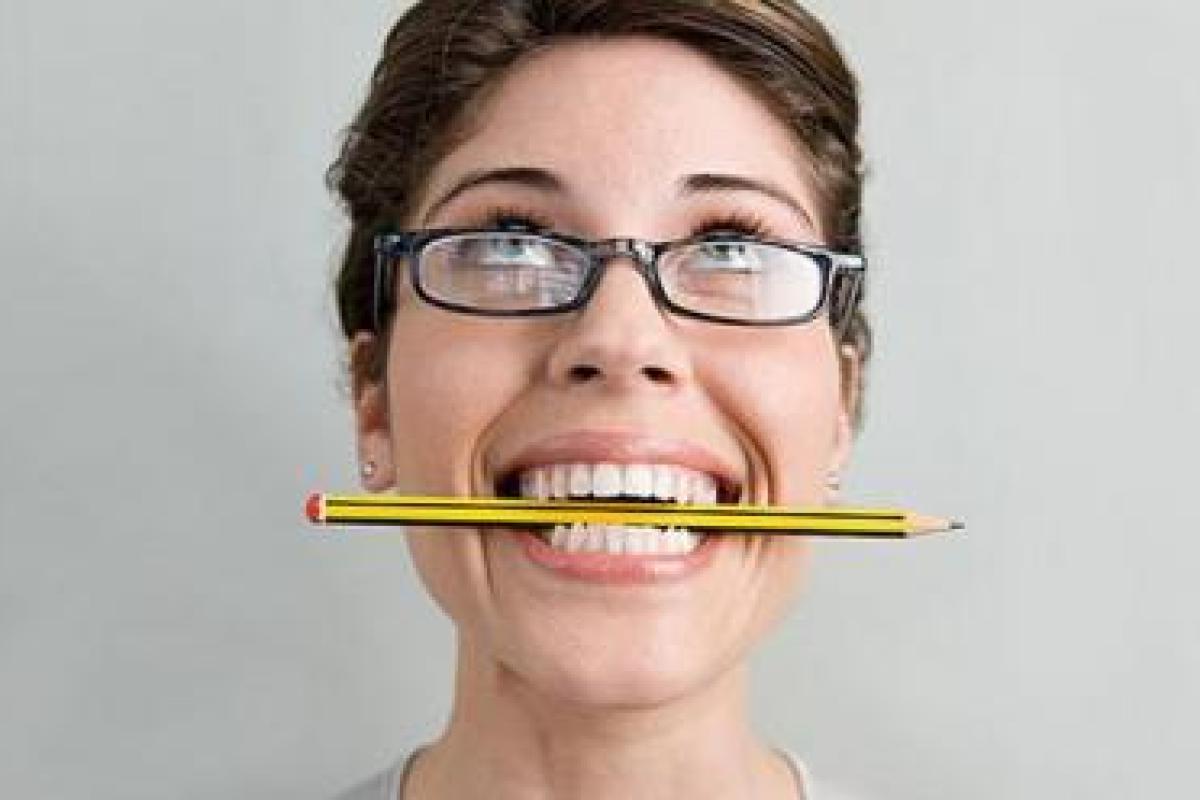

Before you get stuck into this article find a pen and place it between your teeth horizontally, whilst nodding your head up and down… just like in the image here. Are you done?

This article is the third in a three-part series in which we explore how we can be primed or influenced subconsciously by tiny cues and stimuli all around us. Our previous two articles looked at how we can be primed and influenced by words and numbers, and by our five senses.

In this final piece we explore how our physical behaviour – how we stand or sit, how we walk or talk – can subconsciously impact on our thinking and perceptions and may not only have the potential to improve the performance and thinking of our teams and ourselves in the workplace and but could even work to strengthen a brand or improve output in research. Specifically, we look at seven different areas:

- Primed by a smile, a frown or a nod

- Power posing

- Primed by the technology we use

- Primed to think and act younger

- Priming Top Gun vision

- Primed by what we wear

- Priming creative thinking in a break

Brands tend to know their attributes, their values and associations - the tangible and intangible brand assets – and these are short cuts to a lot of information, but are not necessarily the words, senses or, as we will focus on in this article, the physical behaviours that can create subconscious energy and connection.

Primed by a smile, a frown or a nod

Primed by a smile, a frown or a nod

Simple actions and behaviours like putting a pen between our teeth can actually shape how we feel, how we perceive things and how we go on to behave later. It activates the same facial muscles activated when we smile. And smiling itself puts us in a better mood. Daniel Kahneman points out that “Being amused tends to make you smile and smiling tends to make you feel amused.” So putting a pen in your mouth horizontally can force you to form a smile expression and, even though your smile has been forced, as a consequence, you will feel happier. Conversely, holding the pencil between your lips, so that it shoots directly forwards making a pursed lip, frowning expression will make you feel more miserable.

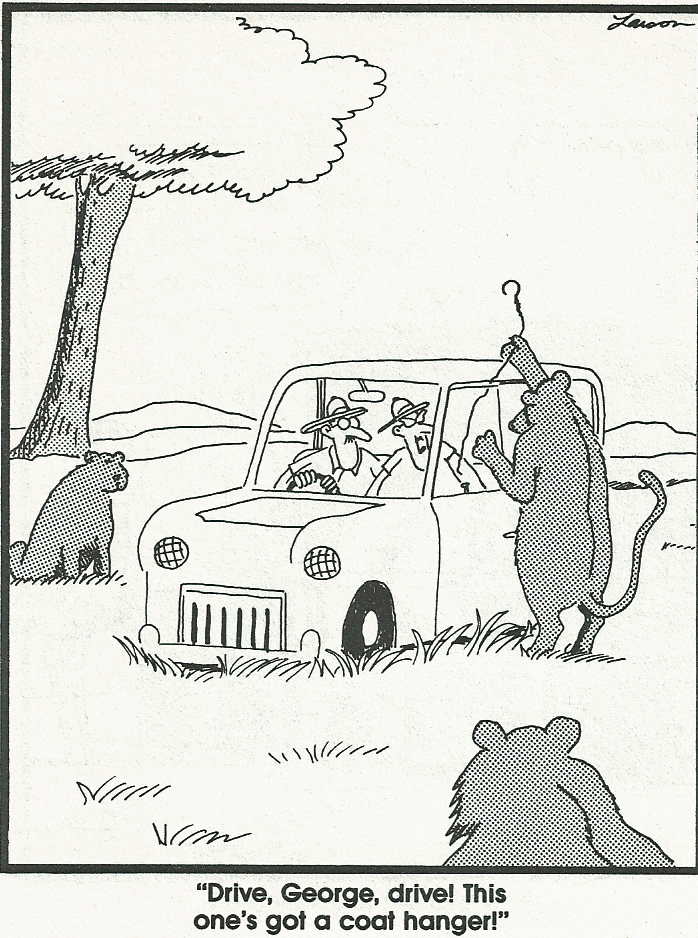

These tiny gestures have been shown to have an impact on how funny or sad we find something. In one study, students who were asked to rate the humour of cartoons from The Far Side while holding a pen in their teeth found the cartoons funnier than those who were made to frown by holding it between pursed lips or those who had simply held the pen in their hand.

The teeth group rated the four cartoons 5.14 out of a potential 9 whereas the pursed lip group and the hand group rated the cartoons at only 4.32 and 4.77 on average. Although the effect was quite small, it was consistent for each of the four cartoons.

When you nod your head, you may also be influencing yourself in ways of which you are unaware. In another experiment, students were recruited to listen through headphones to an audio recording of radio editorials, with the apparent aim of testing the performance of the headphones. Half were told to listen whilst nodding their head up and down and the other half were told to shake their head from side to side. The audio recording contained a few songs and also a discussion about raising college tuition fees. After the exercise, students were asked “What do you feel would be an appropriate dollar amount for undergraduate full-time tuition per year?". Those who had nodded in the listening exercise, seemingly gesturing ‘yes’, tended to accept the proposal to increase college tuition fees that they heard through the headphones and be more willing to pay high tuition fees on average. Those who had shaken their heads tended to reject the proposal preferring that tuition fees were reduced. And those who were not asked to shake their head in any direction during the listening exercise opted to keep tuition fees unchanged. This specific result is likely to be more relevant in western cultures such as the US where the study was conducted. In India for example, people shake or bob their heads in far more subtle ways to indicate positivity or negativity.

Think how these simple behavioural insights might change our day to day lives, or our interaction with others:

What mood-influencing gestures could a brand prime to make people more receptive to the physical and mental associations of a brand?

How might we prime a good mood? Research has shown that when we are in a good mood and happy we are more likely to go with the status quo/rely on our System 1.

Brands could own some physical pose or ritual that creates the right subconscious prime - think about the Churchill Insurance nodding dog and the line ‘Oh Yes’.

In research, could we think harder about creating a positive (or negative) mood before beginning any research task? Or whether it would be useful to ensure people are likely to be more – or less - sure of their opinions by getting them to nod or shake their head a little? Both these approaches could be interesting disruption techniques to develop a stronger understanding.

From a marketing perspective, the concept can also help us to think about positive reciprocity – there are many ways we can make someone smile – maybe conceptualise this as the starting point vs. end point, in that it can create a more receptive person for other messages we want to deliver.

Power posing

We may also be able to affect our thoughts, decisions and behaviour by the way we stand and present ourselves. Our body position and stance can affect how confident we feel, as well as communicating our level of confidence to others.

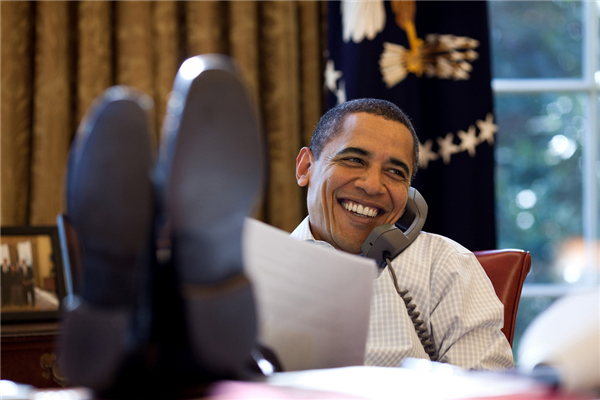

Amy Cuddy, a professor at Harvard Business School, studies types of nonverbal behaviour and has conducted some fascinating research on what she has termed ‘power posing’. She points out we often naturally express power by opening up – taking up more physical space e.g. stretching, standing taller, leaning back, putting our hands behind our heads, legs stretched out and so on - any physical movement in fact that makes us take up more space and look bigger. Primates and humans both do this to express dominance and power - just look at the triumphant pose of any winning athlete at the end of a race.

professor at Harvard Business School, studies types of nonverbal behaviour and has conducted some fascinating research on what she has termed ‘power posing’. She points out we often naturally express power by opening up – taking up more physical space e.g. stretching, standing taller, leaning back, putting our hands behind our heads, legs stretched out and so on - any physical movement in fact that makes us take up more space and look bigger. Primates and humans both do this to express dominance and power - just look at the triumphant pose of any winning athlete at the end of a race.

professor at Harvard Business School, studies types of nonverbal behaviour and has conducted some fascinating research on what she has termed ‘power posing’. She points out we often naturally express power by opening up – taking up more physical space e.g. stretching, standing taller, leaning back, putting our hands behind our heads, legs stretched out and so on - any physical movement in fact that makes us take up more space and look bigger. Primates and humans both do this to express dominance and power - just look at the triumphant pose of any winning athlete at the end of a race.

professor at Harvard Business School, studies types of nonverbal behaviour and has conducted some fascinating research on what she has termed ‘power posing’. She points out we often naturally express power by opening up – taking up more physical space e.g. stretching, standing taller, leaning back, putting our hands behind our heads, legs stretched out and so on - any physical movement in fact that makes us take up more space and look bigger. Primates and humans both do this to express dominance and power - just look at the triumphant pose of any winning athlete at the end of a race.

The New Zealand All Blacks' pre match Hakka ritual is another example of this. It not only works to intimidate the opposing team but also, importantly, may serve a purpose for the All Blacks themselves, allowing them to prime feelings of dominance and power in themselves.

There's one particular kind of power posing which many men practise regularly. It's called manspreading and they do it on the subway to claim and then dominate their space. Unknown to them, it should also set them up for a powerful day. In the US a campaign launched by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority is set to deter offenders. But perhaps women should give it a go? Apart from the power priming potential, there's a limit to how long anyone should have to put up with this...

Cuddy notes that not only does “Your body language shape who you are” but also that “Your body can shape the mind”.

Her studies suggest that simply assuming different poses automatically releases different hormones into the body. Try this out if you need a bit of a power boost: lie back in your chair, put your hands behind your head and your feet on the table. After a few minutes this will trigger a release of testosterone into the bloodstream. Whenever you need to take on an alpha role, assuming this pose will cause your body to produce more testosterone and you will feel more confident. Testosterone is found in dominant behaviour - it increases before and after a competition, but drops after a crushing defeat (such as a trading loss). So after things go wrong, or if you feel defeated by something or someone, assume a power pose and feel better.

Her studies suggest that simply assuming different poses automatically releases different hormones into the body. Try this out if you need a bit of a power boost: lie back in your chair, put your hands behind your head and your feet on the table. After a few minutes this will trigger a release of testosterone into the bloodstream. Whenever you need to take on an alpha role, assuming this pose will cause your body to produce more testosterone and you will feel more confident. Testosterone is found in dominant behaviour - it increases before and after a competition, but drops after a crushing defeat (such as a trading loss). So after things go wrong, or if you feel defeated by something or someone, assume a power pose and feel better.

The opposite of the power pose is caused by the release of cortisol which is a stress hormone. It is released if you adopt a non-threatening, unconfident posture such as drooped shoulders, hands in your lap, touching your neck or standing with your shoulders hunched and your arms folded. Cortisol is found in people who tend to be more anxious and stressed - often those with low social status. High cortisol levels are linked to poor health eg memory loss, hypertension and impaired immune problems.

Cuddy and her colleagues analysed the impact of these poses on changes in specific endocrine levels and found that high-power poses decreased cortisol by about 25% and increased testosterone by about 19% for both men and women. In contrast, low-power poses increased cortisol by about 17% and decreased testosterone by about 10%.

They went on to test the effect of high and low power poses on candidates attending a job interview. Candidates were asked to pose in private for a couple of minutes beforehand: half in a high power pose and half in a low power pose. The result?

The interviewers wanted to hire all the people who had been in the high power pose! Those who had adopted a low power pose prior to their interview scored 3.8 out of 7 for performance and 2.0 out of a potential 3.0 for hireability. However, those who had adopted a high power pose prior to their interview scored 4.6 for performance and an average of 2.4 for hireability. High power poses led to an improvement in performance of 12 percentage points and an improvement in hireability of 14 percentage points. Rather disconcertingly other apparently more relevant qualities like experience and qualifications had no influence on the hiring decision. Cuddy and her team comment that "high-power posers appeared to better maintain their composure, to project more confidence, and to present more captivating and enthusiastic speeches, which led to higher overall performance evaluations.".

This is a very new area of research, however, and it’s not yet quite clear what the mechanisms are that help to create this effect. A new study published in 2015 by Eva Ranehill and her colleagues put the impacts of power posing into question. She believes “more research is needed to identify the precise conditions for such effects.” Although there is clearly still lots of work to be done, it is hard to believe something like the All Black’s Hakka would have no behavioural priming effects. It’s going to be an exciting few years as this field of research develops.

Thinking about indirect priming - what physical activities, stances and gestures could increase disposition and receptiveness towards a brand’s assets [both emotional and physical]?

We need to think deeply about how people physically interact with our brand and how we can use this understanding to prime subconscious connection to a brand’s assets / associations.

The above is also critical in terms of research. Think about the actual physical behaviour around consumption and how important this might be to gain a deeper understanding of consumer behaviour.

In the workplace, could teams develop a high power pose exercise or physical movement that could boost assertiveness or creativity - but please, not a company dance routine.

Should governments use these insights in policies such as ‘get back to work’ schemes which help to return the unemployed to work? The Behavioural Insights Team have already piloted a scheme which uses insights from behavioural science to get people back into work sooner. Could they also leverage priming within the scheme to give confidence to job applicants?

And in research, could we use physical gestures and poses to prime confidence or assertiveness when useful?

Primed by the technology we use

Cuddy has built on these findings in collaboration with Maarten Bos (also at Harvard Business School). In another study, they looked at the impact of different body postures in operating everyday technology - from smartphones and tablets, through to laptops and desktops. Just like a victory pose or putting your feet up on the table, using a desktop means we tend to adopt a more expansive body posture, whilst using a smartphone constricts our body posture, causing us to hunch our shoulders and tense our neck.

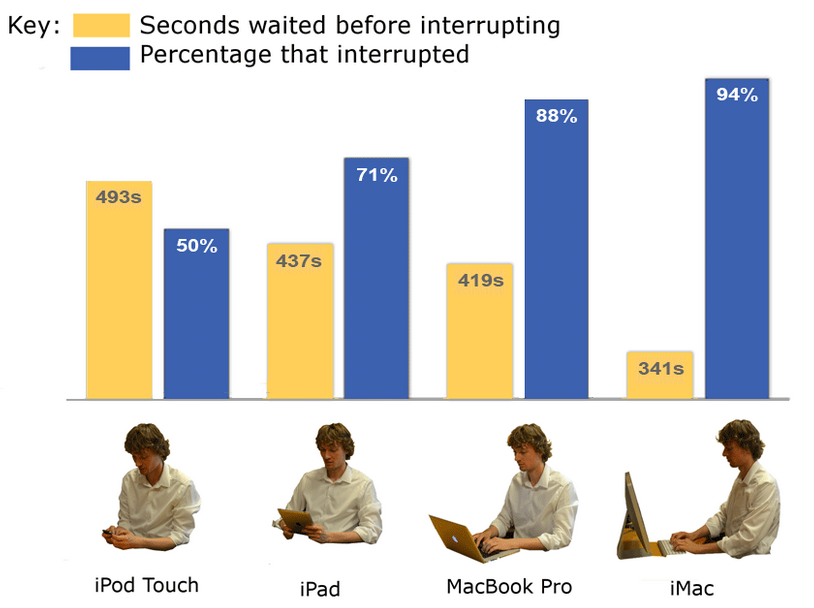

In their study entitled ‘iPosture’ they asked participants to complete a number of tasks and then wait for 5 minutes for the researcher to return. The researcher specifically told them “I will be back in five minutes to debrief you, and then pay you so that you can leave. If I am not here, please come get me at the front desk.”. They then deliberately delayed their return by up to 10 minutes. Some participants completed the tasks on an ipod Touch, others on a tablet, laptop or desktop. Cuddy and Bos found that more assertive behaviour - measured by whether participants sought out the researcher and came to the front desk - tended to be linked to the size of the electronic device used.

- Of the participants using a desktop computer, 94% took the initiative to fetch the researcher back, whilst of those using the smallest device, the iPod Touch, only 50% left the room.

- Of those who did leave the room, the size of the device appeared to affect the amount of time they waited. The bigger the device, the shorter the wait time. Desktop users waited around 5 and a half minutes before fetching the experimenter, for instance, while iPod Touch users waited over 8 minutes on average.

Bos sees the implications of this finding in our everyday lives: “People are always interacting with their smartphones before a meeting begins, thinking of it as an efficient way to manage their time. We may, however, lose sight of the impact the device itself has on our behaviour and as a result be less effective.”.

Bos and Cuddy are currently testing these findings in other contexts, such as how the posture in which we sleep impacts our behaviour and whether and how the device we use in the workplace impacts our assertiveness.

Do we need to be more aware of the potential impacts of using different devices on our behaviour - in our workplaces for example?

Research is increasingly conducted through smartphones due to greater ease and the fact that real-time responses can be so quickly obtained. Should we think harder about when and where we ask respondents to engage with us and just how their physical behaviour (triggered by use of their smartphone) might influence what they report?

Primed by what we wear

Two researchers - Adam Galinsky and Hajo Adam - have looked closely at how what we wear can prime us, something they call ‘enclothed cognition’. They conducted a series of experiments to see how clothing and what we associate with an item might affect our performance in a later task. In one experiment, those wearing a lab coat - an item of clothing often associated with attentiveness, carefulness and accuracy - did better in the well-known Stroop Test - a test which measures our ability to focus our attention on a tricky task.

In another experiment, participants were asked to put on identical white coats, but were either told it was a painter’s coat or a doctor’s coat. Next, they were asked to complete a ‘spot the difference’ task (see image for an example of one of the tasks), identifying as many differences as they could find between two pictures. Those who were wearing the 'doctor’s' coat noticed around 12 differences, whilst those wearing a 'painter's' coat noticed 9. Galinsky and Adam believe the effect is caused by the qualities we tend to associate with doctors – we believe they are careful, rigorous and good at paying attention – which are typically different to from the qualities we associate with the stereotype of a painter.

It’s interesting to see ways in which this type of priming might be strategically applied. For example, a new UK organisation called ‘Suited and Booted’ provides men’s suits – often designer label cast offs from the City – to vulnerable men looking to make a new start in life and who need to look smart when attending job interviews and seeking accommodation. While what we wear undoubtedly affects what others think of us, priming research shows that it works in another way too – by affecting our own behaviour. One of Suited and Booted’s clients commented “It’s about the decisions you can make about yourself if you feel confident. A good suit can give you that confidence…even if you’ve just come out of prison.”

In research, should we think more about what respondents wear during missions or tasks?

Respondents often attend depths or groups straight after work, and come in their working clothes be they official uniforms or just outfits worn for work. Where possible and applicable, should we encourage them to change and dress differently? Think about using changes of clothing to disrupt an existing habit or build new habits.

This stimulates lots of ideas such as should we dress in certain ways to prime different types of thinking or behaviour?

Should we make sure when working from home that we still dress for work?

How might a staff uniform or outfit prime not only customers but the staff themselves?

Priming creative thinking in a physical break

There may be other techniques to help us get the best out of ourselves in the workplace. Most of us recognise that taking a mental break from what we are doing can often boost our brains and help us come up with new ideas. But recent research, by Ken Gilhooly and his colleagues found that the type of break and what we do or think about in that break is important for boosting creativity.

In a series of experiments, they found that the effect of taking a break was strongest when the break was spent doing a task or activity which required different thinking skills from those needed for the first task. In the initial task, participants were asked to list potential uses for a brick. They were then given a short break where they were asked to carry out some different tasks. Those who worked on a spatial reasoning task in their break were subsequently able to think of 20% more uses for a brick than those who, in their break, had completed a task which was similar to the brick task.

This finding can be seen in working styles in both new and historical contexts. For example, Google is famous for its innovative working time policies. ‘20% time’ where Google staff are encouraged to spend a fifth of their time working on personal projects may help to prime creativity in the rest of their day - particularly if their chosen project calls on different skill sets from other tasks.

Looking further back in time, we might speculate that some of the greatest minds unknowingly primed their thinking and perceptions by how they went about their day. In her book "Daily Rituals: How Artists Work", Mason Currey illustrates how they may have primed their thinking to be at its most creative. She details 160 choreographers, comedians, composers, filmmakers, philosophers, playwrights, painters, poets, scientists, sculptors and writers, analysing the habits and rituals of the likes of Benjamin Franklin, Henri Matisse, Stephen King, Gustav Mahler, Ludwig van Beethoven, Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison. Many of the examples she describes show how they found ways to step away from their main task and turn their minds to something else, often seeing the spaces in between their work as crucial to their overall productivity and creativity. In fact, many of the greatest minds seemingly frittered away parts of their days, albeit within highly structured routines. Few worked particularly long hours on their primary work goal (eg writing a symphony) and most worked between 3 to 5 hours each day. Here are some of the ways they disengaged from their primary task:

- Patricia Highsmith used to relax by tending her snails

- Morton Feldman recommended, "After you write a little bit, stop and then copy it. Because while you're copying it, you're thinking about it, and it's giving you other ideas.".

- Igor Stravinsky did headstands.

- Ernest Hemingway defrosted the fridge.

When planning a new project or campaign, maybe it would be productive to start with a different task or to schedule in breaks during the course of a day’s work?

In research, should we embed a number of different missions demanding different thinking skills in between the key tasks we need respondents to engage with, to prime greater creativity or accuracy?

Think about distraction tasks to free your brain and use it differently.

Primed to think and act younger

Research by Cuddy and Bos has mainly looked at short time effects, across minutes and hours, rather than days and weeks. But other research has suggested that how we behave in our day to day lives in general can have much longer-term effects on our mind and body.

Cuddy recently tweeted: "A lot of people seem to use their age as a script for their lives. No need to do that, as far as I can tell.".

And she could be right. We sometimes use our age as an anchor or reference point for how we should behave when perhaps this might be damaging. If we pay attention to instructions to 'Act your age' or even 'Dress your age' might we be limiting our lives in some way? As we grow older many of us accept that we may not be as quick, strong or as nimble as we once were. Yet there is some optimistic sounding research that shows that if we behave, think and live as we did when we were younger, it can make us stronger and fitter as well as cognitively more able.

One of the most recognised studies in this area, the Counterclockwise study, was carried out in 1979 by award-winning psychologist Professor Ellen Langer. She used the full range of priming stimuli - words, sensory primes and behavioural primes. Langer placed her study participants in a specially designed, prime rich environment and then asked them to think, read, write and behave in certain ways, further strengthening the priming effect. She recruited two identical groups of frail, elderly men who took a battery of cognitive and physical tests and were then sent off on a week long holiday to a monastery in New Hampshire which was retro-fitted in the style of 1959.

The men were split into two groups and both asked to discuss recent topical issues such as the launch of the first US satellite Explorer 1, Castro’s advance in Havana and the results of the previous year’s NFL game. They listened to Perry Como and Nat King Cole and watched Some Like It Hot and Ben Hur. But each group did this in one of two ways:

- One group of men were told to talk in the present tense, and discuss topics current in that era - pretending they were young again and living in the 1950s. They were also asked to write a brief autobiography as though it were 1959 and bring in a photo of their younger self, both of which were distributed to all the other participants in the study. This helped to prime them in a number of ways – getting them to think, see, write, and behave in ways that brought to mind the 1950s.

- The other group were told to discuss topical issues of the 1950s, but in the past tense and reminisce about that era. They also wrote a short autobiography but written in the past tense and brought in photos of their current selves.

At the end of the week, Langer retested both groups physically and cognitively. While both groups showed cognitive and physical improvements, the men who had spent the week behaving as if they were actually back in 1959 made the most improvements. Their vision, hearing, memory and cognitive ability all improved - 63% of the first group performed better in intelligence tests and they even looked younger in photos. Most incredible of all was the improvement in their physical strength and ability. Their joints became more flexible, their arthritis diminished and they were able to straighten their fingers which previously they had been unable to do and their strength of grip improved.

Langer said "At the end of the study, I was playing football with these men, some of whom gave up their canes. It is not our physical state that limits us, it is our mindset about our own limits and our perceptions. Wherever you put the mind, the body will follow.".

Her study demonstrates how multi-sensory and behavioural priming using simple cues in the environment can affect our later behaviour and thinking.

Applying this insight to our lives and those of others could have an incredible impact. Perhaps hotels could offer retro holidays where visitors are transported back to an era from their youth?

The baby boomer generation approaching retirement with greater life expectancy has high expectations that they can and will remain healthy. Moreover, they are willing to spend and therefore represent a huge market. Euromonitor forecasts that the global spending power of those aged 60 and above will reach $15 trillion by 2020. With this in mind, there could well be a market for products and services aimed at keeping a younger mindset in order to stay healthy and young at heart.

This illustrates once again the importance of context on behaviour and perceptions in a research context. The location in which we research and how we prime respondents beforehand could make a difference to how they think and behave.

Priming Top Gun vision – a final eye opener!

Since her Counterclockwise study, Langer continued her research into which behaviours might impact on particular elements of our health. One finding was that making people feel like pilots improved their vision. Many people believe that you must have at least 20/20 vision to be a pilot. When participants in a study were asked to be Air Force pilots and don green army fatigues to fly a working flight simulator their vision improved in 40% of individuals compared to 0% in the control group.

Conclusion

So before you read the conclusion strike a pose! In this article we have shown how powerful physical behavioural priming can be. From a brand perspective it is certainly worth the effort to think how we might tap into this power. Perhaps we should think about how to combat the behavioural priming of technology which might reduce assertiveness or openness. We might also think how to build rituals into consumption or even into packaging so as to positively prime consumers. Think more about what behaviours or gestures might prime more receptive moods such as the armchair whisky moment [perfect postural priming].

In consumer research the power of this area is endless both from the perspective of energising respondents, to priming thinking and behaviour in distinct ways via uniforms or postures.

Every single element of our external environment is reflected and mirrored in our minds and consequently in our behaviours, and to a large degree, subconsciously. Priming shows that our minds and behaviours are more malleable than we might think. Knowing this means we have a new tool at our fingertips, a tool which can be fashioned in any way we wish. We simply need to apply it.

So think back to all three articles, put your feet up on the desk and your hands behind your head and think how you might strategically and executionally harness the subconscious power of priming.