This article is part two of a three-part series in which we explore how our thinking and behaviour can be subconsciously influenced or primed by tiny cues and stimuli around us. In part one we looked at how words and numbers can affect our behaviour in different ways. In part two, we look at how our behaviour can be primed by each of our five senses – what we see, smell, hear, taste and even feel in our environment and how this affects our thinking, judgements and behaviours.

Just as it is said that there is no neutral way to present choice, it is important for us to be aware that everything primes, and because everything primes, we need to be very deliberate about how and what we are priming. This article shows how different sensory primes lead to changes in perception and behaviour.

Before this deep dive into sensory priming we will briefly recap on what we defined in article one about how to think about priming in relation to brand values and brand associations [mental and physical].

How does priming relate to branding?

Priming can shape what we want people to do and so goes beyond the traditional focal points of branding regarding who people are or what a brand is. Brand identity can often be static, or descriptive and is often interpreted, whereas priming can have a clear and active impact on behaviour. So behavioural primes are not necessarily the same as brand values. Primes are things that should be actively stated [applied] rather than interpreted.

Brands tend to know their attributes, their values and associations - the tangible and intangible brand assets – and these are short cuts to a lot of information, but are not necessarily the words, senses or physical behaviours that create the most subconscious energy and connection.

The other important point, in relation to priming and brands, is that primes can have both a direct and indirect subconscious impact on everything we think and do. We could directly prime a particular behaviour or goal via certain stimuli, or we could prime someone’s psychological state, which could impact on their thinking, perceptions or judgements, and thus indirectly predispose them towards an associated behaviour.

Direct and indirect brand priming

Primes can help the magnetism of brands, the force of connection – providing more behavioural energy around brand connections. Either via:

- Direct priming - the primes that allow people to connect to brands more easily; or

- Indirect priming - priming a particular emotional state or a context so that people will be more disposed to or more receptive to a brand’s subconscious associations.

Deeper understanding of direct and indirect priming allows us to think about how to use priming in a more structured way as marketers and as researchers. [Please see article one for more detail on each area.]

SENSE 1: Sight – Open your eyes to visual priming

Priming good behaviour

Good behaviour - such as putting our litter in the bin rather than dropping it on the ground - is something we know to be morally correct and socially responsible. We also know that not behaving in a moral fashion could damage our reputation if people were to know about it, which in turn could damage our acceptance in society. Behavioural scientists call this concept - that of what we know we ought to be doing and our perception of whether our behaviour will be approved of by others - an injunctive social norm. But how to remind people they should behave well, particularly in situations where there is no-one watching?

A team of researchers at Newcastle University in the UK tested the effect of priming people with simple, salient images to simulate the feeling of being watched - without using technology or the presence of a real life person. Using an image of watching eyes on a poster they were able to increase the likelihood that people would behave honestly when it came to paying for drinks in an unmanned coffee room (see images on the left). We tend to notice faces, the eyes in particular as they stand out from other stimuli and get our attention. And the staring eyes remind us of times when we have actually been watched in previous experiences.

Here's what they did. They posted new price lists each week over a period of 10 weeks in their unmanned department coffee room, where people paid for their drinks by dropping money into an honesty box. Whilst the prices remained unchanged, each week there was a different picture at the top of the price list either of flowers or of a face with eyes looking directly at the observer (all the pictures measured 15×3cm).

In the weeks with eyes on the price list, staff paid on average 2.76 times as much for their drinks as in the weeks with flowers. “Frankly we were staggered by the size of the effect,” said Gilbert Roberts, one of the researchers involved in the study. The graph shows that while flowers have little impact on honesty, watching eyes (and the clearer, more penetrating and direct the gaze the better), have the greatest subconscious influence on our morality. Interestingly nobody commented on the eyes being there so we can assume the processing was mainly subconscious.

The same researchers have since found equally compelling evidence to show that eye posters in a canteen greatly improved rates of table clearing by canteen users. Using eye images next to signs asking canteen users to place their trays in the racks provided halved the number of people leaving table litter.

Similarly, posters with images of watching eyes together with the headline ‘Cycle Thieves: We are watching you’ placed next to university bike stands have cut thefts by 62% in those areas. This idea is now being tested to deter car thieves at various UK train stations by British Transport Police (BTP) as well as other UK police and government entities. It is far cheaper than installing CCTV – a few pounds for a poster versus thousands of pounds for the cameras. The UK’s HMRC have also adopted these techniques to encourage citizens to pay their taxes.

How might eye images be used in other contexts to prime more compliant behaviour or honesty?

How and in what other contexts can we bring attention to injunctive social norms e.g. how we should be driving, or treating people.

Feeling invisible - primed by the dark

Perhaps not surprisingly it's when we feel less seen by others that we are more likely to play fast and loose with morals. One experiment by Francesca Gino, a Professor at Harvard Business School and her colleagues found that people in a darkened room were more likely to cheat on a task than participants in a brightly lit room. Nearly 61% of people in the dark room cheated, compared to just 24% of those in a well-lit room.

This finding is validated by analysis of four years’ worth of US crime data either side of the spring daylight saving time switch and found that in the post daylight saving time (longer, lighter days) robbery rates were reduced by 51%, rape rates by 56%, and murder by 48%.

It’s easy to argue that this is because crimes are simply more difficult to get away with in daylight, but another study by Francesca Gino looked at the impact of wearing sunglasses on moral behaviour. People wearing sunglasses tended to be more selfish, keeping money to themselves rather than giving it to others and, perhaps unsurprisingly, they also reported feeling more anonymous. The researchers reported that what the participants in the darkened room and those wearing sunglasses had experienced was 'a psychological feeling of illusory anonymity' and it was this which increased morally questionable behaviours. Gino says, "We should probably pay more attention to the many ways in which we are in the dark."

Primed by brightness

We can deduce from Francesca Gino’s findings that, conversely, lighter and brighter environments increase self-awareness and reflective thought. Follow-up research supports this and further suggests that it may even lead to greater self-control.

At a very simple level, if we prime people with bright light, might it increase ethical behaviour or generosity? For instance, might the coffee and tea honesty box have been fuller if it had been placed under a bright lamp or next to a window? Or would an online tax form with a bright white background result in more honest declarations than a coloured one? Could light be used in courtrooms or other environments in which honesty is essential to a just outcome?

We know from the behavioural sciences of the importance of context on behaviour and the findings above further show how different lighting environments can subconsciously nudge behaviour. Ask the question what sort of lighting context could increase the pull and magnetism of your brand assets?

Consumer research is frequently carried out in the evening and we might need to think more carefully about how light may have a role in the behaviour we seek to understand.

We can also think how we might more directly use this type of simple priming in how we engage respondents in exercises from innovation concepts to completing questionnaires.

Priming confidence with a well-known face

Priming using certain images can actually improve our performance in demanding tasks. A recent study assessed whether priming men and women with images of authoritative, successful role models might help the speakers to perform better when speaking in public.

Male and female participants were asked to give a speech to a virtual room full of people - a reasonably stressful leadership task. Images of prominent political figures were placed in the rooms so that the speakers were able to see them clearly. Participants were split into four groups; two groups spoke with an image of either Angela Merkel or Hillary Clinton fixed at the back of the room, a third group faced an image of Bill Clinton and a control group had no image.

The researchers recorded the length of the speeches as a proxy indicator of confidence and good performance. The images of female role models seemed to improve the performance of women and the women who were primed with images of Hillary Clinton or Angela Merkel spoke 24% and 49% longer respectively. Women in the Angela Merkel group spoke for over four minutes, whereas those who saw no image or who saw Bill Clinton spoke for less than three minutes. However, none of the primes had any statistically significant effect on men’s speaking performance – they spoke for roughly the same amount of time no matter who they were looking at.

As a further measure of performance, independent evaluators were asked to rate all the speeches and tended to rate the speeches of women who had seen the female role models more highly than the speeches of women in the other test groups. Moreover, subsequent self-evaluations of each of the female speakers showed that those who spoke for longer perceived their performance to be better.

Could less confident social groups or those suffering from anxiety and shyness be primed to feel more confident in certain situations?

Could this thinking inspire new ways in which brands could harness the potential power of role models or authority figures in addition to their use as value short cuts and social norms?

Could we use this technique when we want to boost the confidence of respondents in research?

Maybe those mood priming posters of the 80s actually were creating the positive and resourceful states they claimed. It could be a whole new market for priming mantras and photography!

Priming using brands imbued with powerful meaning and associations

Brand logos and images have been found to influence behaviour in really interesting ways. For example, Apple and Google are often considered to be incredibly innovative and creative. IBM, however, might be considered a more traditional company, whereas Harrods brings to mind luxury.

Researchers have tested what effect brand logos and their associated personality traits might have on our thinking styles whilst noting that, “Apple has worked for many years to develop a brand character associated with nonconformity, innovation and creativity and IBM is viewed by consumers as traditional, smart and responsible.” Social psychologists Tanya Chartrand, Gavan Fitzsimmons and Grainne Fitzsimmons looked at the effect of priming participants with these two brands on a thinking task. Notably, they primed people subliminally ie participants saw one or the other logo for 13 milliseconds – not long enough for them to consciously register it. They found that priming people with an Apple logo made them think more creatively and laterally in a subsequent thinking task on ‘unusual uses for a brick’ than participants primed with an IBM logo. Judges were asked to rate the participants’ ideas and tended to rate the ideas from the Apple-primed group slightly higher - on average the ideas from the Apple-primed group scored 8.44 compared to 7.98 for the IBM-primed group, out of an overall maximum score of 10 for creativity. Apple-primed participants also came up with more ideas than did the IBM-primed group - 7, 8 or even 9 uses compared to only 6. Interestingly, in the same study, priming people with a Disney logo made them more honest.

“These experiments demonstrate that almost any brand that has strong associations with particular traits could have the capacity to influence how we act,” Chartrand said.

Similarly, another study found that the logos of thrift-focused stores in the US primed the concept of saving money. Logos of brands such as Walmart, Sears and Home Depot made people less willing to spend than logos for more neutral or less money-focused brands such as Coca Cola and Nokia.

In another study, which looked at behaviour and performance in racing car video games, those ‘driving’ in a car painted with a Red Bull logo and colour scheme tended to have faster times than other branded cars and to crash more often. Drivers primed by the logo tended to speed up and drive to the limit of their ability - and sometimes beyond their ability leading to crashes. To explain this effect, the researchers point to search results on the website brandtags.net, where users enter words or phrases they associate with brands. Nine of the 40 most commonly occurring terms for Red Bull are associated with speed and power and four are linked to risk-taking and recklessness.

They believe that, like the Apple and Disney examples, this is another type of subconscious brand priming - when the personality of a brand evoked in brand imagery unconsciously causes someone to act in ways consistent with that personality - almost like mental shortcuts to a set of emotions and values. We wonder what effect the ubiquitous real Red Bull cars driving around on our streets have on the driving behaviour of those around them!

Could product innovation and co-creation sessions potentially benefit from priming respondents to think more creatively and laterally?

The idea that other brands can prime consumers indirectly to be more receptive to another’s brand assets is an interesting area. We have seen this in creative collaborations (eg in fashion). But the area of cross category joint brand work is still largely untapped and is one where each brand could get disproportionate benefits from the association.

This also ties into the latest thinking about how brands grow and the need for constant recruitment to build penetration as opposed to focussing on frequency.

Colourful primes

A big part of what we see in our environment relates to colour, so it is not surprising that considerable research has explored to what degree colour primes our behaviour and how. Brands have long known this and spent much time debating a brand’s colours so we will not spend long revisiting this well known area. It is accepted that colour does and always has influenced our behaviour subconsciously and it is also recognised that the exact impact of different colours on different types of behaviour most likely varies across cultures. This is because our colour associations are, to a large degree, culturally learnt rather than innate.

For example, white and red mean different things in different regions and cultures – in the West white symbolises purity and cleanliness and red denotes passion and excitement, whereas in India white is associated with sadness whilst red is associated with love, marriage and spirituality. Therefore people can be primed in different ways in different cultures by colour. Meanings and associations of colour can also change over time.

From our point of view it is interesting to think about how colour can be used to prime behaviour indirectly, for instance as short cuts to gender stereotypes.

Primed by the colour pink: In contemporary Western cultures, pink tends to be associated with girls. Yet until 1880 boys and girls were dressed in any colour with both wearing pink and pale blue. (Take a second look at the image below - it's a picture of a paper doll boy). However, by the 1950s, this had begun to change, with pale blue typically associated with boys and pale pink with girls.

The behavioural effects of such gender stereotypes and associative effects have been illustrated in studies. One of the earliest studies on how colour might affect behaviour found that spending time in a bright pink-painted holding cell had a weakening effect on new male prison inmates. After just 15 minutes spent in the cell, they were found to be physically weaker and incidents of ‘erratic and hostile behaviour’ fell dramatically. The effect also lasted for 30 minutes after they were moved out of the cell. Alexander Schauss, who conducted the research, believed the colour had a tranquilising effect and promoted ‘muscular relaxation’.

Looking to the future, would this be replicable in 20 years' time? There is a growing movement in Western society towards the ‘depinkification’ (and deprincessification) of girls’ toys and in decades to come we could see far more gender-neutral colours, and consequently fewer connotations for the colour pink, resulting perhaps in less priming of gender stereotypes, preferences and behaviours.

SENSE 2: Subconscious behavioural influences triggered by smell

Smells and odours in our environment can also influence our behaviour. Below we look at studies which have used smells to prime people in several different ways - to be tidier or cleaner, to influence what they chose on a restaurant menu or even to increase gambling spend.

Primed to be clean and tidy

One study investigated the impact that the smell of cleaning fluid might have on how clean and neat we are. Psychologists at the universities of Utrecht and Radboud in the Netherlands first asked students participating in the experiment to complete a questionnaire sitting in a cubicle. There was a bucket of water in the room with them and it gave off the odour of a lemon scented all-purpose cleaner. A control group completed the questionnaire without exposure to the scent of all-purpose cleaner. Once they had filled in the questionnaire they went to another room (with no lemon scent) and were given a particularly crumbly biscuit to eat. They were filmed eating the biscuits and, in comparison to the control group, the lemon scented cleaner primed group cleaned up the crumbs substantially more often. The smell of cleanliness had primed them to behave in a clean and tidy manner. In a subsequent study researchers tested the impact of three different odours in the same way: an orange odour (pleasant, but with no anticipated association to cleaning), a grass odour (also pleasant, but with no association to cleaning), and a sulphur odour (unpleasant, and also not related to cleaning). Participants subjected to the smell of sulphur exhibited much less cleaning behaviour than those exposed to the more pleasant smells.

A similar study by a team of Dutch social psychologists used a citrus odour in train carriages and found that less littering occurred in the scented carriages than the unscented carriages. Weighing the amount of litter not in bins but left on the floor or seats at the end of 18 journeys showed that there was far less litter in terms of both number of items and weight. Although these findings need further investigation and replication, they illustrate how we might usefully be primed by the smells in our environment.

How pleasant smells can prime us to spend or gamble more

We can use smell in other environments too. For instance, a study by Alan Hirsch tested the effect of different scents in a Las Vegas casino over a single weekend and found that gamblers put as much as 45% more cash into a slot machine when the room was doused in a pleasant scent as opposed to a staler, less pleasant smell or if there was no smell. Moreover, the effects were greatest on Saturday morning when the scents were at their strongest. Spending actually increased by over 53% during that period and tailed off slightly to 34% by Sunday afternoon as the pleasant smell became more faint (although still noticeable). Hirsch believes that the pleasant smell was linked to memories, inducing ‘nostalgic recall’ and creating positive emotions and a stronger ‘gambling mood’. The stronger the pleasant scent, the greater the gambling.

In a different trial, Hirsch also found that customers were happy to pay $10 more for a pair of Nike trainers in a floral scented shop than in an unscented one. Customers in the scented shop were also more likely to buy the trainers too.

Although it may be harder to conceptualise a brand-related smell, this is a powerful way to prime behaviour both directly and indirectly.

Priming can change behaviour in a context and make those in that context behave in a way that could make them more receptive to your brand assets [physical and mental levers].

What are your brand’s smells that connect directly to your brand associations? [It is an interesting idea that all brands could have an associated scent or smell]. And what smells and scents could indirectly prime receptiveness to your specific brand messages?

We could also, much more simply, use scent priming to create much more realistic research contexts.

Priming what we eat

A French study demonstrated how priming using different food odours could change what people chose to eat in a restaurant, simply through association. Researchers used the smells of melon and pear to alter behaviour. The word ‘melon’ might prompt you to think starter and possibly, Parma ham. Think of the word ‘pear’ and you might well make an association with dessert and chocolate, or warm, spiced, red wine.

Those participants in a subtly melon-infused room went on to select more starter items with vegetables (such as asparagus salad) as opposed to higher calorie entrees (eg quiche Lorraine) and to choose fewer fruit based desserts from a menu; whilst those in a pear-infused room chose more fruit-based desserts (eg pineapple carpaccio as opposed to chocolate profiteroles) and fewer veg-based starters and mains. The researchers think these results suggest that the subconscious perception of the melon and pear fruity odours may activate a ‘fruit and vegetables’ concept, but also a concept of the context of consumption ie when or during what part of the meal we tend to eat these types of foods.

In an arena where there is considerable discussion about reducing obesity, increasing healthy eating and reducing consumption of high calorie foods, being able to prime food selection choices is an interesting idea, worthy of further exploration.

The hazards of priming with smells

Of the five senses olfactory priming is one of the most difficult to achieve. Sense of smell varies by individual and is a very personal thing. Individually, we vary widely in our ability to detect and be aware of odours; some people don’t detect them at all while others are highly sensitive. One builder tried flooding his showrooms with the scent of hot apple pie and freshly ground coffee but his staff complained the scents were overwhelming.

Moreover, something that is faintly pleasant to one, might be overpowering or just plain disgusting to another. Our responses to smells will vary depending on association and what emotions they trigger in our memory. Even if you've never read Proust you're probably familiar with what has become known as the Proust effect, where the taste of a small cake called a madeleine swamps Proust's protagonist in A La Recherche du Temps Perdu in a sudden and overwhelming melancholy.

Scent is also one of the senses we are least aware of, and one which can confuse us easily. Often, feedback from our other senses guides us towards what we guess the smell actually is and if the rest of the sensory context - what we see and hear - does not match the smell, we can become confused. Sometimes a smell needs a context to allow us to place it correctly.

Dutch researchers, Professors Monique Smeets and Ap Dijksterhuis found some surprising results whilst presenting different odours to participants in lab based experiments. Smells of rotten eggs, pizza and brownies were labelled by participants as ‘sweaty’, ‘computer-smell’, ‘rubber’ and ‘stale lab smell’. Participants needed the context behind the smell as much as the smell itself to detect what it might be.

Similarly, a £1.4 million campaign prepared by liqueur maker Disaronno Originale to waft the pleasant smells of Amaretto liqueur around the London Underground in the run-up to Christmas in 2002 was withdrawn at the last minute due to sudden fears it might be confused with a cyanide gas attack by terrorists. Cyanide has a bitter almond smell…! The context accompanying smells matters.

SENSE 3: Are you listening carefully? Then I'll begin. The priming power of sound

Sound can prime our behaviour and our perceptions too and is an important cue in our environment. Engineers often tweak the sounds and acoustics of new products - even recreating what are now essentially obsolete mechanical sounds - to provide us with cues to help us perceive whether a product is working correctly or safely, or that we have used it optimally. For example, the comforting ‘clunk’ of a car door closing tells us that it is safely closed and the faked noise of a camera shutter (totally unnecessary on new digital cameras and for smartphone photography) gives us feedback that we have successfully taken a shot.

We also think crisps are fresher if we hear an accompanying (and satisfying) crunch sound - even when they are stale. A study by Massimiliano Zampini and Charles Spence found that it was possible to modify people’s perception of the degree of crispness or staleness of a Pringles potato chip, by using a microphone and speaker system to modify and play the sound of them biting into the potato chip into the testing booth at a comfortable, audible sound level. They either augmented or attenuated the high frequency sounds of the bite, or played the entire sound slightly louder and found that people rated the Pringle chip as crisper when high frequency sounds were augmented or when the overall sound was slightly louder.

Priming expectations and perceptions of food and drink

We often believe that taste is the crucial element behind whether a meal is perceived as good or not. However, the environment in which food and drink are served, and the ‘sensory congruency’ between the environment and the flavours, can play a large, yet subconscious role in modulating our perception of, and responses to, food and drink, and sound is key. Celebrity chef Heston Blumenthal and experimental psychologist Charles Spence have carried out a number of experiments looking into the sensory experience of a meal.

One particular study focused on whether sound can augment taste and prime our perceptions and judgement of a meal. They demonstrated that people rate bacon and egg ice-cream as tasting significantly more ‘bacony’ when listening to the sound of sizzling bacon than to a farmyard of clucking chickens.

In a second experiment, people rated oysters eaten while listening to the sound of the sea on an iPod (ie the sound of seagulls squawking and waves washing gently on the beach), as tasting significantly more pleasant than oysters eaten while listening to the farmyard noises. Taken together, these results highlight just how dramatically environmental sounds can influence (or bias) people’s perception of food.

Blumenthal commented "We ate an oyster while listening to the sea and it tasted stronger and saltier…Our tests revealed that sound can really enhance the sense of taste".

These findings led directly to the introduction of the unique ‘Sound of the Sea’ dish at Heston Blumenthal’s restaurant The Fat Duck. Diners are presented with a plate of food that is reminiscent of a beach (with foam, seaweed and sand all visible on the plate – see image below). The dish also comes with a mini iPod hidden inside a sea-shell, with the earphones poking out. Diners are encouraged to insert the headphones (whereupon they hear the ‘Sounds of the Sea’ soundtrack) before starting to eat. Wearing headphones also has the advantage that it focuses the diners’ attention on the food itself, by blocking out other sounds in the room and immediate environment.

Charles Spence has also been collaborating with British Airways to improve the in-flight eating experience using sound. Researchers have discovered that our ability to taste is reduced by 30% in the air so to combat that, the airline has launched a 13 track playlist (based on Spence’s research findings) to match the food served on board and improve passengers’ eating experience. The playlist is available on its radio channels on long-haul flights.

For example, BA suggest listening to Scottish singer Paolo Nutini whilst eating a Scottish smoked salmon starter, whilst Madonna and James Blunt are suggested as dessert accompaniments because they are thought to boost sweeter flavours, and Otis Reading is thought to help bring out the bitterness of after-dinner chocolates.

For example, BA suggest listening to Scottish singer Paolo Nutini whilst eating a Scottish smoked salmon starter, whilst Madonna and James Blunt are suggested as dessert accompaniments because they are thought to boost sweeter flavours, and Otis Reading is thought to help bring out the bitterness of after-dinner chocolates. Other research by Charles Spence has shown how background music can impact perceptions of the quality of wine. He conducted a series of music-wine pairing events with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the Antique Wine Company in London. Amongst other revelations the experiment showed that people rated a Bordeaux wine as tasting significantly more enjoyable when paired with a heavy string quartet - something like Tchaikovsky’s String Quartet No 1 in D major, K285 - while a white wine such as Pouilly Fumé was more enjoyable when listening to Mozart’s Flute Quartet.

We can also detect the difference between the sound of hot and cold fluid being poured. An experiment by psychologists Carlos Velasco, Charles Spence and their colleagues found that people can tell whether water is hot or cold solely on the basis of the sound that it makes when poured into a receptacle made from one of four different materials (glass, porcelain, paper and plastic). A further experiment illustrated how people’s perception of temperature can be changed by artificially modifying the sonic properties of the sound that hot and cold water makes when poured into a receptacle. With this knowledge we can think about priming our perceptions of what we are about to drink.

What sounds does your brand use to prime people to be more disposed to their category or brand cues?

How could sound augment an experience or research context?

How could sounds augment packaging? What sounds does your packaging make and what expectations or associations does it prime?

SENSE 4: Touchy feely

Our sense of touch and feel can impact on our emotional, behavioural and intellectual response to both people and objects.

Temperature can prime perceptions of warmth and generosity

For example, holding a hot cup of coffee has been found to lead us to form warmer impressions of others.

• In one study, Yale University psychologists showed that people given a description of a fictional character judged them more warmly, describing the person as more good-natured and generous, if they had held a warm cup of coffee earlier, but were less likely to be so well-disposed towards the person if they had held an iced cup of coffee previously.

• A second study revealed that people are more likely to give something to others if they have just held something warm (in the experiment participants held a hot therapeutic pad) - but more likely to take something for themselves if they had held a cold ice pad.

People can also be primed by other sensations to make different social judgments. Joshua Ackerman and his colleagues conducted a study investigating a number of haptic effects; texture, weight and hardness.

- How texture can prime conformity or confrontation: Participants read an ambiguous social interaction between two people after completing a five-piece jigsaw puzzle. In one version of the puzzle, the pieces were covered in rough sandpaper, and in the other, they were smooth. Those who completed the rough puzzle perceived the situation as being confrontational and more competitive than those who completed the smooth puzzle.

- How weight can increase the perception of importance: Holding a heavier clipboard when answering a survey about whether various public issues should receive more or less government funding led men (but, interestingly, not women…) to allocate more money to those issues.

- How touching a soft object can prime perceptions of kindness: Participants in a study were asked to watch a magic trick, and to try to figure out how it was done. Beforehand, they were asked to examine the object to be used in the trick - either a soft piece of blanket or a hard wooden block. After watching the magic trick they were then asked to give their impressions of two individuals - an “employee” and the “boss” - involved in a hypothetical interaction. Those primed by touching the soft blanket evaluated the employee as being kinder than those given the wooden block to examine.

- How the shape of a wine glass can impact our perception of the taste and quality of wine: Other studies show that the shape and feel of a glass can affect our perception of the quality and taste of wine and champagne. The size, weight, shape and even the colour of the glass can all have an impact on our perception of the aroma, flavour and overall quality of the wine.

These powerful subconscious textural primes can change how we view a brand, how we judge a concept.

Do we spend enough time thinking about these touchy feely elements?

In a recent piece of work looking at successful beauty therapists, we found that giving the customer the beauty product to hold [not the tester] had a positive impact on purchase. The sensory prime tapped into endowment bias and was believed to lead to higher conversion.

MULTI-SENSORY PRIMING

We can probably all recall a meal or a drink in a bar where the experience was pretty special, perhaps even magical. Or where something everyday was transformed into a heightened experience. But if we're asked to define the formula for how the components connected together to create that experience, we might be at a loss.

Professor Charles Spence believes he knows. He believes that matching each of our sensory impacts to an experience can augment our experience as a whole. So 2 + 2 + 2 will actually equal 10 rather than 6. By matching the associated ‘sound, smell and touch’ of a taste, we perceive and rate the taste to be far better than we might rate it with no other sensory effects.

He tested this in a recent study , where he found that an identical whisky was rated differently by consumers depending on which ‘themed room’ they drank the whisky in.

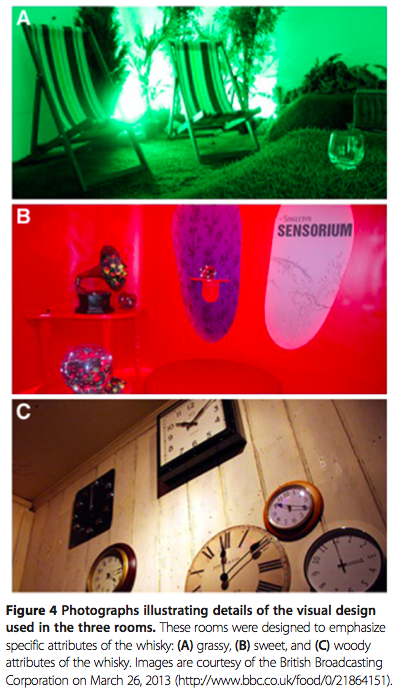

At a whisky-tasting event in London, Spence and his colleagues designed three ‘tasting rooms’ (see image below).

At a whisky-tasting event in London, Spence and his colleagues designed three ‘tasting rooms’ (see image below). - The ‘grassy’ room had grassy turf laid on the floor, green-leafed plants placed around the walls, green lights, and three deck chairs. A summer soundscape of birds singing and the sound of wind rustling in the trees played in the background.

- The ‘sweet’ room was brightly coloured and illuminated by round red globes, with a bowl of ripe red fruits in the centre. High pitched piano music was played in the background.

- The ‘woody’ room had wood panelling and was dimly lit with a soundtrack of leaves and twigs being crunched underfoot.

The results showed how people rated the whisky differently depending on which tasting room they were in. For example, the whisky was rated as being significantly grassier in the ‘grassy’ room, significantly sweeter in the ‘sweet’ room, and significantly woodier in the ‘woody’ room. Participants’ ratings of the smell and flavour changed by about 10% to 20% as a function of the room. Overall, the participants liked the whisky most when they tasted it in the ‘woody’ room. While this finding is interesting from the specific point of view of whisky, the broader implications are perhaps more significant - that every sensory element can feed into our perceptions of a consumption experience.

These results present an opportunity to enhance people’s experience of taste by designing what Spence calls congruent multisensory environments; in other words in making the environment match up with the flavours people are tasting.

This has significant implications for many consumer environments beyond the restaurant and bar; for example in-flight meals, cinemas, festivals and concerts.

Conclusion

In this article we have shown how powerful sensory priming can be and just how sensitive we need to be as marketers and researchers to the environments we work in. Where we might already think about which words and phrases might prime thinking and behaviour, it is unlikely we give sensory priming the detailed structured thought it deserves, beyond maybe the role of colour. This article has drawn attention to how light or darkness, inspirational figures or brands and smells, touch or sound can subconsciously influence our behaviour.

As stated in our first article about priming, we should be thinking strategically and executionally about which sensory primes we want to use to increase the direct and indirect magnetism of our brands. We need to think how we can not only directly prime connection to a brand but also indirectly, by making a person more receptive to a brand’s existing subconscious connections and dispositions via what they see, smell, hear and even touch.

In consumer research we need to think more about how we might embrace the power of sensory priming, for example to increase a respondent’s confidence, generosity or creativity whilst also being aware of how the sensory environment might be priming people inadvertently and what we can do to avoid this.

See more at www.thebearchitects.com

@thebearchitects