How small changes in this architecture can radically impact our decisions

Throughout our day, we might like to think that we make rational, conscious choices – for example, about what to eat, how to analyse a problem at work, what we choose to read, what new phone to buy. In reality though, our choices and decision-making are often influenced by choice architecture – tiny, subconscious effects derived from the context in which we make the choice. Things such as what we anchor to and use as a reference point, what prices or product qualities seem most salient, what order the choices appear in and how many options there are to choose from can all ultimately impact on our decision.

We are also not homogeneous consumers, and we each respond in different ways to different types of choice architecture depending on (amongst other things) how numerate we are, our age and possibly our background and culture.

For us as marketers, a deeper understanding of both these subconscious effects and cues – what we call ‘choice architecture tools’ – and differences among consumers, can empower us to steer people toward the choice we'd like them to make, or the best choice to help consumers to feel more satisfied with their choice. Below we consider some of the main tools we can use as choice architects.

Navigating choice via extremes

When making a choice, we are often affected by the context in which we make that choice and the other options available. We anchor to extremes and tend to pick the middle one as a compromise.

In one experiment researchers found that introducing a third option changed preferences considerably. One group was given a choice between two cameras - a $170 Minolta camera and a better Minolta, priced at $240. People’s preferences were split evenly, at 50% each. A second group was given a choice between three cameras – the two described above and a third, high quality Minolta, priced at $470. Introducing a third option led to a much higher preference for the now middle option – 57% preferred the $240 camera and preferences for the two extremes were split evenly at 22% and 21%.[1]

The researchers – who term this phenomenon ‘Extremeness aversion’ – explain it in part through the way we analyse advantages and disadvantages. Loss aversion, a well known behavioural economics concept, tells us that we dislike losses more than we enjoy similar gains. So the disadvantages of the lower extreme – in this case the relatively poor quality of the $170 camera in comparison to the middle option – seem more salient than the relative gains of the high quality Minolta. The $470 camera seems less appealing since we value the gains less, but we feel the losses more when opting for the $170 camera. So we often settle for the middle option.

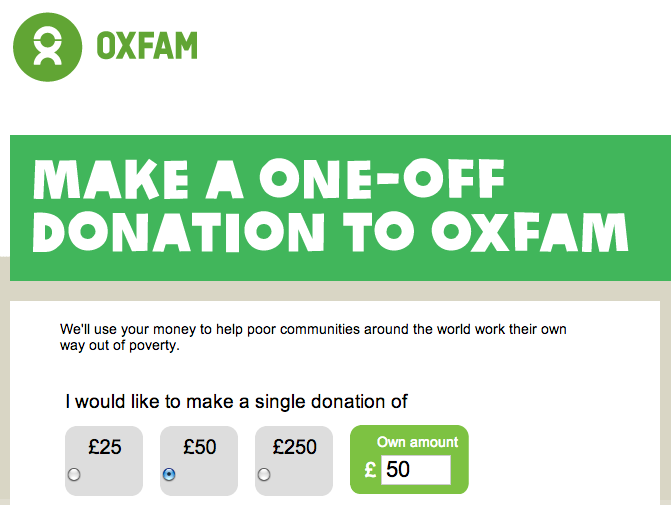

Companies and organisations often use this to good effect. For example, the charity Oxfam present three pre-set options for people who want to make a one-off donation. It changes from year to year – currently it is set at £25, £50 or £250 on their website.[2] £250 probably seems a bit high for the average person, even for a one-off donation, but £25 feels quite low. So we opt for the middle option of £50. In comparison to £250, £50 doesn’t seem like too much of a step up from £25. (The Oxfam website also pre-selects the middle option as the default and the suggested ‘own amount’ – see image below)

Highlighting a trade-off

Another way in which we are influenced by context is when trade-offs appear more salient than others. So the same product may seem more appealing when presented together with less attractive products and less appealing when presented with more attractive products. For example, in weighing a trade-off between two attributes – perhaps deciding whether the price difference outweighs the quality difference for two products – consumers are likely to be affected by the existence of a third product.

For example, one study presented consumers with options for microwaves. One group was asked to choose between a cheap Emerson microwave priced at $110 and a better quality Panasonic one priced at $180. However, these were discounted prices with a third off. In this group 57% chose the cheaper Emerson model and 43% chose the Panasonic.

A second group was presented with three choices, the two microwaves described above, with a third option of a $200 Panasonic whose price had only been discounted by 10%. Due to the discounts, the $180 Panasonic now looks like a good choice, based on quality. And the consumers in the second group thought so too with 60% now choosing the $180 model, only 13% choosing the $200 model and just 27% now choosing the Emerson model.[3]

Beyond the obvious implications for the context in which choices are presented, designers and marketers could also consider the implications for new product development. Not only can we consider the absolute qualities of the new product, but also its relative predicted position in the market in price and quality and how it might be ranked – both against competitor brand ranges, but also within the range of its own brand. Extremeness aversion suggests that the introduction of a middle option will hurt the low price-low quality extreme more than the high price-high quality extreme.

Three or five may not necessarily be magic numbers

With the fact that we tend to go for the middle option in mind, it is also important to think about how many options we present to people in any context, such as in research or in business decisions, and not just to consumers in a purchase environment. If we want people to gravitate to the middle option then 3 or 5 might well be the best option but if we want them to think a little harder, maybe engage their system 2 a little more , then we need to think more carefully about the options we present.

Pierre Wack, one of the pioneers of scenario testing in business, noted that presenting managers with a choice of three scenarios often results in managers picking the middle scenario because they see it as a compromise or baseline scenario compared to the first and third options. These tend to be seen as extremes and therefore (in their view) less likely to occur:

"A design that includes three scenarios describing alternative outcomes along a single dimension is dangerous because many managers cannot resist the temptation to identify the middle scenario as a baseline. A scheme based on two scenarios raises a similar risk if one is easily seen as optimistic and the other pessimistic. Managers then intuitively believe that reality must be somewhere in between. They "split the difference" to arrive at an answer not very different from a single-line forecast."[4]

The recommended number of scenarios is actually four – not so many choices that we are overwhelmed, and giving us no ability to select a middle option.

The subconscious influence of order

Not only is context important, but the order in which choices are presented can also be influential. For example, a recent study by The Kings Fund looked at the order in which hospital choices were presented to patients and found that when hospitals were listed by quality, highest quality first, patients actually tended to choose the fourth option (out of a list of five) and only 37% chose the highest quality hospital (which actually fell to 34% when they were given more information about each choice). Being first on the list is not necessarily best. When hospitals were sorted by distance, the proportion choosing the highest quality hospital rose to 48% and as high as 58% when more information was provided. The researchers hypothesise that these differences occur because people ‘over-search’ when the cost and effort of searching is reduced for us in the way the information is presented and framed, almost as if we don’t trust the filtering that has already been done for us. They also speculate that we are naturally drawn to the centre of the screen – the middle option – avoiding extremes.[5]

Conclusion

This range of examples illustrates just how much choice can be influenced or guided in different ways using a variety of tools. And, like it or not, it is nigh on impossible to present a choice in a wholly neutral way. As Professor Neil Stewart at Warwick Business School once commented, 'you’ve got to put the products on the shelf in some order' and whatever you do, because of the way we process different cues, one option or another will always be more appealing.[6]

Further, just as choice architecture varies, so too do consumers and the ways in which they are affected by choice architecture – and we need to take that into account as choice architects. Eric Johnson and his colleagues argue that:

“…choice architects will have to design decision environments […] with knowledge about the characteristics of targeting decision-makers and how they will process and draw meaning from the information, or what their goals are.”[7]

For example, some consumers are more numerate than others, whilst some research has suggested that older consumers prefer less choice or more simplified choice than younger consumers. And we probably all pick up on different cues depending on both long-term experience and how we have been subconsciously primed by our immediate past experiences or what emotional mood we are in.

At The Behavioural Architects we believe that designing the most appropriate choice architecture and applying some of these powerful tools to steer people in the direction required, needs to be carefully informed by an in-depth understanding of the unique conscious and subconscious behavioural drivers: understanding the behavioural architecture inspires the choice architecture.

Read more from Crawford Hollingworth.

[1] Simonson, I., Tversky, A. “Choice in context: Tradeoff Contrast and Extremeness aversion” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 29, No. 3, 1992

[2] https://donate.oxfam.org.uk/Give1

[3] Simonson, I., Tversky, A. “Choice in context: Tradeoff Contrast and Extremeness aversion” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 29, No. 3, 1992

[4] Wack, P. “Scenarios: Shooting the rapids”, 1985, Harvard Business Review

[5] Reutskaja, E., and Fasolo, B. “It’s not necessarily best to be first.” Harvard Business Review 2013 and Boyce et al “Choosing a high-quality hospital” The Kings Fund 2010

[6] BBC Radio 4 ‘All in the mind’ 1st November 2011

[7] Johnson et al, ‘Beyond Nudges: Tools of choice architecture’, Published online May 2012, p497