his students learn grammar and word derivations, and swap quotations from Homer, Tacitus and Virgil.

‘There was an ancient city which, ‘tis said, Juno loved above all the lands. And it was the goddess’s aim and cherished hope that here should be the capital of all nations – should the fates perchance allow that.’

English is rarely spoken in the area ‘and then usually for the purposes of commerce, a use to which [that] tongue seemed particularly suited.’

Meanwhile British troops are camped nearby charting a map of the area for the Ordnance Survey. This entails Anglicising the local place names. So Bun na hAbhann becomes Burnfoot; Druim Dubh becomes Dromduff; and Baile Beag becomes Ballybeg.

Hugh is no admirer of the English language. ‘English succeeds in making it sound…plebeian.’

And he explains to the British sappers that their culture is lost on the Irish.

‘Wordsworth? … No, I’m afraid we’re not familiar with your literature, Lieutenant. We feel closer to the warm Mediterranean. We tend to overlook your island.’

The British are also in the process of establishing a national education system in Ireland. This is one of the first state-run, standardised systems of primary education in the world. English will be the official language, and the new system will make the traditional Irish-speaking ‘hedge schools’ redundant.

The drama prompts us to think about control. The British claim that their measurements and mapping will lead to fairer, more accurate taxation. But there’s an underlying suspicion that darker motives are at play. On the face of it the new school system will be superior to the old, and some in the Irish community regard English as a gateway tongue to travel and better prospects. But Hugh is concerned that Ireland is losing its cultural identity.

‘Remember that words are signals, counters. They are not immortal. And it can happen — to use an image you’ll understand — it can happen that a civilization can be imprisoned in a linguistic contour which no longer matches the landscape of … fact.’

We may recognise some of these themes in the world of commerce. Periodically our leaders, our owners and our Clients seek to monitor our output and ways of working; to map the landscape and contours of the business. We embrace timesheets and targets; scales and scorecards; ratios and rotas. Of course, it’s all in the interests of efficiency and best practice. ‘What gets measured gets done’ and so forth.

But there’s often a misgiving that measurement is a means of re-ordering priorities, of setting a new agenda, of enacting control; and a concern that the measures can become an end in themselves. As Sir John Banham, the former President of the CBI once observed:

‘In business we value most highly that which we can measure most precisely… Consequently we often invest huge amounts in being precisely wrong rather than seeking to be approximately right.’

Similarly we may find that our leaders, owners and Clients seek to impose their own language upon us. We are taught catchphrases and buzzwords; axioms and aphorisms; jargon and generalisation. Listen and repeat. Listen and repeat. As we endeavour to wise up, we dumb down. As our ambition expands, our vocabulary shrinks.

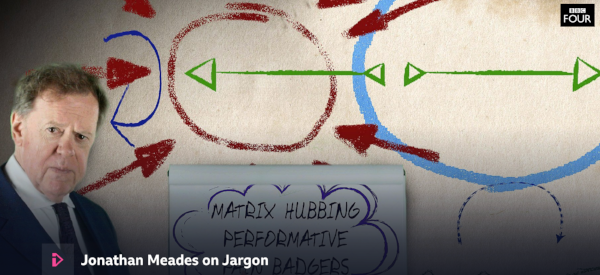

In his recent documentary ‘On Jargon’ (BBC4, 27 May), the brilliant writer and film-maker Jonathan Meades contrasted jargon with slang.

‘Jargon is everything that slang is not. Centrifugal, evasive, drably euphemistic, unthreatening, conformist. ...

Whilst slang belongs to the gutter, jargon belongs to the executive estate.

It is the clumsy, graceless, inelegant, aesthetically bereft expression of houses with three garages; of business people who instinctively refer to their workmates as colleagues…It is delusional. It inflates pomposity, officiousness and self-importance rather than punctures them.

Slang mocks. Jargon crawls on its belly - giving great feedback, hoping for promotion.’

Now I should concede that I have been no stranger to aphorisms.

When I was in leadership positions, I was prone to headlining new agendas; to punching out big themes. And I have often referred to my workmates as colleagues.

Of course, it is the responsibility of leaders in modern businesses to achieve corporate clarity and coherence. But it is imperative in so doing, to avoid clichéd conventional wisdom; ‘newspeak’ and ‘doublethink.’ And it is critical that independent thought and freedom of expression are not victims of the process.

Sometimes, in seeking to control difference, we simply succeed in making everyone the same.

One of the last of the great Calvalier Clients was Geoffrey Probert, who ran the deodorant and oral categories at Unilever. He was mindful that Agencies were at great pains to fit in with their Clients; to conform to their language and way of working. He warned against it.

‘Agencies can spend too much time trying to be like their clients. We’ve got loads of people just like us. We need you to be different. That’s the point. Just concentrate on doing the things we can’t do.’

This article was originally posted on Jim Carroll's Blog