Earlier this month I did a webinar for the lovely people at the World Advertising Research Council about attention, rounding out a half year of touring my book Paid Attention, which has seen the talk I give evolve considerably, as the conversations have evolved around attention and ad blocking.

You can watch it on the site [it says it's a download but it's not, it goes through to a streaming screen] and I thought I'd pull out one new element I've been thinking about: the axes of attention.

In my book I suggest attention is a resource, and it is traded through what is a kind of derivative or proxy or possibility point called the impression. Since impressions are binary, on or off, they make us think of attention that way, even though we know it isn't.

Microsoft did some very famous research this year which was reported as

"Humans have shorter attention span than goldfish, thanks to smartphones"

and got a lot of press because it feels like something that is true, that our spans of attention have decreased, that it's harder to focus, because Internet.

However, this sort of research is somewhat spurious because there is no agreed definition of "attention spans" and because Microsoft created it to sell certain kinds of advertising units - short ones, one assume.

[Always look to the source of an article or research, because all content is advertising something.]

Here is the primary research so you can look at it - it has lots of interesting depth to it, but we always look for the super simple "insight" even in areas that are amazing complex, like cognitive research. We are biased towards simplicity because we only ever encounter complexity in the real world.

Hence, stories and myth and how memory works and the oft spouted belief in simplicity, which often masks or distorts instead of reflecting reality.

Anyway, the major point, made by Microsoft CEO is one I, obviously agree with, hence my book:

So we live in a world with many more options and distractions, and so we can't focus as much, because they are always alternatives.

Every tiny bit of our attention takes something from us, and we have a limited about of time and cognitive resources each day.

We trade our attention for content - that's how advertising mostly works -

except for with billboards, which is why David Ogilvy hated them, because there is no consent, no value transferred to the individual.

and because attention is much more limited than content now, the price should go up. But the market has incorrectly priced attention because impressions are not quite the same thing.

So you can understand ad blocking, or TIVO, as the market trying to correct the price of attention.

The attention cost in advertising of an episode of television on broadcast channels feels too high - too many breaks, too many ads, too high a frequency. Hence the practice of recording shows you watch live [one the rare occasions on you do] and starting 2o minutes later to skip past the breaks.

Adblocking is the same - the price we started to have to pay in attention terms for the content no longer felt right, the price was too high.

And, like in the tragedy of the commons, when too many bites of the pie are taken, the resource collapses. They take away our access to their attention, as also happened with billboards in Sao Paulo and Chenai. They became too numerous, too intrusive, and then they were banned. Attention collapse can happen.

That said, somethings are very good at holding our attention.

To give the most extreme example, a man in Taiwan died this year after a 3 day gaming binge. Video games are extremely good at holding attention for very long periods. I don't think World of Warcraft players spending hours or days playing feel like they have short attention spans in that moment.

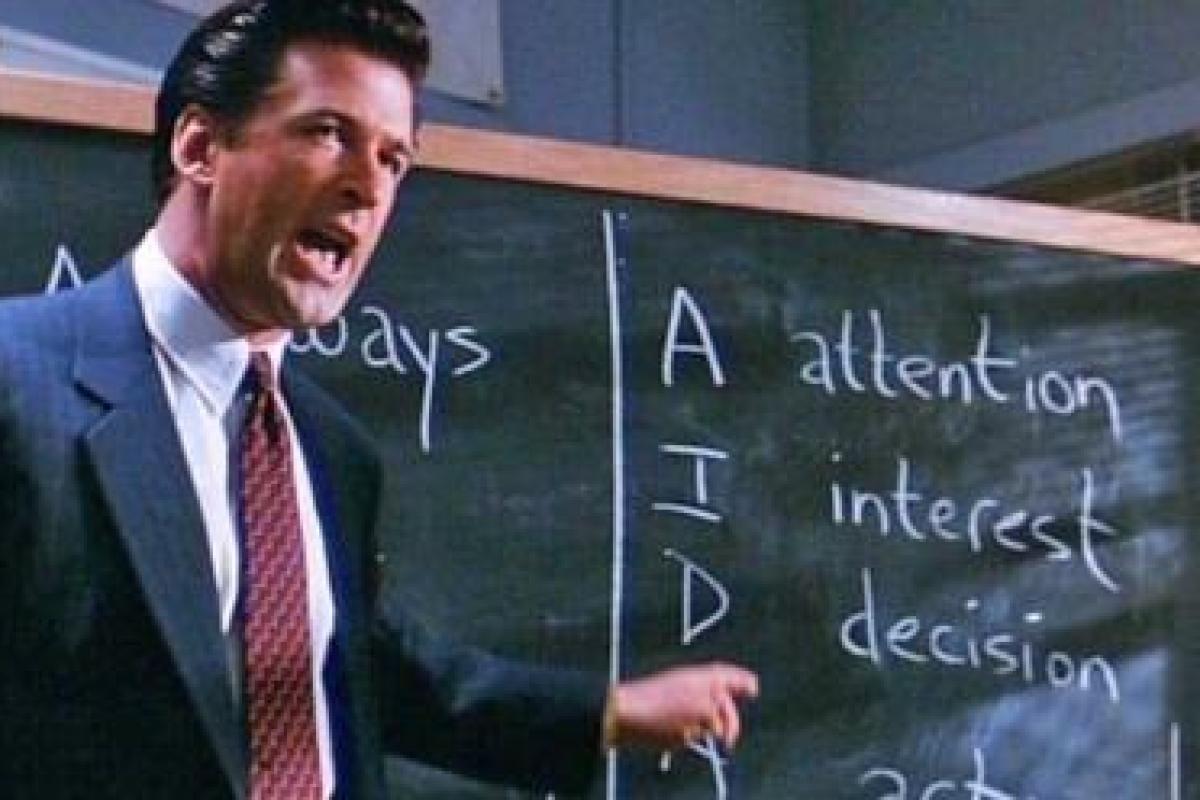

So, a more varied understanding of attention is needed. It has 2 axes, not just one: duration and intensity, as in the chart at the top.

Paul Feldwick reviewed my book [which is awesome and I'm super grateful about] and pointed out that:

"So – to take a significant example – although there’s a great deal about the importance of ‘low-attention processing’ and frequent acknowledgement that advertising works in complex ways, the theme of ‘attention’ as flagged in the title keeps popping up without qualification as if it were always essential."

And I'd argue that it is, in the sense of duration.

Advertising can work with "low attention" - low intensity - as Professor Heath has well established. But it cannot function with no duration at all, that's just logic, simply because it means you never saw it, at all, anywhere, even in your peripheral vision.

Here we get into a tricky area because "conscious attention" and perception aren't the same thing exactly, inattentional blindness exists for example, which means we may not see things we aren't paying attention to even if we look at them, on the one hand, and you may never pay much conscious attention to a poster or TV spot as you see them.

So, for posters, low attention processing may happen well below your conscious threshold, but that can't function when you have adblockers online, because the ads never get in front of any sensory organs.

All of which is perhaps to say that communications need an attention strategy, to understand the attentional quality it is attempting to use in context, to appropriately value the attention is consumes from people, to balance out the attention debts people are feeling, to restore balance to the force.

[Go watch the webinar over at WARC, which features attention hacks and various other nuggets of stolen genius]

---

So, that wraps my year of thinking about attention with a rare but fun rant, to quote Tim Minchin.

I'm going to triple post this to Medium and Linkedin as a little experiment.

We are going offline for a bit to think about something new.

Happy New Year!