It’s tough – people are naturally creatures of habit, can even be slaves to them - and habits are usually deeply embedded. Trying to unravel existing habits and getting people to change and do something new is one thing and can be a major mental battleground, trying to initiate a new habit or way of behaving from a standing start as it were, is something else entirely.

This article discusses creating new habits in depth and is Part Two of a three-part series. In Part One we examined the theory behind habit formation and the things we can do to put a stop to stickily engrained bad habits. In Part Two we focus on ways of creating new habits in our lives; Part Three will look at how we can measure habit strength through different sets of indicators and why measurement is useful.

There are numerous examples of initiatives and campaigns which have succeeded in altering attitudes and even intentions to change behaviour but which have often faltered at the final hurdle - that of behavioural change itself- especially when habits are strong and behaviour is deeply embedded. For example, an information campaign designed to reduce substance abuse actually increased use[1].

Over the last decade or so there have been breakthroughs in our understanding of habits, analysing our routines in micro detail for instance, in order to determine how habits are formed. Research has also looked at how to shape and change behaviour whether via the powerful influence of contextual changes, or using an existing habit to trigger another, or creating a psychological or even tangible reward for a new behaviour.

In this article we look at some of this research, in particular that which deals with forming new habits. The magic number three would seem to be key if we want to learn and engender a new behaviour - so here are three steps to habit formation:

Step 1) Choose a new habit or behavioural goal and focus on it

Pick a particular behaviour you want to add to your life and make a habit of. Or, from the perspective of a marketer or policymaker, decide on the particular behaviour change you want to instil in others.

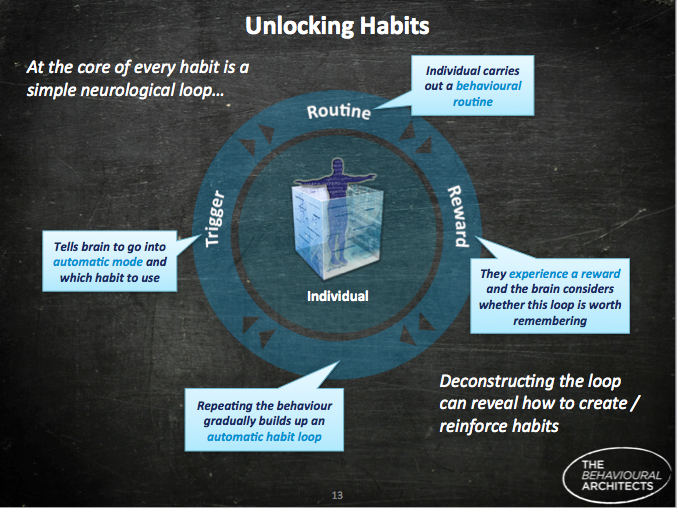

With a particular new behaviour (habit) in mind, the next two steps are based around a very simple model to promote repetition of the behaviour. When thinking about behavioural change it is critical to consider the whole picture, and to be particularly conscious of what's been termed the habit loop[2]. It's easy to do something differently just one time, but hard to incorporate that behaviour change long term. This model forces us to think about the neurological loop at the base of a habit. Habits are built through context-dependent repetition so identifying the triggers (or cues) and the rewards for a new habit will help to build that repetition and create a habit loop by developing automaticity – a key feature of any habit. Some even believe automaticity is the essential feature. Both the repetition and reward steps are equally important so it’s essential to consider both.

As behavioural experts Bas Verplanken and Henrik Aarts state, habits are “learned sequences of acts that have become automatic responses to specific cues, and are functional in obtaining certain goals or end states.”[3]

Source: Based on Charles Duhigg's 'Habit Loop', ‘The Power of Habit’, Random House, 2012

Step 2) Identify the behavioural cue or trigger which will drive your new habit

Habits are triggered by the context we are in and the circumstances which cue the particular behaviour. So when you're looking to engender a new habit, it can help to analyse and identify the possible existing contextual triggers or potential cues to facilitate this. A useful rule of thumb is to consider what prompts us to do certain things - ‘if Trigger X happens, then we do Behaviour Y’. Triggers do not always need to be blatantly obvious, they can be subtle too – the key thing is that you are aware of them, even if only subconsciously.[4]

Triggers fall into five primary context types[5]:

- Location - where we are

- Time - what time of day or year it is

- Other People - who we're with, and what other people around us are doing

- Emotional State - how we feel, what mood we're in

- Immediately preceding action - what we've just been doing

Connecting new behaviours to existing behaviours – a concept known as ‘piggybacking’ is a strategic approach to new habit formation. For example, Febreze, the air freshener from P&G was successfully marketed to consumers as the reward at the end of a cleaning routine – the finishing touch if you like – so it became a habit which was initially piggybacked onto the end of a cleaning routine and gradually became the inextricable reward part of the routine itself. Suntory, the Japanese whisky group, started to serve the humble Whisky-Soda in pint glasses, in order to piggyback the drinking experience onto well-established beer drinking behaviours. This drink format – dubbed the “highball” – has helped sales of whisky in Japan to rise by 10% a year over the past three years. So it's wise to look at existing routines and work out if a new habit can be added to an existing one.

As B J Fogg of Stanford University's Persuasive Technology Lab is fond of pointing out, it also helps if you make new habit building easy and piggybacking or paralleling one habit onto or alongside another are good ways of doing this. So if you're trying to introduce a new habit it makes sense to lean on an existing behaviour and try not to overreach yourself. One of Fogg's own practices, based on his 'Tiny Steps' approach, is described by him here and it shows how you can parallel a new behaviour with an existing one:

“One practical habit is, as soon as the phone rings, I put on my headset and I start walking. This has grown to lifting kettlebells or doing little one-leg squats while I’m on the phone. The desired behavior is to be active and working out in these small ways. I’m on the phone two to three hours a day, and now it’s a habit that I probably can’t stop. When I take calls, I’m up and walking around. I’ve created all these tiny habits in my life, from really practical to kind of crazy.”

He describes the genesis of a piggybacking/tiny steps habit which began with a simple intention to do two push ups each time he used the bathroom[6]. The push up habit not only became routine, it evolved into a full blown work out with Fogg routinely hitting 100 push ups. As a result of a tiny habit, hitched to a very routine behaviour, a consolidated, committed practice was born - and the reward? Fogg lost weight and gained stamina. A possible mantra for instilling the piggybacking habit could be 'After I ..... ‘ or ‘When I ….’[insert routine behaviour], ‘I will ...... [insert new habit to engender]'.

Step 3) The Power of Tangible, Subconscious and Biological Rewards in Building a Habit Loop

In almost all habitual behaviours we can identify a reward element that gives the habit its addictive appeal. Since we know that the reward is the bit that fixes the habit in place it makes sense to set up the reward structure if we're aiming to engender a new habit. Creating an incentive or reward will help to motivate and encourage us to carry out a particular behaviour, and a reward is especially important if the new habit we want to engender might seem difficult or time consuming. A reward might even exist already – we simply need to make it more overt and appreciated. Secondly and crucially, it can help to reinforce the routine and make sure we keep on repeating the new habit, eventually making it automatic. The type of reward can be tangible, e.g. a treat after a work, or more subconscious - perhaps just feeling good about yourself:

A reward might even exist already – we simply need to make it more overt and appreciated. Secondly and crucially, it can help to reinforce the routine and make sure we keep on repeating the new habit, eventually making it automatic. The type of reward can be tangible, e.g. a treat after a work, or more subconscious - perhaps just feeling good about yourself:

- Tangible rewards: A simple example might be cycling into work and picking up an espresso from your favourite coffee shop once you've parked your bike. Or the reward can retrospectively drive the behaviour - going to the gym might mean you feel justified in eating dessert with dinner. A study on travel habits found that free bus passes in Stuttgart helped to create a new habit of using public transport among people who had recently moved to the city. Use of public transport rose dramatically from 18% to 47%.[7] In this case, the reward of free bus travel might actually be the main driver behind the habit. A tangible reward could also be getting closer to or actually achieving a goal, so keeping a written record of smoking free days, or laps swum in the pool, or kilometres run can be a strong motivator.

- Subconscious rewards: A reward can be less tangible – perhaps a feel good sense of belonging among colleagues at the pub, or a self-esteem boost from a shopping spree. It could also be a sense of progress at the end of the day on a project at work. TBA recently carried out some consumer research on kitchen surface cleaners amongst housewives in Asia and discovered that the hidden reward for using a new, better product was actually a social reward and sense of empowerment; the new surface cleaner took the place of a quick once over with some washing up water and created a clean smelling environment, as a result, friends and family of the housewives who had used the cleaning product found the newly cleaned and aromatic kitchen a more pleasant place to be and so were more likely to congregate in the kitchen after dinner. The reward for the housewives was less social isolation and more family interaction.

- Pleasure-based, physiological or biological rewards: Some enjoyable behaviours prompt your brain to release the feel-good chemical dopamine. This is often used to explain ‘runner’s high’, and it is known to contribute to drug or gambling addictions. Food, and comfort-eating in particular, can also provide a psychological reward and smoking delivers a nicotine based reward.

These different types of rewards may not be mutually exclusive either – they can be layered, or there can often be a short term tangible reward combined with a longer term goal. For example, brushing your teeth rewards you with a tangible, clean, minty fresh sensation in your mouth, but also rewards you with healthy, white teeth throughout your lifetime – and fewer fillings…

BEHAVIOURAL STRATEGIES WHICH HELP TO PROMOTE REPETITION

Although creating triggers and identifying or building in a reward for a new habit are certainly the backbone of bedding down a new habit, there are a number of additional strategies or opportunities to consider which can help to build repetition and strengthen the automaticity of a habit. Here are four to think about:

- Commit to a plan: New habits don’t just happen. We need consciously to work out how to build them into our lives. One technique is to make an exact plan. A study which looked at people trying to create a new habit of daily flossing found that those participants who first outlined when and where they would floss each day, flossed more frequently over the four week intervention period than those who did not.[8] By thinking things through, you are working out your triggers, in this case being in the bathroom, and by stating what you will do - flossing every day - you are committing yourself more firmly to actually doing it. Behavioural scientists call this commitment bias - we are more likely to carry out a task if we commit to it, especially publically. Where the habits you want to engender are likely to take place at home, it would help if you were to announce to family members exactly what you plan to do. (Other forms of commitment bias might involve teaming up with another person because it makes you responsible to them; for instance a jogging partner or a fellow smoker you make a pact to quit with.)

Making a plan might also involve the breaking down and removal of any barriers to forming new habits. For example, a barrier to commuting to work by bike might be poor knowledge of cycle routes.[9] So investing a few hours to read a cycle map, or even practice or experiment with routes on a quiet Sunday morning when you are not in a rush could help to break down those barriers.

- Make a small change or addition to a stable context: Much of our context and the routines we follow are fixed partly because we tend to prefer routine and automatically seek it out. Our lives are for the most part, constructed of deeply embedded routines - researchers have demonstrated that as much as 45% of our daily actions are habitual – so you need to be clever to make any lasting changes to your routines. One useful approach is to build new habits within your existing stable context so that behavioural patterns will more easily establish themselves, because the same trigger(s) are there every time – every day, every week.

A project to improve water sanitation in Kenya needed to get villagers to chlorinate their water. Poor water sanitation is a major cause of illness in developing countries and using chlorine tablets is a simple and effective way of purifying water. However, despite the availability of free tablets, people were not using them, largely  because they were not in the habit of using them. The research team knew that the villagers collected water every day so they designed and installed chlorine dispensers at the point of water collection (see image). They also made the default amount of chlorine dispensed match the standard size of container the villagers carried making it easy and simple to use.[10]

because they were not in the habit of using them. The research team knew that the villagers collected water every day so they designed and installed chlorine dispensers at the point of water collection (see image). They also made the default amount of chlorine dispensed match the standard size of container the villagers carried making it easy and simple to use.[10]

When people have lives where contexts are fluid and less predictable, it can be harder to form new habits since the contextual trigger may not always be present. If working patterns are very changeable in terms of time or location or both, people face bigger barriers for developing desired habits and routines. In the same way holidays, business travel and even weekends can often disrupt the embedding of new habits because they change the context so completely. A study which followed adults enrolled on a weight loss intervention programme found that although people were able to begin developing healthy habits in the workplace during the week, these new patterns of behaviour were often disrupted at weekends and during holidays: One participant said “Weekend evenings have been a bit of an issue over the eight-week programme because you go out or get invited out for a meal with friends and you all have a drink and la la la!” Another participant said “My last two weeks have been a bit of a disappointment …I was on holiday and it was takeaways every night…But since I’ve been back from holiday I’ve gone straight back to it.”[11]

For those with varied, frenetic and unpredictable weekdays at work, weekends may be a better opportunity to build habits since they may be more in control and in a stable context at home.

- Take advantage of major permanent disruptions: A major, permanent life change provides one of the easiest, natural opportunities to create new habits since it disrupts existing routines so completely, changing the context and providing a new space to replace with new habits. It might be a permanent change in your environment; a new life-stage, moving house to a new location or beginning a new career. On average, Americans move every five years[12] – so every five years, provides a perfect opportunity to change your habits - if you live in the States. David Halpern of the Behavioural Insight Team in the UK says that successful behaviour change is sometimes “… about intervening at the right time. If you contact people within three months of them moving into a new house, it’s highly effective – because behavioural patterns haven’t re-established themselves yet.”[13] Evidence suggests this type of context change can be effective because it shakes up the status quo before allowing it to settle, and in the settling process new patterns can be shaped. One study asked participants to write an account of a successful or failed life change experience. In analysing each of these stories, researchers found that 36% of accounts of successful behaviour change involved moving to a new location, whereas only 13% of accounts of unsuccessful attempts involved moving. 13% of successful behaviour change also involved altering the immediate environment, whereas unsuccessful behaviour change was always characterised by no changes in environmental cues.[14] So if you're about to make a big change think about making some new habits while you're at it.

- Practice makes habit: It takes time to build a new habit, embed it in our routines and make it automatic. Realistically, no new behaviour is going to become part of your life overnight. A study conducted by Phillippa Lally and colleagues at the Health Behaviour Research Centre at UCL in 2009 found that it took anywhere between 18 days (2.5 weeks) and 254 days (over 8 months) to cement a new habit. The average was 66 days.[15] And these were pretty simple new behaviours such as eating a piece of fruit with lunch or drinking a glass of water after breakfast. Moreover, if you are changing a habit, rather than adding a new one, your brain will never forget the old habit – the same neurological loops are still there - and the old behaviour will come creeping back very easily if you let it. So to build a new habit, it is necessary to keep on doing it – for many days - until it becomes automatic.

CONCLUSION

When you think about building new behavioural habits think about how to identify the right contextual triggers [and remember that contextual triggers can come in all shapes and sizes]. Then think about the importance of the reward or reward mix from overt to deeper psychological rewards. And together with the actual desired behaviour conceptualise the habit goal as a behavioural loop with clear structural foundations and suddenly it will seem more achievable. But also remember cementing a habit takes time - it can take on average two months to build a new habit, to form and ingrain that neurological loop - so perseverance is all.

As for me, I am off to finish my habitual post article completion push-ups. 88, 89, 90…..

You can read the full three-part report by downloading the pdf below.

Read more from Crawford.

[1] Derzon, J.H. and Lipsey, M.W. “A Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Mass-Communication for Changing Substance-Use Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviour” (2002) in Mass Media and Drug Prevention: Classic and Contemporary Theories and Research, W.D. Crano and M. Burgeon, eds. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 231-58

[2] We'll credit Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit, with the term habit loop

[3] Verplanken, B., Aarts, H., 1999

[4] The change in context must be perceived and noticeable. Some people with very strong habits might fail to notice small changes in their environment. For example an affirmed car commuter might not necessarily consider cycling to work even when the road they usually use to commute introduces a specially designated cycle lane. In the same way adding an ‘eco-wash’ setting to a new brand of washing machine might not be enough of a context change to nudge people into choosing a washing program with a more environmentally friendly setting.

[5] For example, see Verplanken, B. and Wood, W., “Interventions to Break and Create Consumer Habits” Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, Vol 25(1) Spring 2006, 90-103

[6] "After I pee, I do push ups" BJ Fogg

[7] Bamberg, S., “Is residential relocation a good opportunity to change people’s travel behavior? Results from a theory-driven intervention study.” Environment and Behaviour 2006 38:820

[8] Orbell, S., and Verplanken, B. “Implementation Intentions Can Enhance Habit Formation” (2006)

[9] http://www.cyclescheme.co.uk/community/how-to/10-ways-to-encourage-colleagues-to-cycle-to-work

[10] www.povertyactionlab.org/scale-ups/chlorine-dispensers-safe-water

[11] Lally, P., Wardle, J. and Gardner, B., “Experiences of habit formation: A qualitative study” Psychology, Health and Medicine: Vol. 16, No. 4 August 2011, 484-489

[12] Jasper, J.M. (2000) “Restless Nation: Starting over in America” Chicago: University of Chicago Press

[13] The Daily Telegraph, 11th Feb 2013: www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/9853384/Inside-the-Coalitions-controversial-Nudge-Unit.html

[14] Heatherton, T.F., and Nichols, P.A., “Personal accounts of successful versus failed attempts at life change” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1994, 20, 664-675

[15] “How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world” by P Lally, Chm Van Jaarsveld, Huw Potts, J Wardle, European Journal of Social Psychology (2010), Volume: 1009, Issue: June 2009, Publisher: JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD, Pages: 998-1009