‘Ashes’ still from film - Steve McQueen

‘The fact of the matter is I’m interested in a truth. I cannot put a filter on life. It’s about not blinking.’

Steve McQueen

I recently visited the excellent Steve McQueen exhibition at Tate Modern (until 6 September 2020).

We’re greeted by the Statue of Liberty. She is filmed from a circling helicopter, and beyond her there are factories, warehouses and skyscrapers; bridges, barges and cruise ships - arrayed across New York Harbor, glistening in the sunlight. And yet she looks grim-faced, tired perhaps from holding her golden torch aloft for so long. Her garments of oxidised copper, in places caked in guano, seem somewhat tatty. The Dream she represents has achieved so much for so many. But now it is frayed around the edges.

We enter a room with a screen scrolling through old FBI files. They detail the surveillance carried out in the ‘40s and ‘50s on the singer, actor and Civil Rights campaigner Paul Robeson. Trivial observations and banal insights. Heavy type and crude redaction. A voiceover reads from another set of similar documents. We are immersed in a world of paranoia and anxiety; of secrecy and bureaucracy. The wary speculation of suspicious minds. The film runs for over 5 hours.

McQueen asks us to stay a little longer, to reflect on what’s going on around us - the mysteries, curiosities and injustices; the political intrigues and personal tragedies; the unvarnished truth. Stop, look and listen.

‘7th November’ - Single 35mm slide, sound, 23 minutes. Steve McQueen

'As far as I’m concerned, it’s all about the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. End of. To get to that, you have to go in close, uncover what’s been hidden or covered over. Obviously, the easy thing is not to go there, but I have a need to go there.’

McQueen takes us by the hand through the world’s deepest goldmine, the Tau Tona in South Africa. We encounter Tricky immersed in a recording studio. We reflect on the images NASA selected in 1977 to represent the human condition to possible alien life forms. We pause to examine McQueen’s nipple, Charlotte Rampling’s eye.

Here’s a young man named Ashes, sitting on the prow of a boat in Grenada, where McQueen’s father was raised. Ashes looks fit, handsome, self-assured - completely at ease with the blissful, open-skied world around him. We pause for a while and take in the azure beauty of it all. There’s a curious scraping sound - metal on stone perhaps? - coming from the other side of the room. We realise the large screen we’ve been watching is double-sided. On the reverse there are two workmen preparing a grave. It is Ashes’ tomb. The seemingly carefree young man got caught up in a drugs incident. Memento mori.

Born in 1969, McQueen grew up in Shepherd’s Bush and Ealing, West London. He was an undiagnosed dyslexic, relegated to the lower stream at school, and he had to wear a patch to cover a ‘lazy eye.’ He felt isolated.

'What I do as an artist is, I think, to do with my own life experience. I came of age in a school which was a microcosm of the world around me. One day, you’re together as a group, the next, you are split up by people who think certain people are better than you.’

Steve McQueen. (Photo: Thierry Bal)

McQueen studied art and design at Chelsea College of Arts and then fine art at Goldsmiths College. Increasingly he specialised in short films, and in 1999 he won the Turner Prize. In 2006, commissioned to visit Iraq as an official war artist, he commemorated the deaths of British soldiers by presenting their portraits as sheets of stamps.

Since 2008 McQueen has created feature films. ‘Hunger’, ‘Shame’, and ‘12 Years a Slave’ considered an Irish hunger strike, sex addiction and slavery. With ‘12 Years a Slave’ he became the first black director to win a Best Picture Oscar.

For McQueen close scrutiny of the world frees us from the indifference and detachment of our comfortably numb, accelerated modern lives.

‘You want to cause a bit of trouble, stir things up a bit. We’re all a bit numb right now, so that’s even more important. It’s like, ‘Wake up! Wake up!’ Let’s make some noise.'

McQueen makes the point that the better we see - the more we bear witness - the more we are seen.

'It’s not just about anger. It’s about seeing, contemplating, serious consideration. It’s about being seen, and heard and recognised, so as the years pass they can’t make you invisible.'

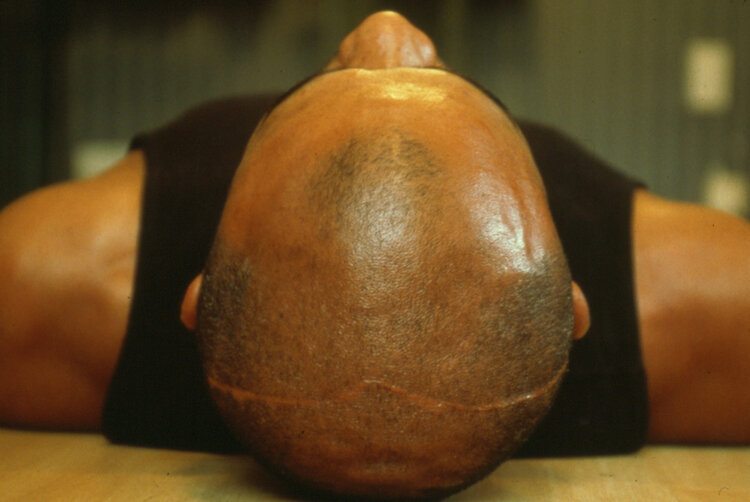

We encounter Marcus, McQueen’s cousin, lying with his close-cropped scalp facing towards us. A scar runs from one end of his head to the other. Marcus relates the chilling story of how he shot his younger brother. A small mistake leads to another bigger mistake. And so, in an instant, one life is ended and another changes forever.

'Easy, Natty, easy.

Nah take it so rough.

Easy, Natty, easy.

Babylon too tough.

Them a walk, them a shoot, them a loot.

Babylon them a brute.

Them a walk, them a loot, them a shoot.

But we know evil by the root.’

Gregory Isaacs, ‘Babylon Too Rough’ (G Isaacs / W G Holness)

This piece first appeared on Jim's blog here.