I recently attended an exhibition of the work of Swiss artist Felix Vallotton. (The Royal Academy, London, until 29 September, and then the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 29 October to 26 January.)

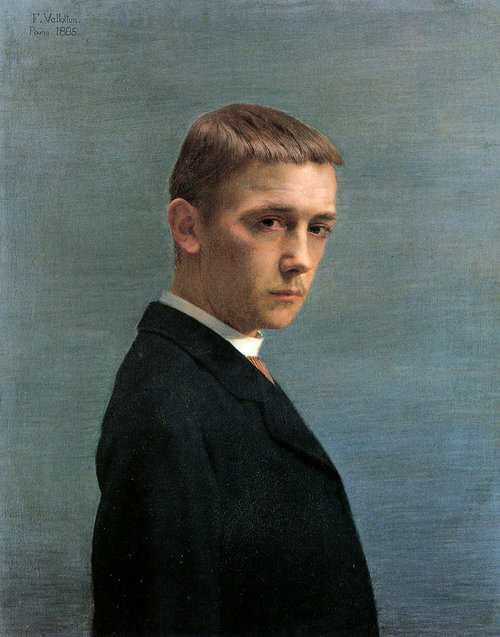

Vallotton was born into a puritanical protestant family in Lausanne in 1865. Aged 16 he settled in Paris, at first to study and then to practice art. In the 1890s he associated with the circle of artists known as the Nabis (Prophets), whose number included Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard. They sought to convey emotion rather than just to record reality. They admired Japanese woodblock prints, and their work was characterised by flattened figures, strong outlines and bold colours; by empty spaces and decorative patterns.

Vallotton became a master of the art of woodcut and he was commissioned to produce illustrations for journals and newspapers, including the influential La Revue Blanche.

Belle Epoque Paris was prosperous and dynamic, brimming with fashion, fun and creativity. It was the centre of the art world and a hub for scientific innovation. But it was also a hotbed of political unrest and social upheaval. Vallotton seems to have been both captivated by the capital’s boundless energy and conscious of the tensions that lay just beneath the surface. In his work he regarded French society with an amused but critical eye, satirising the customs and values of the bourgeoisie.

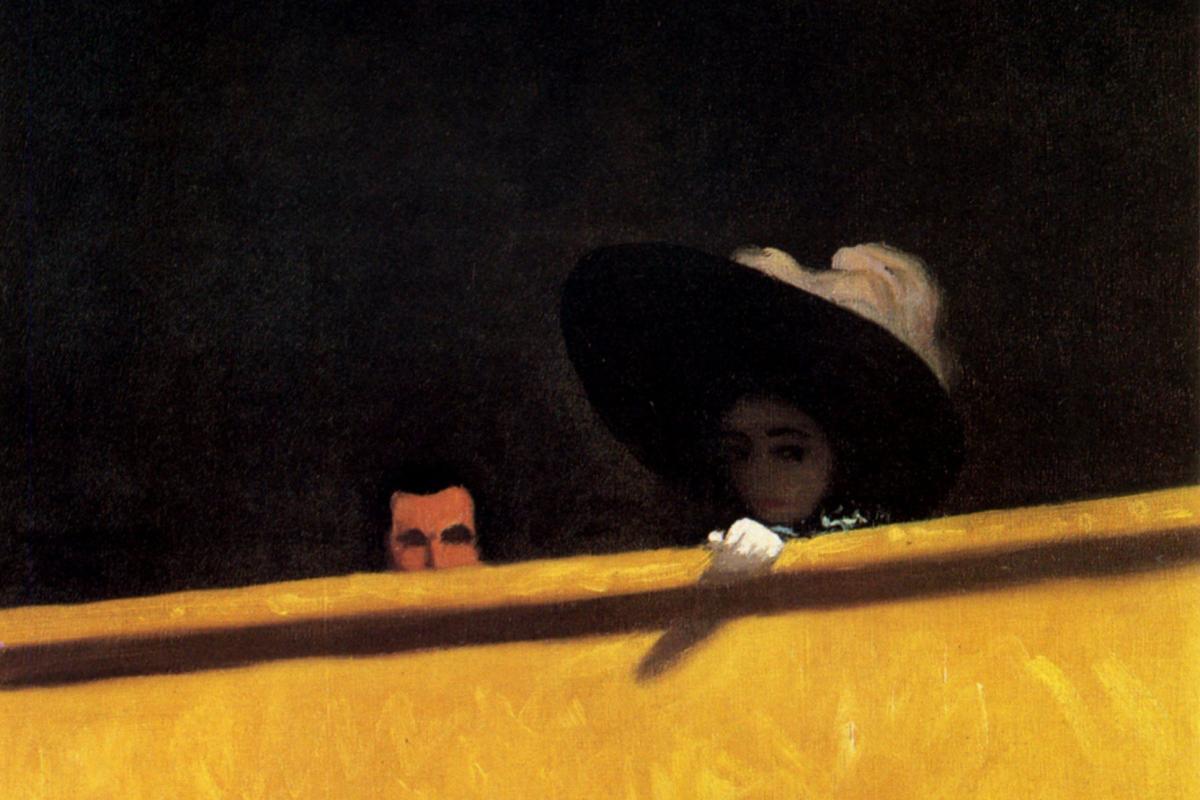

There’s a pervasive disquiet about Vallotton’s art. He seems uneasy about the relationships that are played out in the dim lamplight, in the shadows, behind closed doors; uneasy about the turbulence of city life, about the passions of the new consumer society, about the durability of the family unit. What hypocrisy remains unvoiced behind a conventional conservative façade? What secrets and lies lurk around the corner, along the corridor, or beneath the brim of an elegant hat?

They’re caressing fabrics at Le Bon Marche. They’re partying in the Latin Quarter. They’re rioting on the streets. The crowd runs for cover from the pouring rain. A smart-suited gentleman waits expectantly by the window. A desolate man weeps into his handkerchief as a woman looks impassively on. A couple embrace by the doorway to a claustrophobic interior. A darkness creeps across the pond in the garden. There’s a child chasing an orange ball, unaware of the looming shadows. There’s something missing in the linen closet. There’s a knife erect in the fruit loaf.

Everything seems slightly on edge, an intriguing, incomplete narrative, a pressure cooker about to explode. Vallotton ratchets up the tension with his terse, enigmatic titles: ‘The Lie,’ ‘The Money,’ ‘The Provincial,’ ‘The Extreme Measure.’ His work foreshadows Hopper and Hitchcock in its dark humour and unsettling air of menace.

Ours is an industry of emotions and enthusiasms; of fashions and fads. So it serves us well to retain a healthy objectivity, a suspicion of success, a caution around modish ideas. Scepticism insures us against egotism. Paranoia inoculates us against complacency.

As Nigel Bogle was wont to warn, even in the good years, ‘We’re three phone calls away from disaster.’

So don’t get sucked in. Better to keep a cool head than to drink the Kool-Aid. Let’s maintain our distance, keep a wary eye. And like Vallotton, let’s give ourselves the benefit of the doubt.

'She had a place in his life.

He never made her think twice.

As he rises to her apology,

Anybody else would surely know

He's watching her go.

But what a fool believes, he sees.’

The Doobie Brothers, ‘What a Fool Believes’ (M McDonald, K Loggins)

This piece first appeared on Jim Carroll's Blog here