We often can't help but point out the irritating habits of others…'You never turn the lights off..', 'Could you put your dirty plate in the dishwasher once in a while?', 'Stop fiddling with your nails, it's really annoying..' and so on. Perhaps though, we are less aware of our own habits and couldn't begin to guess at the routine behaviours that drive people we don't know particularly well. And that's not surprising because sticky habits tend to be bedded down deep into automaticity. So how can we measure the strength of a habit and how embedded it is in our routine? Would it shift easily if we tried to dislodge it or is it deeply locked in?

This article is the third and last in our series on habits. Part One looked at the theory behind habit formation and what we can do to put a stop to stickily engrained bad habits. Part Two focused on ways of creating new habits in our lives. Part Three looks at why it is useful to be able to measure the strength of existing habits and just how we might do that.

1) Why measure habits?

Experts involved in behaviour change have realised that it is often useful to be able to measure habit strength - for two main reasons:

- To obtain a behavioural benchmark: It's useful to measure the baseline and get a benchmark of existing behaviour and the strength of habits in order to assess the effectiveness of any behaviour change intervention to amend (by increasing or decreasing habit strength) or break those habits. Does someone’s behaviour change as a result of a particular intervention and by how much? To what extent can an intervention weaken or strengthen an existing habit? To what extent does it create long-lasting change?

- To understand how hard we might need to work to shift an habitual behaviour: What type of intervention is required? How much effort needs to be put into an intervention and for how long? For some individuals it might take more effort to change or bed in new habits – for instance, people living alone often have more habits which are more deeply embedded than those living with other people, probably because the latter have to adapt their routines to others and are simply not able to be so set in their ways. Another crucial question might be when can the intervention be discontinued? For example, a recent working paper by Hunt Allcott and Todd Rogers looked at the energy saving behaviours of households receiving Opower’s Home Energy Reports to see when the changes people make in their energy usage behaviour become fixed. They have found that long term behaviour change usually becomes embedded after a number of months, meaning the specially designed energy reports – which are a little more expensive than standard ones – could be phased out once household energy use habits have been changed for good.[1]

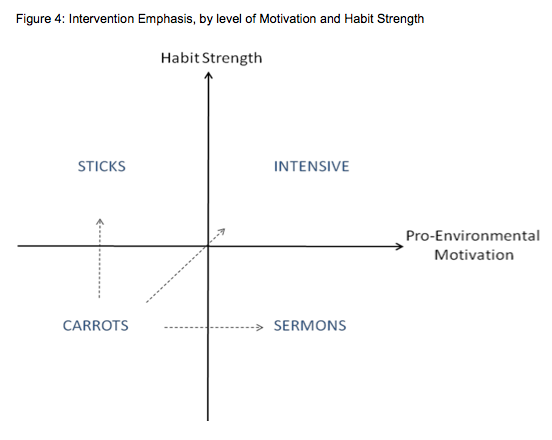

DEFRA have developed a great framework with which to think about different approaches for those with stronger or weaker habits.[2] They suggest measuring both an individual’s strength of habit and also their willingness or motivation to change and plotting these indicators against each other to create a matrix (see image). In doing this we can classify someone into one of four different camps:

- those merely needing little carrots to tip over into a new behaviour

- those with stronger habits requiring quite firm ‘sticks’ to increase both motivation and change habits

- those with weak habits but strong motivation who might simply need short ‘sermons’

- those needing quite intensive efforts to help change habits even when their motivation is high

Figure 1: A matrix for habits, motivation to change and sustainable lifestyles. Source: DEFRA

2) What measures can give us an idea about habit strength?

To measure habits effectively, we need a good definition of what makes a habit. Behavioural scientists usually define a habit as multifaceted with three key features: automaticity, frequency of repetition and a stable context. And out of all the features, automaticity is – currently at least - considered to be the key determinant of habit strength by behavioural scientists. So these three indicators could be a good starting point. Beyond these, there may be a couple of other useful things to look at: the existence of a reward and whether someone considers a routine or habitual behaviour to be part of their identity:

- Automaticity – How automatic a behaviour becomes is now considered to be a far better indicator of habit strength than frequency of past behaviour and whether a behaviour is fully embedded. Automaticity exists when the behaviour is unintentional or uncontrollable and if we do not consciously initiate it but simply find ourselves doing it or having done it. Automaticity is also present when other tasks and actions are able to be performed alongside the habitual behaviour in such a way as to make us more efficient (automaticity enables multi-tasking), or if we can think about other things whilst performing that behaviour.[3] So measuring these indicators is an essential part of estimating habit strength.

- Frequency of repetition – This usually means the frequency of past repetition, or the number of times daily or weekly the behaviour is carried out. The first measures of habit relied solely on a history of repetition or frequency of past behaviour, but experts now generally agree that this is a limited and potentially misdirecting measure. For example, a doctor might send many patients to the operating table, but you’d hope that the doctor doesn't make a habit of this behaviour, and rather, is making a conscious, carefully-thought out decision. Habit strength might also vary even though the frequency of behaviour remains the same. For example, someone taking a daily pill might initially take the medication as a conscious and deliberate action (ie with no habit), but after several weeks they may have developed a strong habit so that the behaviour has become automatic. The frequency of behaviour - the regular daily pill - has stayed constant throughout, however.

- Stable context – As we discussed in Part Two, performing a behaviour in the same context each time is often a key feature of habit. The context might be the physical location or environment, the social context, or a particular time of day. The context acts as the trigger or cue to initiate the behaviour and so can help to build or be indicative of a habit and therefore worth recording. However, it may not always indicate habit strength. There are plenty of engrained habits that are prompted by the context - finding ourselves in the kitchen in the morning we might automatically fill the kettle, once we get to the gym we set about our standard routine without giving it much thought (most likely heading for the same machine if we can get it), we also tend to route ourselves repetitively around the supermarket aisles, and there are undoubtedly myriad other activities we embark upon triggered by context. It may still be useful to collect or record this information, but relying on it as a sole indicator for habit strength could be misleading.

- Reward or feedback - As we also discussed in Part Two, the presence of a strong reward, motivation or some sort of feedback created by the behaviour can help to build a habit. However, like context, the presence of a perceived reward may not reliably indicate habit strength. Trying to gauge the size or strength of reward may not translate to strength of habit. There are some habits where the reward may be small or perceived as small by the respondent, or even be subconscious and unrecognised by the respondent. There may be other behaviours with large (perceived) rewards, yet the behaviour may not yet be a habit if the context is unstable or if the rewards are not yet recognised by the respondent. Rewards are often very complex – there could be several which overlap, making them difficult to measure and single out.

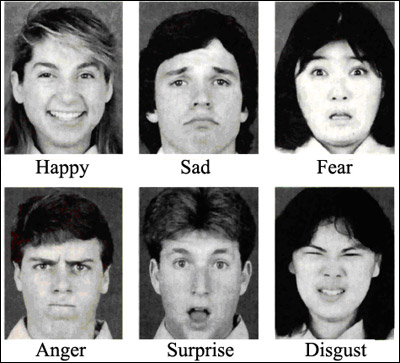

As with context, it may still be useful to record this information, but relying on it as a sole indicator for habit strength could be misleading. And measuring rewards is problematic (for the same reasons as we discussed above), particularly for self-report. It may be more effective to gauge what rewards are, using visuals and words to prompt emotional associations. For example we might get respondents to select words from a word cloud, or choose from a bank of images. Another technique we use is to ask respondents to select the Ekman emotion they feel most accurately captures their emotion in response to something. (Ekman found that there are a series of universal emotions such as anger, fear and happiness. See image)

As with context, it may still be useful to record this information, but relying on it as a sole indicator for habit strength could be misleading. And measuring rewards is problematic (for the same reasons as we discussed above), particularly for self-report. It may be more effective to gauge what rewards are, using visuals and words to prompt emotional associations. For example we might get respondents to select words from a word cloud, or choose from a bank of images. Another technique we use is to ask respondents to select the Ekman emotion they feel most accurately captures their emotion in response to something. (Ekman found that there are a series of universal emotions such as anger, fear and happiness. See image)

- Identity is sometimes thought to be influenced by habitual behaviours. We carry out a behaviour, speak in a particular way, or even have certain thought processes or reactions to events which we define as ‘typically us’ and might feel strange if we did not do, or did something else. Moreover, we often seek to be consistent with our past behaviours in order to avoid what psychologists call cognitive dissonance – when we feel discomfort when our attitudes and beliefs do not match our behaviour. For example, research has found that people are more likely to vote if they are reminded of their identity as a past voter. As Bas Verplanken and Sheina Orbell point out “habits are part of how we organize every-day life and thus might reflect a sense of identity or personal style.”[4] Whilst this may not be a factor in all habits, some could define someone and, in their eyes, express their identity, so getting a sense of how much a habit or behaviour is considered part of someone’s identity could be useful. However, some researchers believe that self-identity is not a useful component of habit to measure.[5] Moreover, it could be a tricky thing to assess through self-report – are we really aware of what is 'typically me’?

3) Some simple tools to measure habit strength – the Self-Report Habit Index

Armed with the five indicators we outlined above - frequency, automaticity, stable context, reward and identity - we can begin to think about how best to measure some or all of these in order to gauge habit strength. Observation can be a reliable and unobtrusive way of measuring, but can sometimes be limited since we can only identify how often something is performed and have to infer from this if a behaviour is actually a habit. Whether the action is automatic is much harder to measure from observation only. So non-obtrusive, simple self-reporting which can get respondents to think reflectively about daily activities can sometimes be a better approach.

One of the most widely recognised self-report measures used by behavioural scientists currently is the Self-Report Habit Index (SRHI).[6] The 12-point SRHI is comprised of questions which assess three of the five elements outlined above:

- Frequency or history of repetition

- Automaticity

- Identity

For each question, respondents answer the degree to which they feel it affects them using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from agree (1) to disagree (7).

Self Report Habit Index (SRHI)

|

|

Behaviour X is something . . . |

Habit definition subscale |

|

1 |

I do frequently. |

History of repetition |

|

2 |

I do automatically. |

Automaticity |

|

3 |

I do without having to consciously remember. |

Automaticity |

|

4 |

that makes me feel weird if I do not do it. |

Identity |

|

5 |

I do without thinking. |

Automaticity |

|

6 |

that would require effort not to do it. |

Automaticity |

|

7 |

that belongs to my (daily, weekly, monthly) routine. |

History of repetition |

|

8 |

I start doing before I realise I’m doing it. |

Automaticity |

|

9 |

I would find hard not to do. |

Automaticity |

|

10 |

I have no need to think about doing. |

Automaticity |

|

11 |

that’s typically “me.” |

Identity |

|

12 |

I have been doing for a long time. |

History of repetition |

Source: Verplanken and Orbell (2003)

AUTOMATICITY ONLY: THE ARGUMENT FOR A SIMPLER MEASURE THAN THE SRHI

As with any measure, there are limitations. Respondents are highly likely to get tired of answering a 12 point questionnaire, especially if it needs to be done daily or for different activities. Moreover, because new habits take on average 66 days to form, any measurement of new habit formation needs to be tracked for at least this length of time. This is a long time to engage with respondents![7] As Phillippa Lally and her colleagues observed during a three month study of habits “It is difficult to assess the extent to which completing the same questions every day affects people’s responses.”[8] Fewer questions (like those testing only for automaticity) might therefore be easier and quicker to answer which could lead to more reliable results.

One solution to this problem could be to measure habits simply through testing a subscale of the SRHI. Several studies and pieces of analysis have revealed that we can get the same results using various subscales using some or all of the 7 items which measure automaticity.[9] For example, Benjamin Gardner at UCL and his colleagues have developed a 4 item automaticity subscale called the Self-Report Behavioural Automaticity Index (SRBAI) and found it to be reliable. They asked seven different social or health psychology researchers with expertise in social cognition (but little knowledge of habit theory) to give their views on which of the 12 elements were most crucial. Items 2, 3, 5 and 8 were most confidently and consistently judged to capture automaticity:

- I do automatically

- I do without having to consciously remember

- I do without thinking

- I start doing before I realise I’m doing it

They then took four existing studies of habits (car commuting, cycle commuting, snacking and alcohol consumption), using the full datasets from the SRHIs and compared the full 12-item score with their 4-item SRBAI score. For all four datasets, the SRBAI score was strongly correlated with the original SRHI and was deemed to be a worthy and equal substitution.[10]

CAN WE BUILD AN EVEN BETTER MEASURE? Food for thought

At The Behavioural Architects we take the tools described above as a starting point, and have been applying other techniques used in behavioural science to increase the reliability of self-reporting. For example:

- Could the SRHI questionnaire be ‘chunked’ into a number of more manageable sections? Just changing the layout and way the questions are asked could improve responses

- Could the 7 point Likert scale be simplified and narrowed, reducing choice overload, yet still produce the same results?

- A specially-designed smartphone or tablet app might also improve ease of use and reduce any potential barriers to reporting.

- Online and mobile research could also be an advantage in increasing the reliability of self-reporting. Prompting respondents as they are performing the behaviour in the moment could likely lead to more accurate and regular reporting.

As any good researcher knows, self-report may also be a problem. Respondents might want to appear consistent or committed to building the habit or provide answers which they believe to be socially desirable or fit with the perceived norm.

In this case, ways in which we can simply observe the level of repetition and frequency may be better. For example, simple ethnographic observation might be a good solution or via video recording and analysis. These are good for open environments – airports, shopping centres, roads, but are more difficult to run in-home.

In this case, ways in which we can simply observe the level of repetition and frequency may be better. For example, simple ethnographic observation might be a good solution or via video recording and analysis. These are good for open environments – airports, shopping centres, roads, but are more difficult to run in-home.

For in-home tracking we might instead use technological devices to track behaviour and measure habit strength. For example, Unilever recently designed a toothbrush containing an accelerometer and gave this to a set of consumers to track how often and for how long they brushed their teeth.

Similarly, Dr Val Curtis at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine carried out a study to observe the habit of handwashing. She installed wireless sensors in motorway service station toilets – a movement sensor at the doorway and a second sensor in the soap dispenser – and found that of the 330,000 people using the toilets, a disturbing 32% of men and much more heartening 64% of women washed their hands with soap.[11] By observing the regularity by which consumers were brushing their teeth or washing their hands, we might well be able to deduce the strength of habit, or least whether a habit was firmly established – all without asking people a single question. This type of research also allows for much larger sample sizes too. There is also more advanced technology. Curtis and her colleague Bob Aunger have also been developing Real-Time-Location-System (RTLS) Monitors – a ‘smart home’ system that enables detection of behaviours in the home and other frequently visited places.

Technology in the form of smartphone apps may also be able to start observing behaviour unobtrusively and yet accurately too. Apps are increasingly capable of achieving all sorts of things – from measuring our exercise behaviour and sleep routines to being able to tell us whether we have anaemia, skin cancer or breathing problems. So the possibility of tracking and recording other behaviours – and even measuring automaticity - is not pie in the sky.

CONCLUSION

Thinking more deeply about the strength of habits or, put another way, the potential difficulty of achieving the behavioural change we desire, will allow us to look at a behavioural task with our eyes more wide open and will also deliver deeper behavioural insight. The framework around repetition, automaticity and identity empowers us with a meaningful architecture within which to explore habit loops and, with technology on our side, measurement will become more sensitive and more insightful, able to inform us more and more clearly whether we need to reach for the carrot, compose a sermon or look for a big stick!

You can read the full three-part report by downloading the pdf below.

Read more from Crawford.

[1] Allcott, H., Rogers, T. “The Short-Run and Long-Run Effects of Behavioral Interventions: Experimental Evidence from Energy Conservation” NBER Working Paper, October 2012

[2] DEFRA “Habits, Routines and Sustainable Lifestyles Summary Report: A research report completed for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs by AD Research & Analysis”, November 2011

[3] Bargh, J. A., “The four horsemen of automaticity: awareness, intention, efficiency and control in social cognition” In ‘Handbook of Social Cognition: Vol 1 basic processes’, pp1-40, 1994, Eds: RS Wyer & TK Skull.

[4] Verplanken, B., and Orbell, S., “Reflections on Past Behaviour: A Self-Report of Habit Strength” 2003 Journal of Applied Social Psychology 33, 6, pp. 1313-1330

[5] Gardner, B., Abraham, C., Lally, P., de Bruijn, G. “The Habitual Use of the Self-report Habit Index” Letter to the Editor of Ann Behav Medicine 2012, 43:141-142

[6] Verplanken et al 2003.

[7] Phillippa Lally and colleagues recently identified the point at which habits are established on average. Taking the simple habit of getting people to go for a walk after breakfast, they tracked automaticity to see when the post-breakfast walk became a habit. In this case, the habit was established after around 30-40 days. On average it takes around 2 months/ 66 days to form a new habit. See Lally et al 2009 and Gardner et al, 2011.

[8] Lally et al “How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world” 2009, European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998-1009

[9] See Lally et all 2009 and Gardner et al, 2011

[10] Gardner, B., Abraham, C., Lally, P., and de Bruijn, G.J., “Towards parsimony in habit measurement: Testing the convergent and predictive validity of an automaticity subscale of the Self-Report Habit Index” International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity 2012, 9:102

[11] Judah, G., et al “ Experimental Pretesting of Hand-Washing Interventions in a Natural Setting” Supplement 2, 2009, Vol 99, No. S2, American Journal of Public Health