By Crawford Hollingworth, founder of The Behavioural Architects.

British households are struggling more than ever to pay their fuel bills as energy prices rise in what is still a difficult economic climate. One in ten families have already defaulted on fuel bills, and another 15% say they will be unable to pay their next bills. One in three homes say they are now trying to ration their energy use.[1] This article looks at how we can use insights from the behavioural sciences to help us to save money on energy bills over Christmas and beyond.

Savings in the home

Saving energy at home is something we all know we should do more of. But we procrastinate - sometimes we don’t get around to putting in that loft insulation, we have other things on our minds that seem more important than analysing our energy bills, and sometimes we are just not in the habit of switching off lights or remembering to turn down the thermostat when we go out. And if it’s cold outside turning the heating down seems very unappealing in order to save money on a bill not due for weeks! Sometimes we have no information or feedback on energy costs so we don’t really know what turning an extra light on or having a longer shower means cost-wise. But insights from behavioural sciences can help us. There have been many trials run on ways in which we can use such insights to nudge households into reducing energy consumption.

Giving real-time feedback

Smart meters, like the mpg and mph displays in our cars, give in-the-moment feedback to enable us to have greater control over our behaviour. “Learning is much more likely if you get immediate, clear feedback after each try.” say Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein.[2] Over the past few years, smart meters have become more widely available and can help steer people into reducing energy in the home. One study found that using a smart meter reduced electricity consumption by 5.3% on average.[3] Another study looked at 12 pilot programmes using smart meters across North America, Australia and Japan and found that using a smart meter in the home reduced consumption in the range of 3 to 13%, or 7% on average.[4] Early trials have also shown that placing smart meters in locations where we are more likely to see the feedback – for example – on the stand-by screen of a TV - has an even greater effect on reducing energy consumption. British Gas have recently launched a mobile app so you can turn your thermostat up or down remotely when you are out, in case you are delayed longer than you thought or want the house to be warm when you come back from a week away.

The modern day coin in the slot

There are also a surprising number of prepayment schemes across the world, for example, in the US, New Zealand and South Africa. People who pushed coins into the slots of the first prepayment meter versions of these in the early 1900s were well aware of the true cost of heating and energy use - although they probably didn't equate this with what behavioural economists call ‘loss aversion’ - that's the bit which required them to part with actual cash before they could turn on a light or get warm. Loss aversion tells us that we dislike losses more than we enjoy equivalent gains, especially when the loss is made more salient by parting with cash in the moment, rather than paying a distant direct debit bill. The modern version of the pre-pay electric meter uses loss aversion in the same way, translating energy used directly into monetary cost (rather than displaying energy output). This has been shown to be effective in a number of places in North America such as Arizona state, Ontario and Alaska, where pre-pay meters have typically reduced electricity consumption by 13-15%.[5]

Opower’s Home Energy Reports and social norms[6]

The most well-known interventions to reduce energy consumption are run by the energy software company Opower across the United States. They work with utility companies all over the US to send out carefully designed, consumer-friendly Home Energy Reports, which use what behavioural scientists call descriptive social norms (what everyone else is doing) to tell people how much energy their neighbours are using. They include statements like “You are ranked #41 out of neighbors like you" or "You used 19% more energy than your efficient neighbors". These interventions show that when above-average consumption households realise how much energy they are using in relation to their more conservative neighbours, their energy consumption goes down. Below average users are rewarded with smiley faces on their bills to limit what researchers call ‘the boomerang effect’ – when energy consumption of below average users actually increases as they learn that their neighbours are using more energy than they are, prompting the potential response ‘If no-one else is trying to save energy then why should I try so hard?’.

Chunking the steps to saving energy

Opower has also recognised that although people may want to reduce their electricity consumption, especially on seeing how they compare to their neighbours, they may not know how to. So to make the task easier and break it down into different steps (or ‘chunking it’), they have added a second component to their energy reports. The ‘Action Steps Module’ includes meaningful and salient energy saving tips and easy-to-action steps like "Turn your thermostat down by 1 degree and it could save you 10% on your bill".

Results are promising for Home Energy Reports. Figures across 14 different randomised trials for 600,000 households across the US show that the average program reduces energy consumption by 2%. In real terms that's comparable to turning off an air conditioner for 37 minutes each day or turning off a light bulb for 2 hours each day. For the heaviest energy users, the energy reports actually reduced consumption by as much as 6.3% while existing low energy consumers sustained low consumption levels.[7] So this Christmas just making sure you turn off your Christmas tree lights when you leave the house (and overnight) could have a similar effect.

Said with a little added Authority

Robert Metcalfe, a behavioural economist based in Chicago, has run similar trials on households here in the UK but with a small difference. Rather than the Home Energy Report coming to consumers signed by the usual mid-level manager at the utility company, he tested to see what happened if the report was signed instead by the company's CEO. Authority bias tells us that sometimes we are more likely to adjust our behaviour if information comes from an authoritative figure. And Metcalfe found this to be the case - receiving a report from the CEO doubled the effects seen in the Opower reports.[8]

Changing habits for good

How long do these energy saving impulses last for? And if the reports stop coming what happens to consumption later on? These questions were investigated in a recent working paper by Hunt Allcott and Todd Rogers[9] who tracked 78,000 households on the US West coast from 2008 to 2012. Using a randomised controlled trial they looked at the short and long term impact of the Home Energy Reports sent by Opower, either on a monthly or quarterly basis. As before, the reports helped customers to reduce their energy consumption. Yet Allcott and Rogers were interested in the patterns of consumption during the trial and how long these effects lasted after the end of the trial. They found evidence of what they term ‘action and backsliding’, eg when the monthly energy report arrived, energy usage would fall noticeably over the next 10 -12 days as households were reminded of saving electricity but then, as they forgot their energy report, would begin to creep back up again – until the next report arrived on the doormat. Over time though, this cyclical effect disappeared and the fall in energy use became persistent as

- new habits became more engrained, such as automatically switching off lights or turning down the thermostat if leaving the house;

or

- as small but permanent changes in the technology were fitted in the house such as installing energy saving light bulbs.

These effects are useful for energy firms and policymakers because they could save money for the utility companies as well as the customer. Special interventions like Home Energy Reports – which cost money to produce - might only need to be sent out for perhaps 18 months before permanent changes in energy consumption become engrained as habits change and technology and appliances upgrade energy efficiency. Equally, the research also tells us how many reports need to be sent, or how often reports are needed permanently to reduce energy consumption in the home. Too few and it might not be enough to help consumers make their reductions in energy consumption permanent.

Reframing the true cost of your tumble dryer

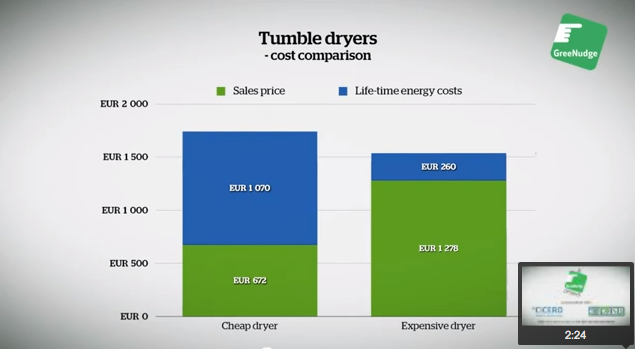

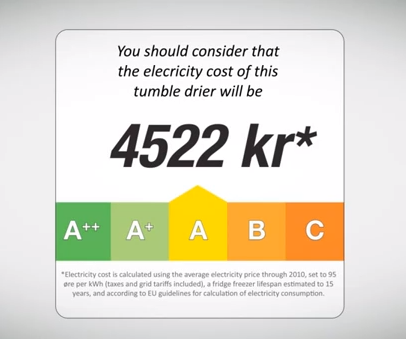

Of course, turning off lights and having shorter showers are all great things to do to reduce your energy consumption. But buying energy efficient appliances in the first place can make a big difference to energy savings over the long term. And yet the sales prices of energy efficient appliances are often more costly which is unappealing for many consumers. GreeNudge, a Norwegian not-for-profit organisation recently teamed up with Elkjøp, the biggest electronics retailer in Scandinavia, to set about reframing the cost of a new tumble dryer to guide consumers into buying the more energy efficient one. People tend to focus only on the sales price and don’t calculate the running energy costs over the typical lifetime of the appliance often selecting the cheaper dryer (see Figure 1). Yet the cheapest dryer could end up costing you more in the long run if it's not energy efficient. The most energy efficient model uses half the electricity of the average model. So Elkjøp added another label to each dryer on sale letting customers know how much energy it would cost them over ten years of normal use (See Figure 2). This acted as a new anchor or reference point for customers, reframing the true cost to help people realise that spending a little more now, could mean spending less in the future on energy bills. The new labelling system combined with the retrained sales team was successful and helped consumers buy dryers that used 5% less energy, equivalent to one in ten customers buying the most efficient dryer.[10]

Figure 1: Comparing long-run costs of tumble dryers

Figure 2: Elkjøp’s long term energy use labelling for tumble dryers

In conclusion, we have seen once again how small behavioural interventions or nudges can radically alter behaviour. Tiny steps can build to major behavioural change - just turning off the TV at the socket each night can save a significant amount of energy. We have also seen how changing the anchor from cost today to cost over a lifetime can turn conventional choice architecture on its head.

[1] The Guardian, “A third of families ration fuel as soaring power prices force 'heat or eat' dilemma.

New research reveals 10% of people have already defaulted on energy bills” 2 December 2012

[2] Thaler, R. Sunstein, C. ‘Nudge’, p82, 2008

[3] Houde, S., Todd, A., Sudarshan, A., Flora, J.A., Armel, K.C., ”Real-time Feedback and Electricity Consumption” May 2012

[4] “Faruqui, A., Sergici, S., Sharif, A. “The Impact of Informational Feedback on Energy Consumption – A Survey of the Experimental Evidence” Energy, Volume 35, Issue 4, April 2010, Pages 1598–1608

[5] ibid.

[6] Opower Home Energy Reports: http://opower.com/what-is-opower/reports/

[7] Allcott, H. “Social norms and energy conservation” Journal of Public Economics, 2011

[8] http://www.britac.ac.uk/policy/Nudge-and-beyond.cfm

[9] Allcott, H., Rogers, T. “The Short-Run and Long-Run Effects of Behavioral Interventions: Experimental Evidence from Energy Conservation” NBER Working Paper, October 2012

[10] GreeNudge – ‘Triple win tumblers’: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XLwXK8OfjrU&feature=plcp and http://www.greenudge.no/en/studier/artikkel-under-studier/